And then there was one: John McReynolds, dairyman

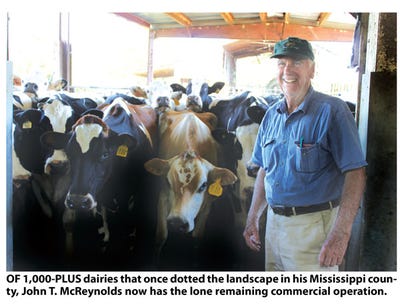

Of the 1,000-plus dairy enterprises that once dotted the landscape of Oktibbeha County, Miss., just one commercial operation is left — McReynolds Dairy. John T. McReynolds, who milked his first cow at age 6 on his father’s farm, is the lone survivor of the county’s once-teeming industry.

Oktibbeha County, Miss., was once known as The Dairy Center of the South, boasting more than 1,000 dairies, several milk processing plants and creameries, and herds of the finest dairy animals anywhere.

Now, abandoned silos dot the landscape, and much of the rolling land has been put in trees, or is home to beef cow herds, or has been developed.

Of those many hundreds of dairy enterprises, just one commercial operation is left — McReynolds Dairy.

John T. McReynolds, who milked his first cow at age 6 on his father’s farm, is the lone survivor of the county’s once-teeming industry (Mississippi State University has a dairy just up the road from him, but all its milk is used by the university’s Dairy Sciences Department).

John T. McReynolds, who milked his first cow at age 6 on his father’s farm, is the lone survivor of the county’s once-teeming industry (Mississippi State University has a dairy just up the road from him, but all its milk is used by the university’s Dairy Sciences Department).

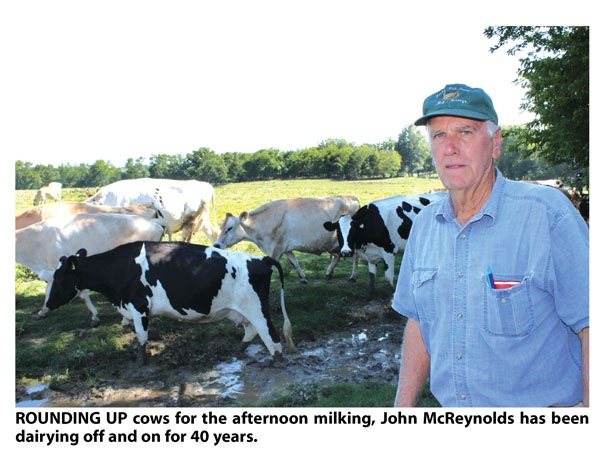

“I’m 75 years old, and I know I can’t keep at this forever,” he says. “I’ve been dairying, off and on, for 40 years, and every year it becomes more of a challenge. Because there are only a handful of dairies left in this part of the state, it’s very difficult to get equipment serviced, large animal veterinarians are becoming scarcer and scarcer, and there isn’t a support infrastructure for the business any more.

“It just isn’t a career that young folks want to get; it’s demanding, confining work —hot in the summer, cold in the winter, muddy when it rains, dry as dust when it doesn’t.”

But, he says with a glint in his eyes, “That first cow I ever milked as a boy — I loved it! Our family had been dairying here for several generations. My father, who worked for the Federal Land Bank for 38 years, had a Jersey herd in the late 1930s on land that is now Plantation Homes subdivision. There were five of us kids and we milked by hand and put the milk out on the road twice daily for the truck to pick up.

“In the mid-1940s, Daddy got out of dairying, but by then I had dairy projects in the 4-H Club, raising cows, milking them, and showing them. When I got into high school, though, the cows competed with football and other activities, and I talked Daddy into letting me sell them so I’d have more time for my (he laughs) studies.”

He later went to Mississippi State, earned a degree in general agriculture, then farmed for a while with his father, who by then had a 600-head herd of registered Angus. He went back to the university and earned a master’s in agricultural economics.

“At the end of World War II,” McReynolds says, “there were 27,000 Jersey cows in this county and every hill had a dairy barn on it. A lot of the milk produced here had gone to the war effort. Borden had a huge milk processing plant here and there were other plants and several creameries.”

First herd of Jersey cows

Dairying in the county traces to the mid-1800s, when Col. W.B. Montgomery, a local dairyman, went to the Isle of Jersey and brought back a herd of Jersey cows, pioneering what became a thriving Jersey industry. He eventually had the largest herd in the South and a national champion Jersey bull.

The growth of dairies here led to increased emphasis on grasses, clovers, and other forages, and a thriving business developed in buying and selling dairy and beef cows, which were shipped all over the country from the Starkville railroad station. Today, there are Jerseys all across the U.S. that trace their lineage back to that 1800s herd.

It was due in large part to Montgomery’s influence that the state legislature, in 1878, passed an act establishing Mississippi Agricultural & Mechanical College (now Mississippi State University) at Starkville.

It was due in large part to Montgomery’s influence that the state legislature, in 1878, passed an act establishing Mississippi Agricultural & Mechanical College (now Mississippi State University) at Starkville.

“Dairying here probably peaked in the 1960s, and it has been downhill since then,” McReynolds says. “I think a major reason for the decline has been availability of labor. It’s a demanding, confining routine — twice a day, every day of the year — and not many people want to do it.

“Dairy economists say you need a 300-cow herd to have an economically viable operation nowadays. With equipment and facilities, you’re talking easily $1 million just to get started. If you’ve got that kind of money, there are other less demanding investment options.”

After earning his graduate degree, McReynolds worked as a loan officer for the Farmers Home Administration, and “when this farm came up for sale, I looked it over and thought to myself, ‘Dang, this is really a nice place.’ It had a world of good bottomland that would grow anything.

“Shortly after I bought the place, John Beckum, who lived on the property, came over to meet me. We talked and he allowed, ‘I guess you and I can get along,’ so I put a beef cattle herd on the land and I continued working for FHA.

“Later, John complained that he couldn’t make a living working with just beef cows, so I went to the sale barn and bought a few plug dairy cows to give him something more to do. That’s how I kind of backed into dairying again. I started buying better cows and adding facilities, and just got bigger and bigger.”

After a stint with the Federal Land Bank, and then as agency manager for Farm Bureau, in 1972, “I decided to become a fulltime dairyman. And I’ve been doing it ever since, except for the period I dropped out in the 1980s under the government’s Dairy Termination Program. I found out pretty soon, though, that I couldn’t make a living growing 1,200 acres of soybeans, and after five years I got back into dairying.

“In 1996, I entered into a partnership with Alva Rivers — one of the best things I ever did. He told me he’d do everything related to the cows, but he didn’t want to fool with paying bills, keeping books, or have anything to do with the business end. He brought with him 60 Jersey heifers and 40 bred Holsteins.

“He was as good a cowman as I’ve ever known. We’d both already satisfied our egos by cleaning up on prizes at the state fair. We worked well together — never had a cross word about anything.” (Rivers died in 2001.)

Four pasture systems

Over the years, McReynolds says, “I’ve milked as many as 160 cows, or as few as 70-80. Now, we’re milking 115-120.

“I have one herd of registered Holsteins, another of registered Jerseys — about 60 milking cows of each. There are another 100 bred and open heifer calves. We keep calves in pens until they’re 2-1/2 months old, wean them, and then they go into the barn on hay and grain until they’re ready to go onto pasture.

‘We have four pasture systems: one for milk cows, one for dry cows, one for open heifers, and one for bred heifers. There are eight pastures used for grazing ryegrass.

“All our breeding is by artificial insemination. There has never been a bull on the place since I started in 1966. AI gives me access to the world’s best bulls. I purchase semen from Select Sires and ABS Global.”

“All our breeding is by artificial insemination. There has never been a bull on the place since I started in 1966. AI gives me access to the world’s best bulls. I purchase semen from Select Sires and ABS Global.”

He says the average is about 14,000 pounds of milk for the Jersey herd and about 16,000 for the Holsteins. “We probably should be doing better, but with the atrocious weather of recent years, the cows just don’t perform to their maximum potential.”

The milking parlor is a double 4 herringbone layout, with four milkers on each side, and Germania automatic takeoffs.

“We can milk eight cows at a time, about 40 per hour,” McReynolds says. Milking usually takes 2-1/2 hours morning and night, starting about 4 a.m. and 5 p.m.

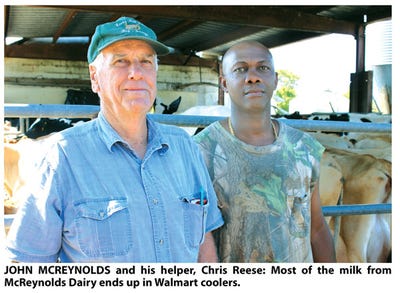

His helper, Chris Reese, handles the milking operation.

“It was a good day when Chris came to work for me,” McReynolds says. “He is now in his 20th year with me, and in all that time he has never missed a single day of work. He likes the work, he knows the cows, and I could not ask for a better employee than Chris.

“He comes morning and afternoon, sanitizes the equipment with a chlorine wash, rounds up the cows and heads them into the holding pen. In hot weather, we can spray them with misters to cool them down while they’re waiting. They go through the cleaning station, where their udders are washed down, and then into the milking parlor. All the manure is washed into grates and then flows downhill to the treatment lagoon.”

The milk is stored in a 1,250-gallon tank that maintains it at 38 degrees until it’s picked up. “Our milk goes to Dairy Fresh at Hattiesburg, Miss.,” McReynolds says, “but from there most of it goes to Walmart and is sold under their own label. A tanker truck comes through every other day to pick up milk from us and the handful of other dairies that are still scattered across northeast Mississippi.”

In 2009, he says, the price of milk bottomed out at about 1975 prices, “but the price for feed and everything else has gone steadily upward. Our biggest cost items are ‘The Three Fs’ — feed, at $300 or more per ton; fertilizer, at $400 or more per ton; and fuel, at $3.50 to $4 per gallon.

“China has run the prices of corn, cotton, and soybeans sky high. I’m proud that farmers can get $7 or $8 for corn and $12 or $13 for soybeans, but it kills us on feed prices. We’re surviving right now because milk prices are inching back close to what they were in 2008.

“My best year was 2008; we had good milk production and good prices. Ironically, my worst year was the following year, 2009; there was a lot of overproduction and China pretty much dropped out of the cheese market. Our milk prices tend to follow what the cheese market does, and we saw a 60 percent price drop that year.”

Weather problems in 2009

2009 was also the worst weather year he ever experienced, McReynolds says.

“Starting in April, it rained steadily for six weeks, and I lost my ryegrass hay crop; a lot that I had cut I never got to roll up. Then, May/June brought a six-week drought that got our second cutting of hay and our pastures, and just killed us.

"The drought was followed by an extended rainy season that lasted through December — we got 38 inches of rain, half our yearly rainfall, in six weeks. My johnsongrass hay was looking good (unlike row crop farmers, we dairymen love johnsongrass), but it was so wet I had to have fertilizer applied by air.

"The drought was followed by an extended rainy season that lasted through December — we got 38 inches of rain, half our yearly rainfall, in six weeks. My johnsongrass hay was looking good (unlike row crop farmers, we dairymen love johnsongrass), but it was so wet I had to have fertilizer applied by air.

“Then, armyworms hit, and I had to spray for them. But I never got to cut that grass, because of all the fall rains; I had to plant my winter ryegrass by air. I had about 90 percent loss of my hay crop that year.

‘I try to put up all the hay I can; I like to get at least 1,200 rolls, but wasn’t able to do that the last two years due to adverse weather. I had to buy $12,000 worth of hay each year to get through the winter.”

Temporary grazing is ryegrass pasture — “we live and die by ryegrass,” McReynolds says. “It’s a wonderful high protein forage, both for grazing and baling. We’ll plant about Sept. 1 and hope to be able to start grazing by Oct. 12-15. We can usually continue grazing until about May 14.

“We also can bale it at high moisture, 50 percent to 60 percent, and wrap it in white plastic, which keeps it from deteriorating, and store it right in the field. The plastic wrap is cheap storage; we don’t have to have a lot of barn space for the hay.”

He has a 24-ton feed storage tanks, and uses about a ton per day. This tank contains 20 percent high energy protein feed and another 10-ton tank contains a pelleted 14-16 percent protein heifer ration.

As he strides briskly out into the pasture to whistle up cows for milking, McReynolds keeps a pace that a younger man might envy. He knows each cow, how many calves it’s had, it’s milk-producing ability, its particular temperament.

So, what happens if, and when, he decides to close the doors on his dairy?

“I probably would raise heifers to sell to dairies elsewhere,” he says. “I don’t think I could ever completely get away from cows.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like