June 21, 2017

Think Different

Start from square one evaluating current aggregate levels.

· Compare results from fields with different cropping patterns and tillage.

· Work with a neighbor to compare aggregates under different practices.

· Calibrate your results against similar soils in your region.

------------

George Holsapple is seeing his soils improve as never before. The conventional tiller turned vertical tiller from Jewett, Ill., adopted cover crops about four years ago and has noted visual improvement in tilth and water infiltration in his fields of corn, soybeans and cover crops for seed that he farms with his wife Janice and son Thad.

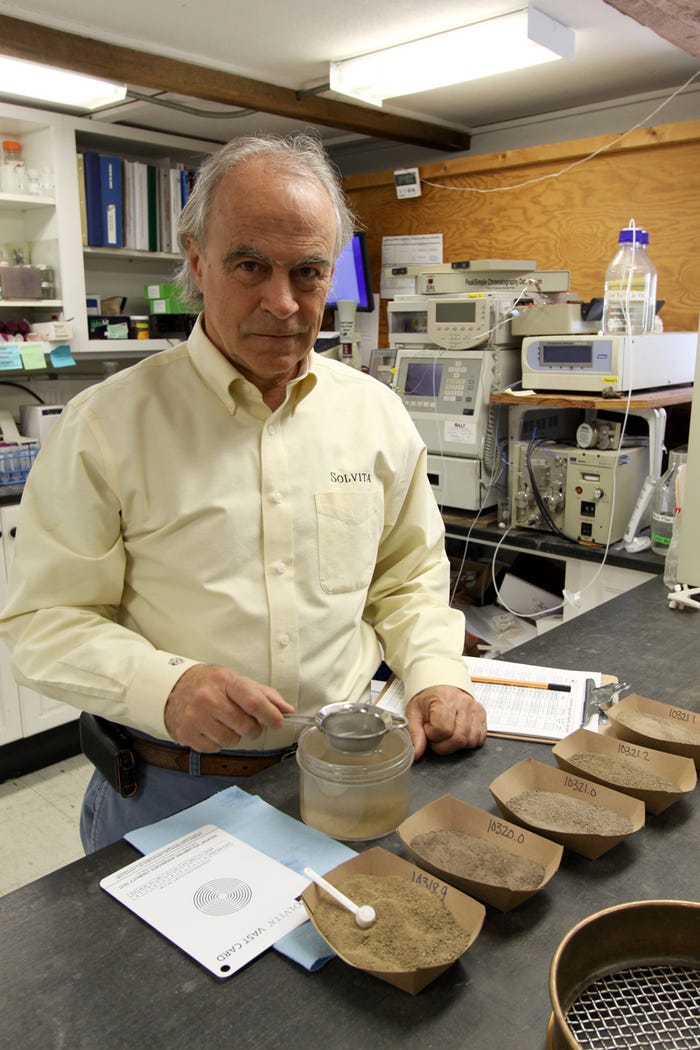

While these are indicators of improved soil health and soil aggregation, Holsapple had no way to verify the soil texture improvements. That has changed with the introduction of the Solvita Volumetric Aggregate Stability Test (VAST) from Woods End Laboratories. VAST measures water-stable soil aggregates. These aggregates are what provide porosity and structure for air and water infiltration. That is vital to Holsapple's goals.

Seeking no run-off

"Our goal is to have no run-off from our fields," says Holsapple. "I know we are improving what we are doing, but I wanted a test to measure it from year to year."

In fact, quantitative tests to evaluate soil aggregation have been in place since the 1970s and are offered by several labs, including the Cornell University soil lab. However, most were wet dip methods that weigh the samples before and after for evaluation. They are time consuming and highly technical, which is costly, notes Dr. Will Brinton, Woods End Laboratories.

As an on-site alternative, Ray Archuletta, conservation agronomist with the NRCS National Soil Health and Sustainability Team, developed a simple test where clods of soil from different fields are dropped in jars of water and the rate of fractionation is compared. However, it is not a quantitative test. The NRCS rainfall simulators provid the closest thing to a quantitative evaluation, but only a handful exist across the country and are largely used for field days.

"Soil structure has been a hot topic for the past decade, along with the growth in reduced tillage and efforts to reduce runoff and soil loss," says Brinton. "Farmers like Holsapple were looking for an affordable way to measure and compare aggregation between fields and from year to year to justify management changes. Soil labs needed a way to provide it."

Brinton dusted off a structural geometry model he had developed as part of a research project in the 1980s. At the time, a fellow researcher was studying the impact of crop rotation and was looking for a rapid test for aggregation. Brinton's test uses a volumetric approach, measuring the change in volume as aggregation is destroyed.

"Imagine compressing a loaf of bread," says Brinton. "It might go from five inches in height to 1/2 inch. With our test, soil may go from 50 cubic centimeters to five.Testing by weight misses the point. When you destroy the aggregation, you have the same weight of soil, but the volume decreases substantially."

Corn+Soybean Digest submitted a soil sample from a field that had been in alfalfa for a year after several decades of continuous corn. According to VAST, 37% of the sample volume was held in stable aggregate form, moderately high aggregate stability, according to Brinton.

Need baseline test

While the information is interesting and provides a baseline, unlike with organic matter, there is no way to go back in time to evaluate the aggregate level prior to adopting alfalfa. "A farmer may have organic matter data going back 20 to 30 years or longer," says Brinton. "With soil aggregates, you are starting at square one."

Holsapple is fine with starting at square one, although he started as a Beta tester for Woods End three years ago. Every year since he has been able to evaluate the impact of his one pass vertical tillage and ever-changing cover crop program. Holsapple commonly mixes from six to 10 different cover crops in a field. Rather than emphasize biomass, he is working on weed and erosion control, as well as drainage and pest control. He uses barley for drainage, vetch to open up the soil and three different kinds of oats for overall soil health and some nematode control.

"VAST shows us our soils are improving every year," he says. "We knew we had benefitted from our diverse cover crops, but now we can really learn what the mixes are doing."

Several soil labs, including Brookside Labs in Ohio, A&L Canada and NextLevel AG in South Dakota, are adding Solvita VAST to available tests. Brinton is recommending a $12 to $15 charge per sample; however, some labs plan to package it with other tests. He sees it as the missing (physical) leg in in a three-legged stool of currently available chemical and respiration-based soil health tests.

A new standard coming?

"Fast forward five years, and I would hope tests like ours would be standard in soil labs," says Brinton. "If this is done well, it can take farmers to another level of soil health."

He acknowledges doing it well means calibrating results to the soil type. A 25% result in eastern sandy soils is good, while a starting point of 40% in clay soils of the Midwest is not unreasonable. The sample submitted by Corn & Soybean Digest was a silt-loam. Generally, it would be expected to have good drainage and air and water infiltration. Brinton suggests comparing it to the same soil type in a nearby field farmed with different practices.

Holsapple is comfortable with year-to-year evaluations of his own fields. "We have creek bottoms that are sand, and they are improving as well," he says. "We are seeing less cocklebur and waterhemp as the soil life chews up the residue, including weed seeds. It is holding the soil together, and we don't see near the erosion as fields around us."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like