November 4, 2019

The future of on-farm autonomy continues to evolve. The very idea of driverless machines roving across farmland is no longer just a romantic notion of science fiction writers. But what will those machines of the future look like? And how will they do their jobs?

At the University of Georgia Tifton campus, in a nondescript green steel building, the future is happening. Glen Rains, who works in the Department of Entomology on the campus but focuses on a range of ag engineering projects, is heading up the Multifunction Intelligent Vehicle Development Program, and Farm Progress got a look at an early proof-of-concept vehicle.

The skeletal machine, which is in essence a carrier for sensors and tools, is built on a simple design that Rains explains is designed for the smaller farmer. “Equipment has gotten so large, our approach was to look at this from the perspective of a midsize farmer,” he says. “We have mounted a cotton harvest unit on the machine that picks cotton one plant at a time.”

The project, which is funded by Cotton Incorporated and the Georgia Peanut Commission, shows a kind of cotton picker unfamiliar to most. The small attachment on the robot’s arm can move from plant to plant, grab the bolls (not with fingers or spindles, but with small tines) and vacuum them into a container.

ON ITS OWN: This is the UGA proof-of-concept vehicle for a field robot that could eventually do many different chores, including weed and pest control, and seeding.

“We can have two arms on the machine,” Rains explains. But Rains is in this for more than harvesting cotton. The Peanut Commission support shows that there are commonalities for this multifunction machine.

“Yes, we can use the machine for weeding, scouting, spot spraying and planting,” Rains says, envisioning a kind of autonomous tool carrier that can take on specific tasks as needed. He notes that with advanced artificial intelligence, spot spraying just weeds in the growing crop would be part of the chore list for this machine.

Proof of concept

Looking at the test machine, which is still in the early development stage, a visitor sees a tall, gangly Erector-Set machine. Powered by a Kohler engine, the robot has an operator seat since it’s important to control the machine during transport. Yet the machine is mounted with a range of sensors, and a smart arm that can raise a tool up or down and move it from right to left.

“We went with the more simple X,Y configuration of the arm, because it would be simpler to maintain,” Rains says. “Farmers like to be able to fix their machines.”

The program, which Rains originally estimated could take 10 years, has been underway for two. There are a lot of moving parts for a program like this. And the final concept looks much different than the test-bed vehicle. He adds that as more people see the proof-of-concept machine, there may be interest in greater investment or companies taking the tech on as their own project.

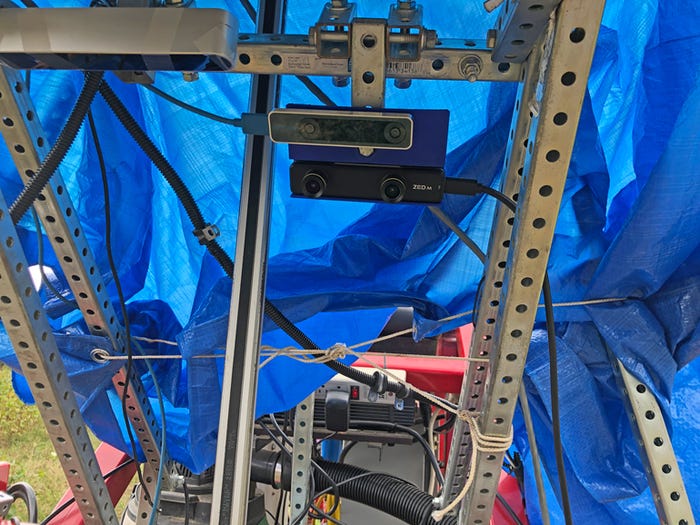

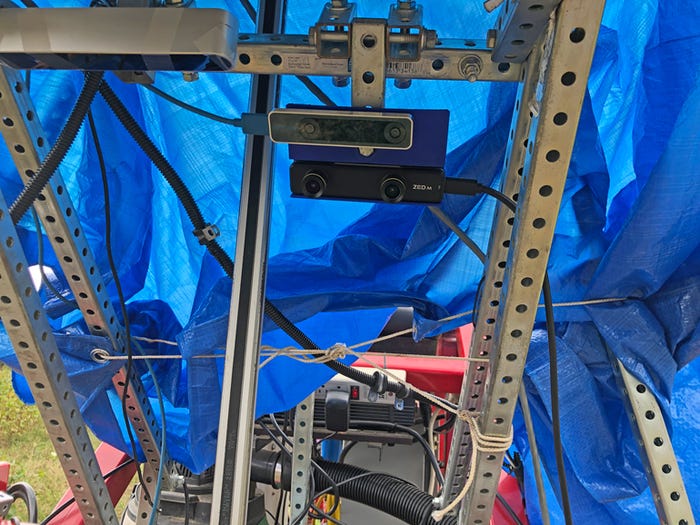

SENSORS AT WORK: The sensors shown here help the UGA Multifunction Intelligent Vehicle find its way and track the row. They will eventually be used for other tasks.

Rains shared that the next version of the machine will be much smaller, and he showed the early-build version. “It will be solar-powered, and you would put more than one in a field,” he says. “It would have multiple batteries, and perhaps a charging station in the field to plug it in when it has some downtime.”

The idea of autonomous machines — driven these days as much by technology as the changing farm labor market — is nearing a key development time. “I think we’re at a crossroads now, where sensing technology and processing speeds and machine learning have gotten us to a point where we can actually make some practical devices for farmers,” he says.

The smaller robot that would become the eventual tool would be designed to work in a field with multiple machines. This “swarm” concept offers a range of benefits, from full-time weed and pest control to field scouting, and is not crop specific.

Rains continues his work with graduate students Kade Fue, Canicius Mwitta and undergraduate student Logan Moran. Mwitta is working on using the platform to control weeds in cotton and peanuts; Moran is a student attending Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Tifton.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like