“If the glyphosate resistance situation has taught us anything," says Darrin Dodds, "it’s this: Don’t ever think you can’t get resistance to a particular chemistry. We got it with glyphosate — in a bad way — and it has developed with other heavily-used chemistries."

It is a dubious honor, says Darrin Dodds, that Mississippi leads the nation in the number of glyphosate-resistant weeds — and pigweed (Palmer amaranth) is now at the top of that list, he said at the annual joint meeting of the Mississippi Boll Weevil Management Corporation and the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation Cotton Policy Committee.

DARRIN DODDS

Mississippi’s weed resistance problems began developing more than 10 years ago, he says, with glyphosate-resistant horseweed.

“It was a grave concern — a lot of effort was devoted to developing burndown and other programs to address the issue, and we got the problem under control.”

Then resistance developed in other species, says Dodds, who is associate Extension professor of agronomy at Mississippi State University. They included johnsongrass, some ragweed species, and others.

STAY CURRENT ON WHAT'S HAPPENING in Mid-South agriculture: Subscribe to Delta Farm Press Daily.

But Palmer amaranth is the one that is causing nightmares for production agriculture.

“It grows very aggressively, has a very deep root system that allows it to thrive in hot, dry weather, and it produces a tremendous amount of seeds — a single mature plant can set several hundred thousand seeds,” he says. “All this makes it an extremely competitive weed. With glyphosate being used on the majority of our crop acres, the development of resistant pigweed and the rate at which it has spread has created complex issues for agriculture.”

Further complicating the situation is that several weed species have developed resistance to ALS chemistry, which in cotton includes products such as Staple and Envoke.

“We’re seeing more and more cotton acres in Mississippi with Liberty being applied over the top, and there is concern that we may be relying too heavily on this chemistry, particularly north of Highway 6 in the Delta,” Dodds says.

Has taught a lesson

LARRY FALCONER, left, Extension professor at the Delta Research and Extension Center, Stoneville, and Jon Carson, Issaquena County Extension agent, Mayersville, were among those attending the annual meeting of the Mississippi Boll Weevil Management Corporation and the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation Cotton Policy Committee.

“If the glyphosate resistance situation has taught us anything, it’s this: Don’t ever think you can’t get resistance to a particular chemistry. We got it with glyphosate — in a bad way — and it has developed with other heavily-used chemistries.

“My concern is that risk we running Liberty into the ground,” he says. “If we lose Liberty, that will not only be a problem in cotton, but think about all the acres of soybeans we have — if ALS chemistry isn’t working, if glyphosate isn’t working, if Liberty isn’t working, how bad a situation are we going to be in with soybeans and cotton? We’d be left with some PPOs in soybeans (Cobra, Reflex, etc.), but there is already documented resistance to PPOs.

“This scenario may not ever happen, but when somebody tells me they’re spraying three or four times in season with the same product, that raises a red flag for me about possible resistance to that product.”

After “a fairly challenging spring” that brought frequent, and often heavy rains, Mississippi’s 400,000-acre cotton crop (up significantly from last year’s 280,000 acres) was planted in four distinct blocks, Dodds says.

“In addition to weather issues, in a lot of cases we were rushing to get across a lot of acres with the planter and we weren’t able to get back over a lot of fields with a highboy. I can’t tell you how many calls I’ve had this spring from farmers who weren’t able to get a residual down, telling me, ‘My cotton and pigweeds are coming up at the same time.’

“If you aren’t growing cotton with WideStrike in it, or some form of LibertyLink cotton, you’ve had issues. We’ve had tremendous problems with glyphosate-resistant pigweed.”

Treatments for thrips

Thrips have been a problem in cotton for the last several years, Dodds says. “Last year, we sprayed a lot of acres a couple of times for thrips, and there were problems with Gaucho and Cruiser seed treatments breaking out.

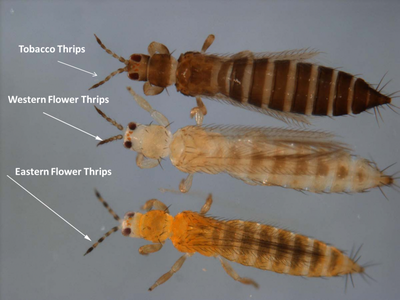

Thrips have been a problem in Mississippi cotton the past several years. — Photo, Mississippi Crops

“This year, most of the cotton insecticide seed treatments that went out were Gaucho-based. We’ve probably averaged one spray on 50 percent of our cotton acres, and in some cases, a couple of sprays. When a grower is paying a lot of money for a seed treatment and then has to spray one or two times for thrips on top of that, it’s cause for concern. I think we will see some changes in seed treatments next year to try and alleviate this situation.”

Angus Catchot, Extension professor of entomology at Mississippi State University is conducting extensive thrips studies, Dodds says, along with work by a graduate student.

“One of the things they’re looking at is whether extensive preemerge spraying for pigweeds is making cotton more susceptible to damage by thrips. We hope to wrap up that study this year.”

Bacterial blight has already been positively identified in several counties this year, he says. At this point I don’t think it’s anything to panic about.

“There have been times it has hurt yield a bit; at other times, it has shown up and then gone away, with little impact. I would encourage you to manage your crop for yield, keep vegetative growth in check with PGRs, keep insects off, and manage as you normally would.

“There’s not a lot you can do about bacterial blight from a pesticide standpoint. It’s certainly not catastrophic in the fields where I’ve seen it.”

Cotton has ability to compensate

With the late start this year, Dodds says, many growers have had problems getting caught up with field work — “it’s like we were constantly behind the 8-ball.

Although much of Mississippi's cotton was planted late, the crop has the ability to compensate, specialists says.

“But if 2013 taught us anything, it’s that no matter how bad things may look, all may not be lost. We were probably later with our cotton crop last year than we’d ever been, but the Good Lord blessed us with exceptional weather in September, and we harvested a record average 1,229 pounds, besting the previous record of 1,024 pounds.

“One of my graduate students harvested a 30-acre trial at Clarksdale that averaged 2,050 pounds, and the grower there had a 240-acre block that averaged over 4 bales — just phenomenal cotton!

“After we finally got the crop planted this year, we’ve been really fortunate with weather. June was one of the wettest I’ve seen, and with about three more well-spaced rains, we should be in pretty good shape with cotton.”

Many growers were concerned this year about thin stands resulting from excess rain, inadequate drainage, and other weather-related problems, Dodds says.

“It’s too late this year, but for future reference: If you have 15,000 healthy plants per acre, I would keep the stand. In our research work, we’ve looked at 15,000, 30,000, 45,000, and 60,000 plants per acre, and the yield results were flat-line — there was no statistical difference between 15,000 plants and 60,000 plants.

“I would never start out planting just 15,000 seeds per acre,” Dodds says, “because you might not get as much germination as you’d like, or you might have other stand problems. I’m comfortable planting 40,000 to 45,000 plants per acre to provide a margin of error if there are stand losses for any reason.

“But next year, if you’re faced with deciding whether or not to replant, and you’ve got 15,000 healthy plants per acre, and you’re averaging a plant every 1 foot, I advise keeping the stand. It may look pretty thin early on, but cotton can get big, branch out, and fill those gaps.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like