In its 40-year history, Husker Harvest Days has had a tremendous impact on production agriculture not only in Nebraska, but across the Great Plains and U.S. Thousands of irrigators, dryland farmers, ranchers, conservationists and researchers come to HHD each year to learn about the latest equipment, technology, management practices and issues affecting agriculture. Some people have been a part of HHD since the very beginning. Others have introduced new ideas to the show that have since become a cornerstone to the event. Here's a look at what five remember from the last 40 years at HHD:

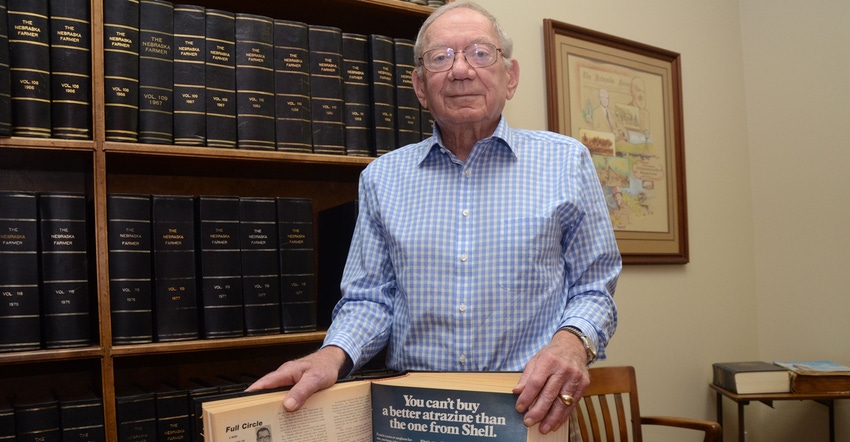

Don McCabe

It was a cool, misty day when preparation began at what would become the Husker Harvest Days show site in October 1977. Don McCabe had just joined Nebraska Farmer in the first month of his 37-year career. "I had just joined the staff in October 1977. It was my second trip out of the office to go out to the show site," says McCabe, who brought along a Bronica S camera from the 1960s to photograph the occasion. "To the naked eye, the show site was a flat piece of ground, but they had to spend a day tilling the soil to convert it from pasture to cropland, and brought out a laser-leveling machine to level it for gravity irrigation, which was still the prominent irrigation method at the time," McCabe recalls. "At the end of the day, they lined up the tractors they had brought out that day for a photo."

In those 37 years, McCabe never missed a show. That first year, McCabe recalls going airborne to cover the show — but not in an airplane. This year, he was in the back seat of a two-seater powered parachute, leaving him unhindered to take aerial photos, which presented its own set of challenges.

"We took it to an alfalfa field and stretched out the parachute behind us," McCabe says. "We ran up the alfalfa field until the parachute billowed, and it picked us up. When I shot a roll of film, I had to make sure I held on to it and put it in my pocket. The pilot said, 'Don't let that canister hit the fan.' You don't have a window or frame in the way. Most of the time, it was a good medium to take photos."

Through the years, one of the highlights at HHD has been seeing the evolution of irrigation systems, says McCabe. In the beginning the show site featured a combination of gravity irrigation and center pivots.

"For a couple years, the show site had a lateral-move system. In one case, it was an open ditch, where the lateral had to drag the hose," McCabe says. "Another case was underground piping where a pivot would latch on to the riser; it would move along until it latched on to the next riser."

And as one of the largest farm shows in the country, it has been a hot spot for discussing pressing issues surrounding agriculture, from trade to property taxes to farm policy. "One year, in the 2000s when Mike Johanns was the secretary of agriculture, there was a USDA listening session for the farm bill at Husker Harvest Days," McCabe says. "It was a period of low prices, export problems, and it was really well-attended."

Bob Bishop

At the time of the first Husker Harvest Days, Bob Bishop was in charge of editorial and production at Nebraska Farmer. Bishop notes that the idea for a show where farmers and ranchers could witness the latest machinery and technology in action in the field was dreamed up by a group of representatives of the Grand Island Chamber of Commerce — the group that came to be known as the Agricultural Institute of Nebraska (AIN).

But there were challenges in getting the show off the ground. The group negotiated with a lease holder at the Cornhusker Ammunition Plant on a quarter-section to use as the show site. But in those early days, there was little financial backing available to get a farm show started.

"The show site had been leased as pastureland and had to be converted and wells had to be drilled. That was all accomplished with cooperation of exhibitors themselves. Exhibitors were as much a part of the beginning of the show as anyone else," Bishop adds. "We asked many potential exhibitors to contribute equipment and irrigation systems to the show. We used to have to negotiate for fuel for the farming operation itself. Those things were really tough."

However, over the years, HHD's popularity drastically improved, and the show became known as the premier farm show in the world's largest totally irrigated farm show.

Bishop was with Nebraska Farmer for 38 years, first as a field editor, then an associate editor, managing editor, editor and executive editor. He notes over the last 40 years, the show has been a leader in showcasing the latest in ag technology.

"The last few years, GPS equipment, equipment that allows farmers to fine-tune all the procedures they had been doing in the past, horsepower increased and equipment got bigger, better," he says. "We saw Husker Harvest Days as a leader in showing changes through the years — from changes in tillage practices to changes in irrigation technology. And practices are always changing."

But the show site itself saw big changes as well — improvements in infrastructure, drainage and, of course, permanent restrooms. They originally used about 200 portable.

"I always tell people, I was a field editor, managing editor, editor, but what I'll really be remembered for is putting in flush toilets at Husker Harvest Days," Bishop says. "When I started, the first thing I talked to Tom Bud [who was Farm Progress editorial director at the time] about is we need to invest in permanent restrooms."

40 YEARS OLD: Eugene Glock, pictured here with son, Ted, has used this 1978 International 1460 combine for nearly 40 years. "The first time I went through the field I didn't get through a quarter-mile row and dirt flew, and they shut it down and they used a 1-inch cleaning fan shaft. When you ran it up to 1,200 rpms when you had heavy corn, that 1-inch shaft would flex just enough that once in a while the blade would catch something. They came out and replaced it with a 1.25-inch shaft," says Glock. "When we get repairs for it, we have to have the serial number, because it's one of the first ones made."

Eugene Glock

Eugene Glock, who farms near Rising City and was state agriculture representative on U.S. Sen. Bob Kerrey's staff for 12 years, has been involved with Husker Harvest Days since day one.

"The goal they always had was to inform farmers so they could pick the product that would do the best job for them. The way I see it, that's what is done today," says Glock.

Eugene has been going to HHD since 1978, sometimes bringing his wife, Melba, and always bringing his son, Ted. Later on, his grandson and Ted’s son, Marshall, would join them as well. "Ted had two reasons for going to Husker Harvest Days, and one of them has not changed," says Glock. "Marshall was like Ted: His first goal was to find something new to eat; his second was finding a new pickup."

In July 1978, husband and wife and internationally-known photographers Nicholas and Wendy Boothman spent a week on Glock's farm to prepare a 30-minute slideshow titled, "The Farm," to be displayed at the upcoming show.

"Bob Bishop wanted them to follow a farm family for a week to show people other parts of the country that were there at HHD what a week in the life on the farm was like. They took pictures of us irrigating, and they took pictures of us riding horses and moving cattle. They took pictures like that of our family at meal time," Glock says. "My daughter [Beverly] and her husband [Tom Goodwin] got married at the end of September 1978. Nick and Wendy found out there would be a wedding, and lo and behold, they came back for the wedding and took all the wedding pictures."

Of course, when it comes to machinery and technology, things have changed drastically through the years at HHD. Back in the early 1980s, Glock volunteered the use of his International soybean drill to demonstrate 7.5-inch-row soybeans at the show site. Soybeans can still be found at the show site, but drilled soybeans have mostly fallen out of favor with farmers in the Cornhusker State — a space largely filled by 30- or 15-inch planters.

"It was one of the first soybean drills International came out with. Because I gravity-irrigated, I had our local blacksmith build a corrugator for gravity irrigation when you can't make furrows in 7.5-inch rows," Glock says. "He made a rig that had a big V-shaped piece of steel curve in the front, and you mount it in the back of the drill, and it had hydraulic pressure on it. It made a groove in the field every 36 inches to help direct the water down the field."

Joe Jeffrey

Dr. Joe Jeffrey, nationally known livestock veterinarian from Lexington, has been managing the cattle handling demonstrations at Husker Harvest Days for nearly 30 years. The idea for the first cattle handling demonstrations was borne from a discussion between Tim Talbott with Big Valley, and Terry Butzirus, regional sales manager at Farm Progress, while at the National Western Stock Show in Denver. Talbott and Butzirus brought the idea to Jeffrey and John Kearney, who was also with Big Valley (eventually with Behlen).

"Cattle handling got started because vendors were having trouble getting people to stop and look at their chutes," says Jeffrey. "We said, 'Maybe we ought to work some cattle. What if we lined up different chutes and ran cattle through them and see if people would watch?'"

On the first year of cattle demonstrations, three companies exhibited their chutes — Big Valley, Palco and Linn Enterprises, notes Jeffrey. Over the years, a number of new companies and new chutes have been added, and in the last 30 years, Jeffrey has seen several different kinds of livestock run through the chutes, including pigs, sheep and longhorn steers.

And in those early days, the cattle were on the wilder side. "On the first day, we had an 800-pound steer in a chute, put the head stabilizer on, and he went down and started choking," Jeffrey says. "John Kearney and Van Neidig [of Lakeside Manufacturing] found the right levers and got the calf out. He was just a little wheezy, but he started to come around, and when he decided to get up, he got under the head stabilizer and pushed the chute over. He cleaned out that area."

Over the years, cattle handling demonstrations have moved from a tent to a permanent Livestock Industries Building. Now, the demonstrations are a well-oiled machine, running around 150 cattle through chutes each year, and allowing visitors to compare chutes side by side.

And Jeffrey notes cattle chutes have dramatically improved in terms of safety and animal welfare. "When I got out of vet college in 1960, chutes would always have a head bar in front at the head gate to bring down to hold their head. If the animal would slip and go down on their knees, they were choked. Thank goodness that's a thing of the past," says Jeffrey. "Safety wise, these chutes now have a brisket bar that keeps the animal and their head up so they keep their head in the gate comfortably."

Over the years, cattle handling demonstrations have been visited by a number of politicians from Nebraska.

"We've had some dignitaries like [then Gov.] Mike Johanns, [Gov.] Kay Orr. We've had some pretty important people come in," Jeffrey adds.

Wayne Venter

Wayne Venter was one of Husker Harvest Days' earliest show managers, helping coordinate the show from 1978 to 1991, and managing the show from 1983 to 1991.

Venter went later on to manage the Lancaster Event Center in Lincoln, the Big Iron Farm Show in Fargo, N.D., and the Platte County Fair in Columbus. "All the jobs I got after were because of Husker," he says. "But none of them were as fun as Husker."

In the early days of the show, advertisement sales reps helped out in laying the groundwork for the show, Venter says. This includes setting stakes and cable to survey the site, weed eating and mowing, setting up telephone poles and maintaining the site. "You had to know how to be an electrician, a plumber and mechanic," Venter says. "I ran everything but a combine and a planter."

Venter notes one year in the early 1980s, the show site received 11 inches of rain. "There was so much water you had to put pallets down so people could walk into exhibits," he says. "That was the only time we canceled a show on opening day." So, Nebraska Farmer staff worked with show crews to pump water out of the show site.

However, there were also financial challenges in those early days. The show negotiated trade-out agreements with vendors for equipment, fuel, fertilizer and seed.

In the first couple years, Venter notes it was difficult to persuade advertisers — even those that had already qualified for exhibit space — to come to a new farm show.

"It's like they said we don't need another farm show, because there were quite a few," he says. "They just didn't understand what the potential was. They knew farm progress was a success and knew that another farm show to be successful really had to have field demonstrations. That was the key to get it going. We were guaranteed field demos, excluding bad weather, because it was irrigated."

"By 1980, we knew this show was going to work. People will come," Venter says. "There was a need in Nebraska, and I know the editors and advertisers were all on the same page with the same goal — to help producers farm better and improve their bottom line. That was the big push."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like