I suspect most cow-calf operators have seen the data relating early-calving heifers and cows to bigger calves, earlier-maturing offspring and longevity when defined as ability to stay in the herd.

A new study from western Canada again reiterates these relationships.

This is valuable information, yet I believe most folks are missing some logical inferences from this data. Primarily the lesson is these are the most reproductive cows in their environment and management system. These are the future of the herd to replace themselves and produce suitable bulls.

Now that I've given you the punch line to chew on, I'll quickly review the Canadian study and then we'll continue: The trial used 211 black Angus and Angus-crossbred heifers from the Western Beef Development Centre in Saskatchewan. This was a spring-calving herd and the data came from the period 2001 to 2017. The breeding season began June 20 each year and lasted about 65 days.

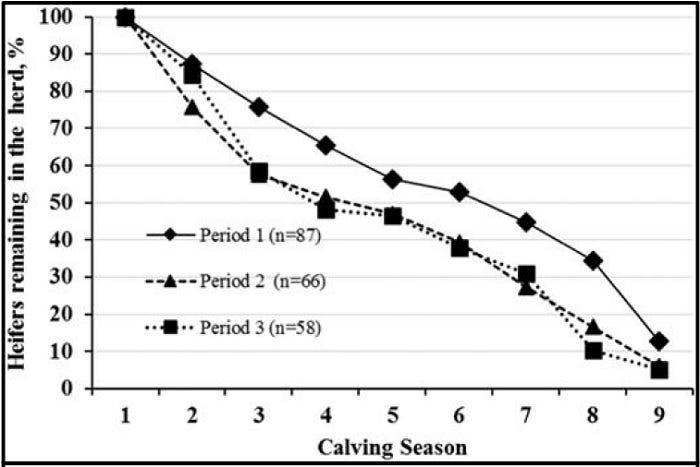

The researchers said heifers that calved with their first calf during the first 21-day period of the calving season remained in the herd longer than those that calved in the second 21-day period or later.

They also shows females that calved early as heifers tended to calve earlier throughout the remainder of their productive lives than the females that calved later in their first calving.

This matches results of a study on more than 16,000 females done at the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center in Nebraska.

In the Canadian study, heifers that had their first calf during the first 21-day period of the calving season lasted an average 7.2 years, versus 6.5 years for second-period heifers and 6.2 years for third-period calvers.

Average longevity in the USMARC heifers that calved in the first, second or third period was 8.2, 7.6 and 7.2 years, respectively.

So, to get back to my point: There is a clear genetic and hormonal difference, and I suspect a phenotypic one, between these early breeders and the later ones. Whether they are being fed a lot or a little, they are obviously more suited to their environment and management conditions. The difference is inherent.

We need to face that fact we have made cattle extremely unsuited for range conditions by breeding seedstock for feedlot production as essentially a single-trait selection criteria. This was a flawed idea whose time to die has come, along with the "lean and efficient" concept. Cows and bulls that can put on some fat and carry it into the winter will produce calves that can get fat easily and finish early, especially in a feedlot environment.

Moreover, this reiterates the claim by African rancher-consultant Johann Zietsman that reproduction is a survival trait and therefore is highly heritable.

For a reference from nature, several years back I spent quite a few winter days culling whitetail deer does and butchering them with a friend in the Texas panhandle; I remember two important facts from this exercise. Regardless of the conditions, drought or no drought, even if the does seemed a little thin in appearance, I can't recall ever butchering one that wasn't reasonably fat or one that was not pregnant. And we aged them from yearlings to more than 9 years old. They were simply suited to survive and reproduce in their habitat.

I believe this is what we need to recapture in our cattle. The right kind of animals, the ones that show high capacity for reproductivity, are the only kind of cattle we need.

The opinions of this writer are not necessarily those of Farm Progress/Informa.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like