Farmers have good reason to be bullish on corn and soybean crops they’re harvesting this fall. Other markets foundered on fears of rising interest rates, inflation, recession, and heated rhetoric from Russia. Grain futures battled against the tide, supported by forecasts of lower U.S. production that may be getting even smaller.

Maintaining most of the gains off summer lows was an achievement in the face of all the red ink that flowed elsewhere. The stock market and crude oil, to name two, honed in on their lowest prices of the year after the Federal Reserve Sept. 21 raised its benchmark short-term interest rate by another three-quarters of 1% and signaled more pain ahead for borrowers.

Central banks around the world are following the Fed’s lead, but few other economies have the strength to match the moves signaled by Jay Powell and Co. in Washington. In all, the Fed so far this year raised its target by 3%, and forecasts from participants at last week’s two-day meeting on monetary policy indicated additional hikes of up to nearly 2% may be needed before rates peak next year. That would bring the target for Federal Funds to 4.87% according to high end of the dot plots released as part of the quarterly summary of economic projections.

Wall Street angst

For all the angst on Wall Street, the cost of money is still a whole lot cheaper than it’s been historically, including when an inflation-weary Fed moved aggressively during the 1980s. After down-playing rising prices as “transitory,” officials now hope a series of fast, big rate hikes will unwind the spiral.

Congress gave the central bank a two-fold mandate: maximum employment and stable prices. With unemployment still below 4%, the Fed is betting any recession it triggers won’t be severe enough to send joblessness to unacceptably higher levels, though no one is sure what that pain threshold actually is these days.

Dollar hits 20-year high

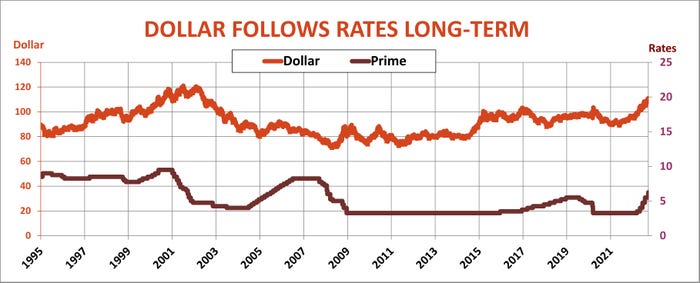

The bearish reaction by the S&P was predictable – “Don’t fight the Fed” is a prime investing rule. And the fallout from higher rates was also in line with past trends. The dollar index showed the greenback strengthening against other widely traded currencies to its highest level in more than 20 years.

Some of the dollar move was a flight to safety. While the U.S. economy teeters, much of the world is already falling off the cliff, making the buck the best of a bad lot globally.

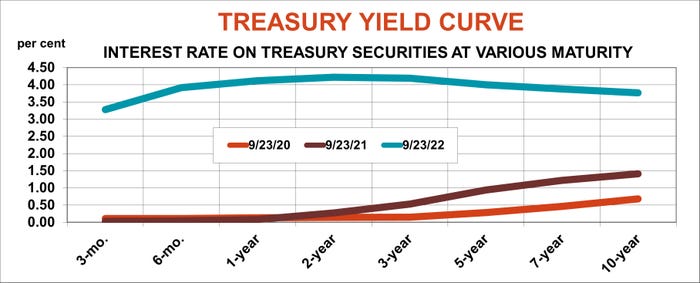

Investors also value currencies backed by governments offering a higher safe return. Yields on Two-Year Treasuries topping 4% don’t yet provide a real yield after inflation, but they’re closer to that goal than in other advanced industrial economies.

Rates are considerably higher in emerging market countries where inflation rages, and the Fed’s latest move prompted comparisons to the 1990s panic in foreign exchange trading that rocked around the world from Mexico to Asia to Russia and Brazil.

Farm fallout

The fallout for U.S. farmers is multi-dimensional. First, importing countries have less to spend on food subsidies. Two decades ago that forced customer to buy less or switch to cheaper alternative livestock rations sourced closer to home. The shock from the crisis decimated the U.S. share of world exports that has yet to recover.

The stronger greenback also tends to pressure dollar-denominated commodities, one reason for crude oil’s decline. But commodities valued in local currencies move in the other direction, providing their farmers with incentives to expand.

Brazil’s central bank pushed its benchmark interest rate to 13.75% to combat double-digit inflation, sending the Real currency toward the bottom of its long-term range, where it’s been stuck since the pandemic began. Farmers there who price their crop in dollars receive more reais in return.

Brazilian soybeans priced in dollars today are about the same as in 2014. But the value of the real against the dollar weakened by some 55%, giving farmers more than double the reais after conversions.

More bearish fallout from the currency crisis came from Brazil’s big neighbor Argentina. Fears of a depreciating currency can convince farmers to hoard crops as an inflation hedge, a time-honored practice in Argentina where inflation runs at an unbelievable 75%. The government there needs taxes on soy product exports for crucial revenues, so it recently gave farmers some protection with a pesos-for-dollars exchange rate more than 40% above the official conversion, prompting producers to finally sell.

Higher storage costs

Rising rates have impacts on the other side of the income statement for growers, and perhaps their balance sheets, too.

Higher rates increase expenses, of course, but they also impact management decisions by raising opportunity costs – that is, the break-even for a choice compared to doing nothing. The first crossroads for most producers is happening right now.

Interest costs are key factor in deciding whether to sell grain off the combine or put it in storage. Interest is still due on loans that aren’t paid off with proceeds from harvest sales, and even debt-free farmers must consider storing cash from grain movement in a CD or T-Bill instead. This wasn’t as significant when interest rates were lower. But CCC loan rates follow the Fed, and average commercial operating rates should approach 7% in October – with more hikes on the way.

As a results, growers face monthly interest costs of 4 cents a bushel on corn and nearly 9 cents on soybeans, not to mention higher energy bills for drying and aerating bins.

Storage could still be profitable if prices rally enough. But futures don’t provide much incentive in the way of carry for hedgers trying to benefit from basis appreciation alone. There’s little to no carry on the corn board, while soybeans are paying barely a penny a month.

Farmland could also be less attractive for outside investors – though farmers looking to add to their holdings might welcome less competition from suits at auctions. The capitalized value of farmland is one metric valued by Wall Street, comparing how income from cash rents compares to so-called safe investments like the 10-Year Treasury Note.

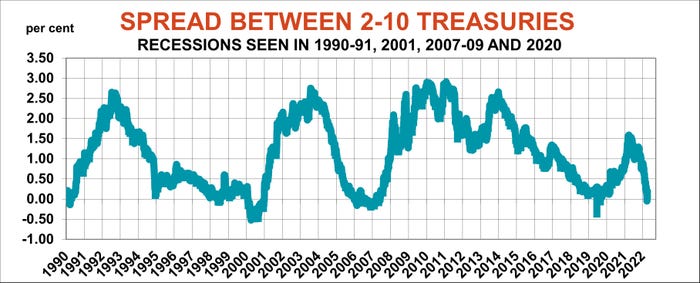

Those longer-term rates haven’t gone up as much as the short durations – the “inverted” yield curve is a classic warning sign of recession. But the 10-year yield still reached 3.5% last week, more than double year-ago levels, slashing the “cap value” of the asset.

Food accounted for 13.5% of total consumer inflation this summer, and defeating inflation could hurt grain prices if it removes incentives for funds to own commodities as a hedge. That doesn’t preclude rallies but reflects headwinds from financial markets growers must navigate in the months ahead.

Cash is king

The good news: If you’re a farmer, it’s a great time to have cash. Interest rates don’t offer inflation-adjusted returns, but they’re closer than they’ve been in years.

Online banks are offering up to 2.75% on savings, so check your own bank to see their rates. One-year CD’s are bringing up to 3%. You can purchase these directly or through a broker, though that ties up the money.

Your best bet for safety, accessibility and yield may be to go directly into the U.S. Treasury market. If you buy from a broker or bank commissions vary. Many brokers now charge no commissions. If your institution still charges, you can buy free from the government’s Treasury Direct. If you want maximum accessibility to funds, go with the 30-day T-Bill, yielding 3.25% now. This rate will vary, but should stay elevated for the next year or two. You simply roll the funds over in the Treasury Direct account until you need them.

If you won’t need some of the funds in short term, you can go out to the 1-Year Treasury, which is above 4%. But if you need to sell this, the value of the principal may go down if rates keep rising.

Another alternative is to ladder the investments, buying different durations, though again you have some principal risk.

Use caution with ETFs, index funds or mutual funds. The prices of these will go down if rates keep rising as expected, exposing principal to risk when the instruments are sold. Individual corporate bonds have credit risk from a poor economy, in addition to interest rate sensitivity, making them a less desirable choice.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like