When Kevin Bradley brings a potted plant into his home, his wife just shakes her head. It is not often that a Palmer amaranth weed is viewed as a houseplant. But when the University of Missouri weed scientist travels the countryside explaining the state's No. 1 weed to watch, well, he needs a living example.

Bradley takes his "traveling partner" to educational meetings so farmers can see what Palmer amaranth looks like. The weed is a summer annual that commonly reaches heights of 6 to 8 feet, but it can reach 10 feet or more. It looks a lot like its distant cousin waterhemp. However, there are a few distinct differences.

Identifying Palmer amaranth

Palmer has a poinsettia-type leaf arrangement, Bradley says. The green leaves are smooth and arranged in an alternate pattern that grows symmetrically around the stem. The leaves are oval- to diamond-shaped. Overall, Palmer amaranth is larger, thicker and has more spines than waterhemp.

In a field, mature Palmer plants will tower over waterhemp. Its seed head is very different. A Palmer plant has a spike three-quarters of an inch to an inch in diameter, and female spikes can grow as tall as 3 feet. It is twice as competitive as waterhemp and can produce as many as 1 million seeds per plant.

Season-long competition by Palmer amaranth at 2.5 plants per foot of row can reduce soybean yield by as much as 79%, according to Bradley.

The problem is, the weed continues to spread throughout the state.

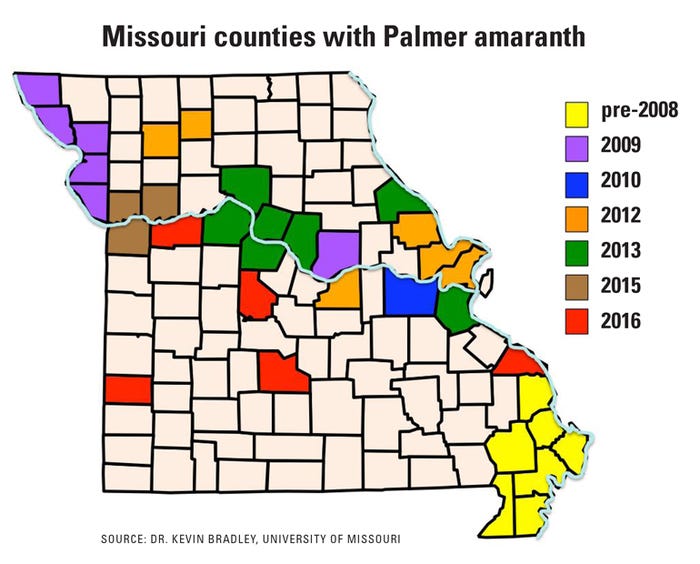

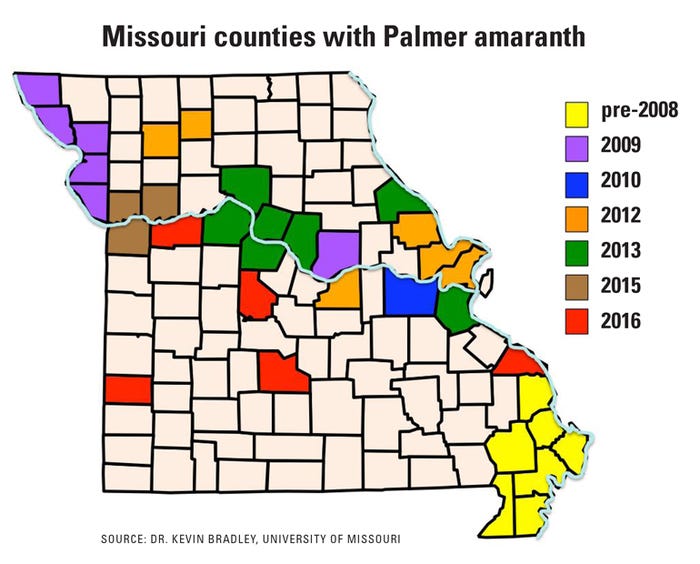

"It has always been a Bootheel weed," Bradley explains. Palmer amaranth was likely in the southeastern region of the state back in the 1990s. Bradley started tracking its movement in 2008, and he found that the weed continued to spread north throughout Missouri — invading five more counties each year.

Palmer amaranth has been invading counties across Missouri for the past 10 years. MU weed scientist Kevin Bradley put together a map to show its progression over the years.

How it spreads

Bradley says that often farmers do not realize they are spreading Palmer amaranth seed.

He knows of seed carried in on equipment and hay purchased from Southern states. MU research finds that Palmer seeds also travel with the help of waterfowl. And more recently, pollinator mixes are including Palmer amaranth weed seed in bags.

Bradley says farmers should be cautious when purchasing equipment or hay out of states known to have high instances of Palmer amaranth — like Arkansas, Tennessee or Kansas. The key is to remain vigilant in protecting fields from this weed. However, if it sprouts up this spring, eradication is critical.

New control measures on horizon

Farmers should consider cultural practices for Palmer amaranth control like narrow row spacing of crops, cover crops and harvest weed seed management.

Bradley says the next big thing in weed management will likely be harvest weed seed management. It started a decade ago in Australia. The country had a ryegrass resistant to all herbicides on the continent.

An Australian farmer, Ray Harrington, developed a machine known as the Harrington Seed Destructor (HSD) that grinds small weed seeds, rendering them unable to germinate. It is a pull-behind piece of equipment with a high price tag — around $100,000. U.S. universities are looking at the machine to see if it is practical for farmers. Agriculture equipment companies are also looking at ways to incorporate similar systems inside combines.

Bradley conducted his own experiment for mechanical weed control last year. He and his graduate students fashioned a metal chute that discharged seed and residue from the combine into windrows. It cost a mere $50, but it worked. At harvest, the seed and chaff formed a perfect line. Students then burned the windrow containing weed seed with a propane torch in an attempt to destroy the seed.

After a Twitter video post of the event, farmers began calling. Bradley says that while it seemed to work in the field, more research and data need to be compiled before recommending the practice. However, he says these types of mechanical options hold promise for the future of weed control.

In the meantime, Bradley recommends that farmers use multiple modes of herbicides to destroy Palmer amaranth in fields. Use full rates on soybean. Overlap residual herbicides. The herbicide glufosinate and the LibertyLink soybean system still work.

Bradley's houseplant serves as a visual reminder of Palmer amaranth's threat to Missouri fields. Farmers must know how to identify and treat this resilient weed in order to keep it from blanketing the state.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like