This is the time of year people start wondering how cold and wet winter will be.

Well, if you believe the Old Farmer's Almanac, winter will be milder and drier than normal, but there will be periods of freezing cold with above-normal snowfall. The coldest periods will be in early to mid- and mid- to late January, and early February. The snowiest periods will be in mid- to late November, mid-January, and early February.

University of Missouri Extension livestock specialist Gene Schmitz does not claim to predict the weather. All he knows is that during the winter months there will be at least a few days or even weeks of cold, wet weather, and cattle producers need to be prepared.

Many beef producers realize that when the weather gets colder, their cows need more energy to maintain body condition. Schmitz says cattle producers need to understand when cows start experiencing cold stress to determine how much more energy or feed they are going to need during the winter months.

How cold is cold?

Low critical temperatures or the temperature when cattle feel cold stress is based on thickness and wetness of the hair coat, Schmitz explains. Wind speed and air temperature play into the calculation of real temperature.

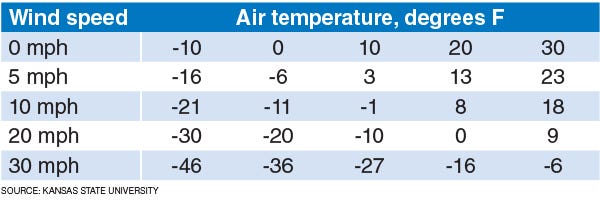

The table from Kansas State University on wind speed shows the windchill index for varying combinations of wind and temperature.

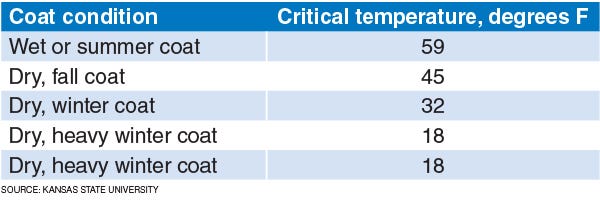

The next table on coat condition shows when cattle feel cold stress depending on their hair coat. According to the data, a cow with a dry winter hair coat feels cold stress at about 32 degrees F and a cow with a wet winter hair coat feels cold stress at 59 degrees.

Determining energy needs

According to Schmitz, for each degree of cold stress, the cows’ energy requirements increase by 1%. "A cow on a rainy 40-degree day will have the same cold stress, and thus the same increased energy requirement, as a cow on a dry, sunny 13-degree day," he explains.

If the cow has a dry winter coat and is exposed to an effective temperature of 10 degrees, her energy requirements increase by 20%. Schmitz calculates the effective temperature by the actual air temperature minus the wind speed. For instance, an effective temperature of 10 degrees is when there is a 30-degree air temperature and a 20-mph wind speed.

How to feed in cold conditions

To deal with the cold stress, the cow's metabolic rate increases, which increases the need for dietary energy, so the cow tries to eat more feed. The general rule of thumb is to increase winter ration energy 1% for each degree (F) below the lower critical temperature. "The cow exposed to an effective temperature of 10 degrees will need to consume about 4 pounds more hay or 2.5 pounds more grain in order to meet this increased energy demand," Schmitz explains. However, he adds the cow may or may not be able to increase intake that much if the hay is poor quality.

The only way to help boost intake if feeding low-energy hay is to supplement with high-energy feed. He says farmers may want to add grain, grain byproducts, or higher-quality haylage or silage to the feeding ration.

Beef farmers must take the time to understand how cold, wet weather can affect cow stress, and then adjust feeding regimens to help cows maintain body condition during the long winter months.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like