Over the last several years, Mississippi Delta farmers have invested a considerable amount of capital, time, and energy in the purchase, installation, and use of soil moisture sensors — which have primarily been used during the growing season as a part of irrigation scheduling.

But, says Paul Rodrigue, Natural Resources Conservation Service Delta supervisory engineer at Grenada, Miss., winter can provide a good opportunity for producers to become better familiarized with the installation and use of the sensors, as well to gain an understanding of their readings.

“Since 2014, approximately $8.5 million in financial assistance has been provided to NRCS cooperators in the Mississippi Delta to implement conservation practice under the 449 Irrigation Water Management (IWM) program,” he says. “The 449 practice includes financial assistance for developing and maintaining irrigation records as part of an Irrigation Water Management plan, and for the purchase of IWM devices such as soil moisture sensors. Most IWM plans have included the use of soil moisture sensors.”

Most of the funds have been expended through the Mississippi Water Conservation Management Program (MWCMP) that was promoted by the conservation partnership to support the implementation of the findings of the Mississippi State University Delta Research and Extension Center’s Row-crop Irrigation Science and Extension Research (RISER) program.

“The RISER program has demonstrated reduced irrigation water use of up to 25 percent by utilizing computerized poly-pipe hole sizing, surge irrigation, and soil moisture sensors,” Rodrigue says. “Mississippi NRCS anticipates continued funding of the MWCMP in 2018, and practice 449 is available through county funds, so a continued increase in the use of soil moisture sensors is anticipated.”

While RISER has demonstrated the role of soil moisture sensors in irrigation scheduling, users must get acquainted with their installation, use, and understanding of the readings, he says, and winter use of the sensors can provide this learning time.

As you install your sensors, evaluate your soil by depth. Get your hands dirty! And look for restrictive layers (e.g., plow pans).

“The sensors can be installed in late fall, after harvest and any fall fieldwork (disking, sub-soiling, hipping),” Rodrigue says. “A critical measurement is soil moisture leading up to planting. Is the profile full, or half-empty? Is the moisture profile significantly different from the top of the field to the bottom? Installing soil moisture sensors in the winter can give you these answers without having to make assumptions.

“By using sensors in the winter, farmers can be better prepared for their use and understanding during the critical irrigation season. Once you have purchased sensors, why not use them to obtain the maximum benefit?”

While sensors are normally placed in the bottom third of a field during the irrigation season, during the winter they should be placed in the top third of the field to monitor soil moisture profile replenishment from winter and early spring rains, he notes.

“This allows the opportunity for the farmer to learn more about their sensors, without the worry and time constraints of managing a growing crop. Ideally, if available, sensors can also be placed in the bottom third of the field to determine profile differences from top to bottom. In the past, in some years, profile measurements have shown significant differences in soil moisture between the top and bottom of a field at the start of the growing season.”

Sensors should be placed at a minimum of two depths, 12 inches and 24 inches beneath the soil surface, Rodrigue says. “Many Mississippi soils — especially those in the Delta — have a high silt content that causes the soil to seal (crust) and reduce infiltration rates across the soil surface, from both rainfall and irrigation.

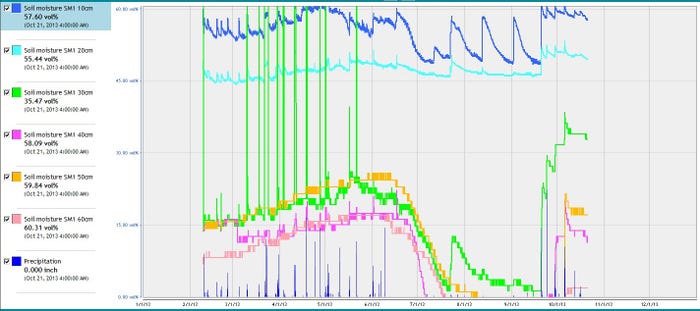

Soil moisture sensor readings (percent volumetric moisture content) at six depths for several months.

“By tracking rainfall and sensor response, farmers can develop an understanding of their soil, its infiltration characteristics (which change continually with each event), the soil profile water- holding characteristics, their field’s moisture regime from top of field to bottom, and finally their soil moisture profile starting point before planting begins.”

Increasing soil organic matter through reduced tillage and cover crops can increase soil water-holding capacity, Rodrigue notes, so winter use of soil moisture sensors can track improvements of water-holding capacity year-to-year.

“By using their sensors in the winter, farmers can be better prepared for their use and understanding during the critical irrigation season,” he says. “Once you have purchased sensors, why not use them to obtain the maximum benefit?”

Farmers can use the NRCS Web Soil Survey (https://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/) to look up the characteristics of their soils, including available water capacity.

“The Mississippi NRCS continues to encourage farmers to install fixed flow meters and enroll in the Delta Voluntary Metering Program,” Rodrigue says. “Contact your local NRCS office about possible financial assistance. NRCS has a continuous signup, so if you don’t have an active application on file, visit your local NRCS office and complete an application, which will be placed in the appropriate ranking pool, per the date of application.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like