Dry winter an omen of long-term drought?

The La Niña meteorological phenomenon that will influence this winter’s weather and bring warmer, drier than average weather to the Southwest, Southern Plains, Gulf Coast states, and the Southeast 'will likely exacerbate drought conditions in these areas,” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists said in their October 21 forecast, noting that it also has the potential “to bring weather extremes” to parts of the nation.”

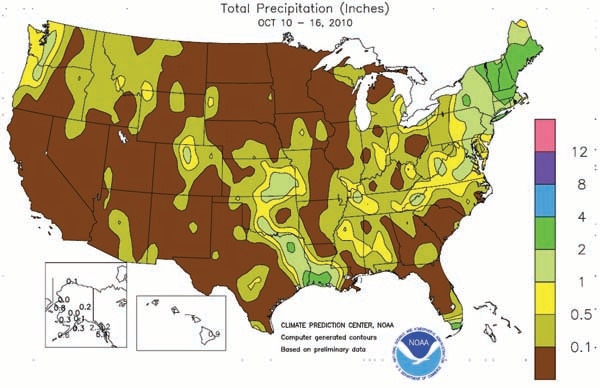

At October’s end a year ago, fields all over the Mid-South were saturated from weeks of torrential rains, which continued well into the winter.

At October’s end this year, much of the region was showing a rainfall deficit for the 10-month period. Fall pastures hadn’t had enough moisture to germinate seed, wheat was slowing coming up, and heavy soils were cracked like midsummer.

A strong El Niño, which heated up the equatorial Pacific Ocean, was blamed for triggering 2010’s monsoons; now, weather gurus say a La Niña, the opposite phenomenon that results from cooler Pacific temps, will influence this winter’s weather and bring warmer, drier than average weather to the Southwest, Southern Plains, Gulf Coast states, and the Southeast.

“This will likely exacerbate drought conditions in these areas,” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists said in their October 21 forecast, noting that it has the potential “to bring weather extremes” to parts of the nation.”

“La Niña will strengthen and persist through the winter months,” says Mike Halpert, deputy director of the agency’s Climate Prediction Center, a division of the National Weather Service (NWS).

At mid-October, the NWS was reporting 92 percent of the state of Mississippi experiencing abnormally dry, moderate drought, or severe drought conditions. Rainfall deficits ranged from 19.08 inches below normal at Greenville, Miss., to 9.3 inches below normal at Mississippi State University.

September was the third driest on record for Mississippi and January-September the 11th driest. September was the second driest on record for Louisiana, and January-September the 11th driest.

In its most recent seasonal assessment of drought, NOAA is predicting that drought will persist or intensify over much of the Mid-South, lower Southeast, and southwest Texas.

Drought expected to expand

While the forecast points to improved rainfall conditions from November through January in the Northwest, Upper Midwest, and Ohio Valley, it says drought is expected to “develop and expand into much of the Southeast not currently in moderate drought, along with portions of the Southwest … A large area of drought development is forecast for most of the Southeast … including parts of western Arkansas, eastern Texas, the southern Applachians, and along the Gulf Coast.”

Several areas are classified as in “severe,” “extreme,” or “exceptional” drought, and others “abnormally dry” or “moderate drought.” Stream flow and soil moistsure readings were “quite low” over much of the region.

Adding to the drought picture is the lack of tropical moisture during this year’s hurricane season.

NOAA’s global climate analysis showed January-September as the second warmest on record for world land surface temperatures, behind 2007. The global average ocean surface temperature for the nine-month period was also the second warmest on record, behind 1998.

The global combined land and ocean surface temperature for the period tied with 1998 as the warmest on record.

Much of the Deep South “should prepare for a warmer and drier than average winter, which means drought conditions will likely continue to worsen, with an abnormally high threat for wildfires,” the NOAA Winter Outlook notes.

“Typically, during a La Niña weather pattern, the main storm track cuts across the Pacific Northwest, and the northern branch of the jet stream is dominant. This weather pattern favors flooding in the Northwest and a deep snow pack in the northern Rockies.

“But the southern tier of states experience a less active storm track, and it’s this general lack of storms that leads to below average precipitation in those states. With the primary storm track remaining off to the north, cold air masses are typically not able to dive as often into the Deep South, leading to the overall warmer winter.”

The NOAA scientists note, however, “when storm systems do affect the South during a La Niña weather pattern, explosive severe weather episodes can often occur throughout the winter season, with overall weather conditions remaining relatively warm.”

Severe, prolonged drought ahead?

While this winter’s outlook is based upon La Niña’s influence, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in a paper reviewing recent literature on drought, contends that the U.S. and many other heavily populated countries face a growing threat of severe, prolonged drought in coming decades.

The analysis of 22 computer climate models and previously published studies by NCAR scientist Aiguo Dai projects that warming temperatures will bring increasingly dry conditions over much of the earth over the next three decades — perhaps on a scale not seen in modern times.

In just 20 years, vast areas of the world are going to be far drier than they are today, the study says.

“A striking feature is that aridity has increased since the late 20th century and will become severe drought by the 2060s over much of the Americas, southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Australia, and southern Europe.”

Areas where drought is expected to decrease include much of northern Europe, Russia, Canada, Alaska, and some areas in the southern hemisphere.

But, Dai says, “the increased wetness over the northern, sparsely populated high latitudes can’t match the drying over the more densely populated temperate and tropical areas.

“If the projections in this study come even close to being realized, the consequences for society worldwide will be enormous.”

A previous study by Dai and his colleagues found that the percentage of Earth’s land areas affected by serious drought more than doubled in the period from the 1970s to the early 2000s, and that some of the world’s major rivers are losing water.

By the 2030s, Dai’s study indicates, some regions in the U.S. and overseas could be experiencing “particularly severe�” drought conditions.

While he cautions that his findings are based on the best current projections, “what actually happens in coming decades will depend on many factors, including actual future emissions of greenhouse gases and natural climate cycles such as El Niño.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like