Building a cow value bell curve shows us what real cow depreciation looks like, and it's not the straight-line depreciation economists and the IRS use.

Beef Producer first broached this topic at some length in June 2017 online and in the paper magazine in August 2017 with the story Consider the no-depreciation cow-calf operation. The overwhelming evidence is that heifers actually appreciate from weaning until typically 3 years old, then hold steady value until they are about five years old, then begin to depreciate rapidly.

Wally Olson, a livestock producer from Claremore, Oklahoma, teaches this concept in his marketing schools. He says beef producers have the option to sell cows before they begin to depreciate and potentially make huge progress in growing net worth. Olson has done this himself for many years.

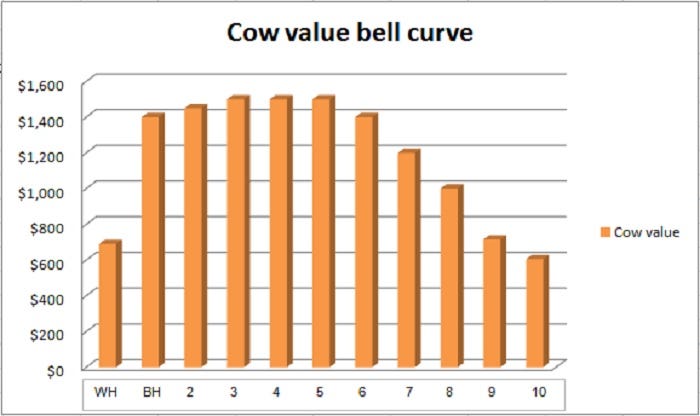

A look at the chart labeled "Cow value bell curve" shows this clearly. It is based on heifer and cow prices in the Southern Plains last winter. Note that weaned heifers have roughly the same value at the older cows, a relationship Olson says is typical throughout the cycle of cattle prices. The biggest depreciation on this chart and in real life commonly comes in years 7 through 9 of a cow's life.

Notice the weaned heifers on the left side and old cows have roughly the same value.

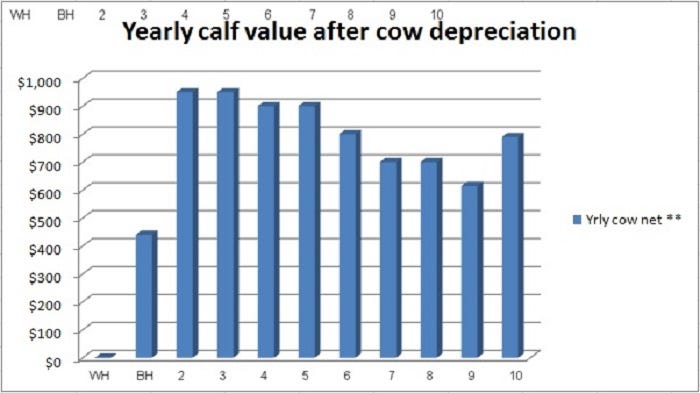

This should change much about the way we think of cow depreciation and its effects on calf returns. For a visual representation of that relationship, check out the graph "Yearly calf value after cow depreciation." Note that in the first four productive years of a cow's life there is no actual cow depreciation to count against the calf, at least from a standpoint of managerial accounting. This says if you could sell cows in the last year or two of their peak value, you would never pay that depreciation and could arguably keep all that calf price to weigh against your cost structure.

Another interesting anomaly of cow depreciation is that very oldest cow. If you could buy these well-depreciated cows and keep them healthy with the right kind of groceries, they could offer you most of the price of a calf as a return on your investment and take little away in depreciation when you sell them.

Olson has been heard to say, "I don't mind owning old cows. I just don't want to make them."

Here's a review of an explanation how such a no-depreciation cow operation might work from our previous story:

"The classic model of a cow-calf operation is that of an asset-management business: It holds great gobs of capital in the form of depreciable assets, spends varying amounts on upkeep and some inputs, and tries to overcome depreciation and create profitability by selling a product (calves). It's that depreciating, non-working capital that creates such a headwind.

"Here's an alternative to the traditional cow-man's ranch: Cows are raised at home or can be bought as light heifers and then kept no longer than peak value (appreciation) at 4-5 years old. Then they are sold and younger stock takes their place. This sells a major asset (cows) before depreciation begins to rob profit from the operation. Selling cows younger also increases monetary turnover and therefore can further increase profits.

Most often, heifers are raised or bought at about 450-550 pounds. Commonly they increase in value by $1,000 or more and raise two or three calves before moving on," Olson says.

In most cases on home-raised heifers you would sell those which don't breed the first time either as feeder heifers, or you would give them another opportunity to breed and sell them as a later-bred heifer. Either method could offer you profits if your cost structure is low enough.

For additional information about this topic, see Alan Newport's blog, The cow bell curve went flat.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like