March 26, 2019

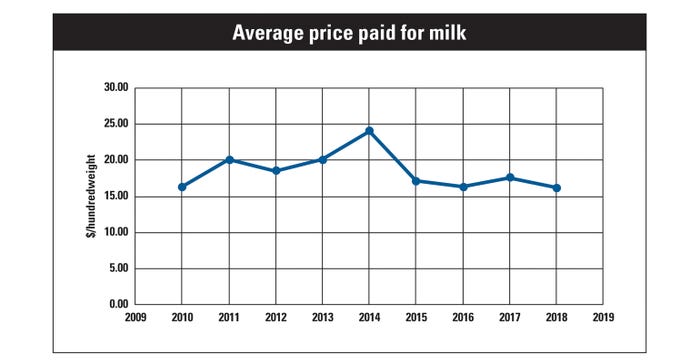

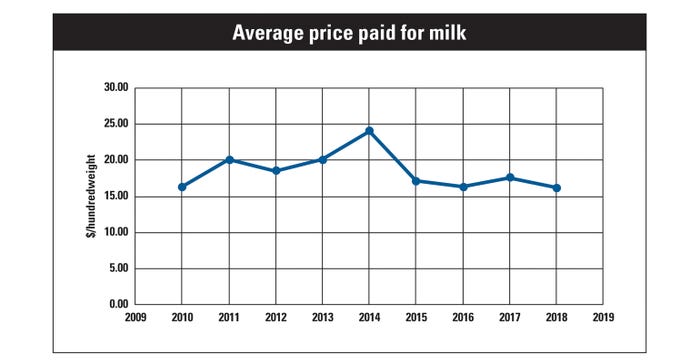

After four years of depressed milk prices, the first months of 2019 brought some cents. All-milk product prices in March were forecast by the USDA Economic Research Service to reach $17.00-$17.60 per hundredweight. One factor the U.S. Dairy Export Council attributes to this is the milk supply’s limited growth. In the United States, milk production is forecast at 0.4 billion pounds lower than a year ago.

The slight price rise is also because of improved demand from China, Southeast Asia and Mexico. Additionally, the European Commission removed 247,857 tons of skim milk powder through public intervention, a third of which it sold in January. The U.S. Dairy Export Council says the commission only held 3,651 tons in early February. Even with this movement, U.S. exports for 2019 are forecast by the ERS to be 1.0 billion pounds lower on a skim-solids milk-equivalent basis, and 0.2 billion pounds lower on a milk-fat milk-equivalent basis.

The average price paid for milk per hundredweight last peaked in 2014, when exports were on the rise

Belts tightened

Past market downturns primarily affected conventional milk producers, while organic and grass-fed dairy demand continued to grow. But, beginning in 2017, those alternative markets felt the pinch, too. To survive financially, dairy farmers diversified their operations to include off-farm income and scrutinized financial inputs for ways to reduce costs. Several operations added cows and worked to boost production per cow. With low milk prices expected to continue for a few years, it’s now time to evaluate one’s financial capacity to keep the farm.

“It’s critical to understand your financial costs and position,” explains Shannon Neibergs, Extension economist and director of the Western Center for Risk Management Education at Washington State University, Pullman, Wash. “Ask yourself: Do you have borrowing capacity to maintain cash flow until you can recover profitability?”

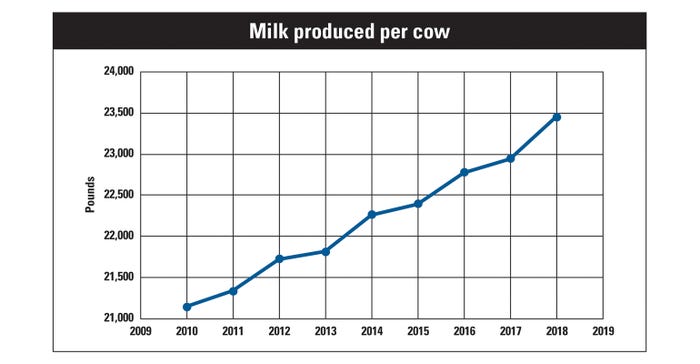

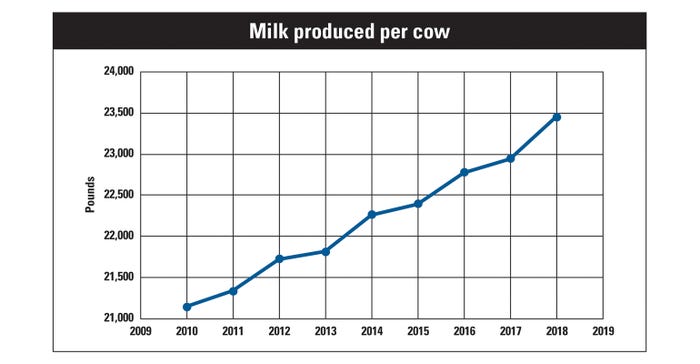

Neibergs also encourages producers to scrutinize how to produce milk more efficiently. Statistics from the USDA show that farmers in the National Agricultural Statistics Service’s 23 major dairy states are on this track. Production per cow increased 21 pounds from February 2018 to February 2019. The 1,838 pounds of milk per cow per month is the most recorded since the 23-state series’ inception in 2003.

“I think it’s also time to renew emphasis on replacement efficiency,” Neibergs says. “Do you produce or buy replacements? Are there any efficiencies to gain? Can you promote longevity in the livestock you currently have?”

Or is your herd too big? It may be time to reduce herd size to reduce replacement and feed costs. “Selling some of your herd can generate cash to pay down current debt obligations, and look to a more efficient future,” Neibergs adds.

USDA numbers show that many farmers have already reduced their herds; dairy cow slaughter rates are topping 2018 levels, and there were 77,000 less milk cows on farms in February 2019 than the year prior.

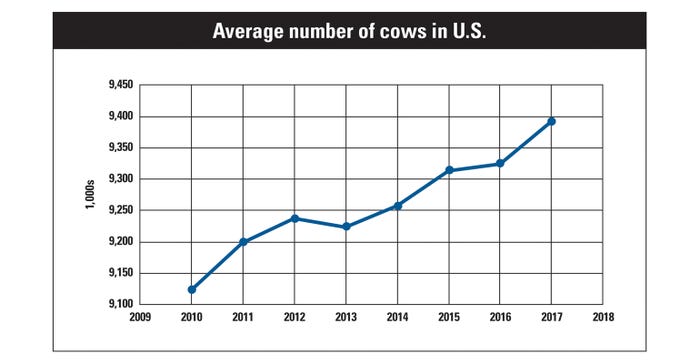

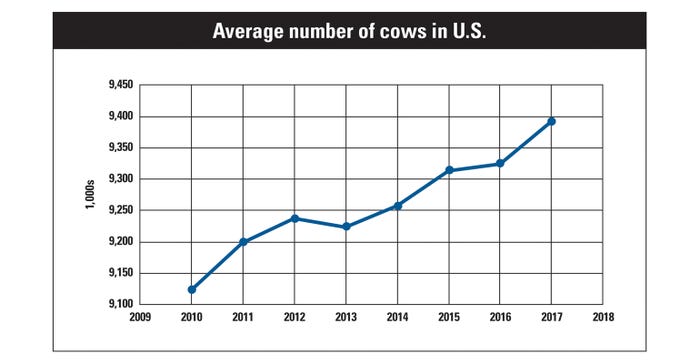

Since 2010, dairy farmers have worked to ramp up the amount of milk produced per cow, due in part to the need to maintain cash flow.

It’s in the trade

The dairy outlook is critically dependent on world trade. The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement awaits final approval by Congress, and the U.S.-China trade deal is under negotiation. Neither is expected to be in place before autumn this year. Milk prices likely won’t bounce back afterward, either.

“The trade deals will only put us [in the U.S.] on a level playing field and improve our competitiveness,” Neibergs says. “Milk prices are low internationally. Geopolitical events, such as Russia’s food embargo on the European Union, affect everyone. Prices fluctuate according to milk supplies from Europe, New Zealand, Australia and the U.S. It’s very frustrating that political and trade decisions beyond farmers’ control dictate milk prices.”

The conundrum in the dairy business is that when prices fall, cow numbers can rise as producers look to maintain cash flow. Note: For all states, only data through 2017 are available.

Dairy alternatives

Another factor that affects milk prices is that U.S. consumers now drink less fluid milk, which historically was the highest-valued component sale of milk. USDA calculates that people drank 98 pounds less per person in 2017 than in 1975. A third of that, 33 pounds per person, dropped from 2007 to 2017.

According to recent figures from Nielsen and the Plant Based Foods Association, nondairy milk sales jumped 9% from June 2017 to June 2018. Plant-based milk now represents 15% of the total market. During that same period, sales of fluid milk fell 6%.

While this does cause alarm, a 2018 Cargill survey found half of U.S. dairy consumers prefer to purchase both dairy and plant-based alternatives. Other recent studies, reports and surveys now claim consumer diet and taste preference for dairy-based products over plant-based, and that fully avoiding dairy can cause iodine deficiency.

Farm bill help

U.S. farmers, particularly those milking between 200 and 500 cows, will benefit from two revamped support programs in the 2018 Farm Bill: Dairy Market Coverage and Dairy Revenue Protection. DMC could add $1 per hundredweight to producer milk prices. This may help farmers stay in dairy and support a sustainable supply of U.S. milk.

Hemken writes from Lander, Wyo.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like