November 16, 2016

Leonard Payne and Hayward Reece grew up in farm families in the early 1900s. At the time this was a pretty solid predictor they themselves would end up as farmers. Then they fought in World War II.

They ended up as prisoners of war. They were among more than two dozen servicemen from Gilmer County who were held in Nazi work camps, where among other things starvation nearly did the two of them in.

Following the astonishing recovery Payne and Reece made, it is little wonder that they wound up feeding others. Family, neighbors, whoever happened to be driving by, it didn't matter. Their apples nourished bodies and fed souls.

Both have since passed away - Payne in 1976 and Reece in 2006 - but the practice of feeding others is their legacy.

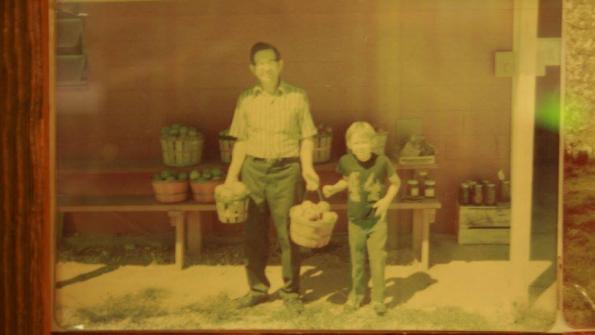

Payne, who grew up in Fannin County, started what is now R&A Orchards in Ellijay, run by his son-in-law Roger Futch, his wife Ann and their son Andy. Reece, whose daughter Janice Hale runs Hillcrest Orchards, also in Ellijay, grew up in Gilmer County, respectively, where the bulk of Georgia's present-day commercial apple production takes place.

Left for dead

Leonard Payne

In September 1944 Payne, then age 22, was driving with an officer near the Rhine River when they encountered German troops. Trying to escape capture, Payne backed up the jeep he was driving and struck a land mine. The explosion flipped the jeep, killing the officer he was driving. The Germans began firing on the jeep, which Payne used for cover.

"He said he didn't think they'd ever stop shooting," said his daughter, Ann Payne Futch. "He said the good Lord just told him to keep his head as high as he could under the jeep."

At least one German bullet struck Payne, and he sustained wounds to his left shoulder and his throat, with extensive damage to his voice box.

According to Ann, this took place near a bridge on the Rhine River, and the German soldiers hauled him from there to one of dozens of Nazi POW camps scattered across Germany. Records listed on genealogy search engine MooseRoots.com indicate he was held at Stalag 11B in Fallingbostel, a small town near the North Sea, just east of Bremen in the German state of Prussia.

When Payne arrived at the camp, he was assumed dead by the German soldiers and was placed on a pile of corpses. According to Ann, a French doctor, also imprisoned at the camp, saw Leonard move and asked that he be removed so the doctor could provide care. The Germans agreed to do so but told the doctor no medicine or assistance would be given, since he was likely to die anyway.

Using the shaft of a pen, the doctor performed a tracheotomy on Payne, allowing him to breathe and keeping him alive.

According to MooseRoots, Payne was kept at Fallingbostel at least 239 days. After surviving his injuries, the scarcity of food - and his ongoing difficulty eating because of the wound to his throat - compounded his problems. At one point, Ann said, he crawled toward the camp fence to reach for some wild lettuce that was growing on the other side.

"The German guards were instructed to shoot anyone who touched the fence," Ann said, noting that her father was asked later if he had been concerned about this. "He said, 'Well, I was going to die anyway.'"

Payne and the rest the POWs at Stalag 11B were liberated in April 1945. He was returned to the U.S. and sent to Lawson General Hospital in Atlanta for treatment and recovery. He was honorably discharged in September 1945, having been awarded the combat infantry badge, three bronze stars and a purple heart.

In 1947 he planted four acres of apple trees. Once they started bearing fruit he sold and delivered them to grocery stores in Calhoun, Dahlonega and other in North Georgia.

According to Ann and her husband, Roger, who worked with Payne as the family's orchard and market expanded, none of this would have taken place if not for the observant eye of that French doctor.

Payne was one of seven brothers to serve in WWII, Ann said, noting that her grandmother received a plaque with all their names on it to commemorate their service.

The injuries Payne suffered left him with minimal use of his left arm. While over time he regained the ability to speak, he could only talk for a few minutes before his voice would diminish to a whisper.

"He didn't talk about it much," Ann said. "You could hardly get anything out of him. Just every once in a while he would say something. That's how I got the stories."

She said the stories only came in pieces.

"If anybody asked him questions he would actually shake, he'd be so nervous. Then he'd just be gone. He'd go out into the woods for a while."

From that initial four acres, R&A Orchards has expanded to 115 acres of apple trees. The R&A market sells apples, baked goods, jams, jellies and vegetables directly to the public. Payne's initial group of trees were standard-root trees planted 30 feet apart, and were much taller and broader than apple trees cultivated today.

Ann said that because of his disability, her father chose apples because a small orchard wouldn't require the same consistent labor as other types of farm operations.

"He was a jack of all trades," Ann said. "He just couldn't hold out. There were a few other orchards around, and he thought he could make a little money with four acres, and it wasn't every day you had to do something."

Hayward Reece

Reece, then 22 years old, was with an infantry unit working its way through northeastern France near the town of Selestat in late November/early December 1944 when an artillery shell exploded near him in a vineyard. He was knocked unconscious and suffered a ruptured eardrum.

Reece's daughter, Janice Hale, provided a first-person account of her father's POW experience which he told her mother, Ellen, who wrote it to have a record for family history.

According to the narrative, Reece was alone when he regained consciousness. He started running in the direction he thought his platoon had gone and rejoined them just outside Selestat. German forces captured Reece's platoon after they arrived in the town.

According to Reece's narrative, which Ellen to save what was left of his unit - 20 men - were moved to Stalag 12A, where he and the other members of his unit were confined with other prisoners from several different nations.

On Dec. 23, an errant Royal Air Force bomb struck the barracks next to the one in which Reece was housed. The explosion killed 65 officers, according to Reece's narrative.

From his narrative: "Most of our windows were blown out and the rest shot out by German guards in the confusion. We were sent out into the night to collect the body parts of our officers blown apart by the explosion. We then spent all of the day before Christmas digging a common grave in the frozen ground for the dead officers."

Reece said he spent 141 days in captivity at three different Nazi work camps. The first relocation from Stalag 12A to Stalag 3B was by rail, with 100 men or more carried in a boxcar intended for 40. The second relocation, to Stalag 3A just south of Berlin, was on foot. The trek took he and his fellow troops past Nazi prison camps where Jews were being cremated.

"These places were truly unholy and filled the heart with fear, repulsion and pity," Reece said in his narrative. "Many Germans in nearby towns said they were not aware of what was being done to the Jews, but I cannot believe that, because the stench was unbearable even a mile away."

Stalag 3A was taken over by Russian forces in April 1945. Hayward and some buddies told a Russian guard they would bring him back a chicken if he'd let them go. They walked off the camp and were picked up by a U.S. Army truck, beginning their journey to Camp Lucky Strike near LeHavre, France.

By this point, Hayward said, he weighed around 85 pounds, and his hunger had lingering effects. For years afterward his stomach would be sore after eating.

Reece was discharged in November 1945, having received the Combat Infantry Badge, World War II Victory Medal, American Campaign Medal, European Campaign Medial and a Purple Heart.

After returning home, he spent time recuperating before enrolling at the University of Georgia, but ongoing health problems cut his education short. He experienced bleeding from his nose and mouth and was found to have a brain tumor, for which he received radiation treatments.

"They said the amount of radiation they [the doctors] gave him should have killed him, but it cured him," Janice Hale said. "He later had a stroke and then just kept having more mini-strokes, and we were told it was probably a result of that radiation - over time those arteries just closed up."

Reece bought a 190-acre farm in eastern Gilmer County that included an existing 15-acre orchard. He raised cattle and worked the orchard, selling apples to passers-by out of the family garage and packing apples to sell wholesale.

"It had that orchard and he just got into it and enjoyed it," Hale said.

In 1979, the Reeces built the Hillcrest Market on Ga. Highway 52 on land a couple of miles away from the family farm. Hale said that in the early 1990s the family began transitioning from wholesale to retail sales directly to consumers. The farm hosts outings for school groups and other organizations for farm tours and educational activities designed to enhance public knowledge of agriculture.

An extensive agritourism venue now, it exists mainly because Reece survived.

"It was really a miracle that he made it," Janice said. "[The orchard] would have never happened. He started it."

You May Also Like