Flowing grain inside a grain bin can kill — quickly.

5 seconds: The time it takes from when a grain auger is turned on to when a farmer standing on top sinks and becomes trapped.

22 seconds: Grain completely covers the farmer.

60 seconds: The grain suffocates the farmer.

Suffocation is the most common cause of death related to grain bins.

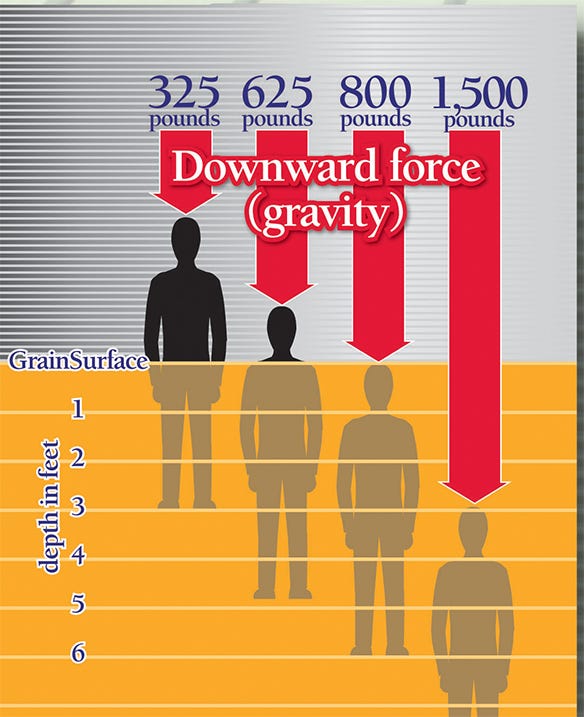

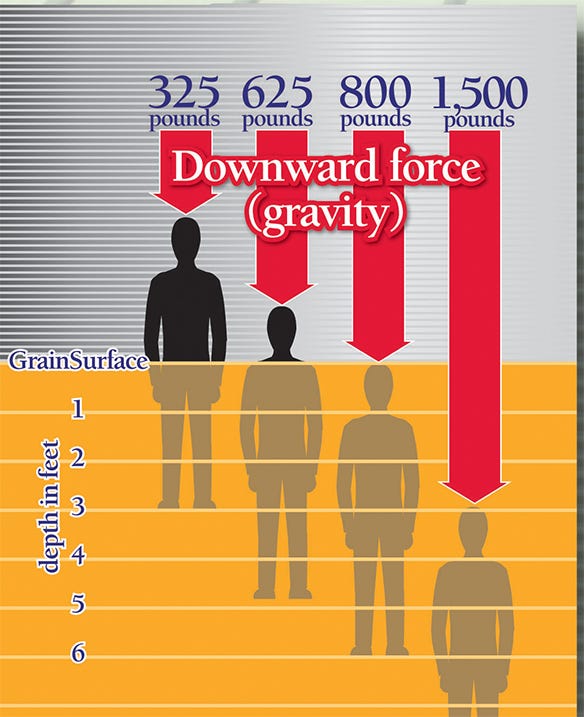

HEAVY LIFTING: It takes more than 325 pounds of force to extract a 6-foot-tall, 165-pound person from just 3 feet of grain in a corn bin. It takes more than 1,500 pounds of force to extract a 6-foot-tall, 165-pound person if the person’s head is 3 feet down (meaning the feet are 9 feet down) in the grain bin.

There were 60 confirmed grain bin entrapments and incidents in confined spaces on U.S. farms in 2016, according to Purdue University data. That’s a 27% increase from 2015, and Purdue estimates that an additional 30% of cases go unreported each year.

Due to the number of fatalities and injuries attributed to engulfment and entrapments in grain bins on family farms and at commercial grain handling facilities, the National Grain and Feed Association (NGFA) is working with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the University of Missouri Extension to host an awareness week to remind both employers and employees about common entrapment hazards, according to Jess McCluer, NGFA vice president of safety and regulatory affairs.

The NGFA-OSHA National Alliance, in collaboration with the American Feed Industry Association and the Grain Elevator and Processing Society, created the Stand-Up for Grain Engulfment Prevention Week to promote grain bin safety on farms and at commercial grain handling facilities. This year’s event, held this week, April 9-13, will help raise awareness about grain bin dangers, provide education and share safety best practices.

How accidents happen

Typically, farmers check and empty bins in early spring as they prepare for a new crop.

When grain moisture content is high they check grain frequently, looking for crusting, spoilage and other issues.

DEMONSTRATING DANGER: A University of Missouri Extension exhibit, shown here at the 2013 Missouri State Fair, illustrates how difficult it is to free someone who is trapped in a grain bin. A doll placed on top of the grain in the bin shows how quickly a farmworker sinks into the grain and is covered.

Farmworkers entering bins can become engulfed if they stand on moving or flowing grain. The grain acts as quicksand, pulling workers into the grain, often burying and suffocating them.

3 safety steps

MU Extension safety and health specialist Karen Funkenbusch recommends three ways farmers and their employees can remain safe around grain bins:

1. Have a “zero-entry” mentality when it comes to grain bins. If you must enter a bin, do not go alone, and use proper equipment such as safety harnesses.

2. Use a lockout-tagout kit to ensure that equipment, such as augers, does not have power. Kits cost $100 to $1,000. The expense is small compared to the cost of lost lives, Funkenbusch says.

3. Run ventilation equipment before entering a bin to remove toxic fumes.

Funkenbusch says MU is working with OSHA this week by providing interactive displays, like a small-scale grain bin simulating the strength needed to pull someone out after being engulfed by grain, to help users understand ways to handle grain safely.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like