Where food insecurity exists today could be famine tomorrow as the Russia-Ukraine conflict brews the perfect storm in the Black Sea that could set the world on a further trajectory of increased food insecurity.

“In Ukraine, it is one of the worst crises which I have seen, and I have seen many,” shares Arif Husain, chief economist of the United Nation’s World Food Programme during testimony in front of the House Agriculture livestock and foreign agriculture subcommittee hearing on April 6.

Husain notes that what is happening in Ukraine has huge ramifications for the rest of the world. Steep rises in international prices for basic staples – notably wheat and corn – in recent weeks reflect a food price environment that resembles the 2008 or 2011 crises.

Given the impacts Russia’s invasion into Ukraine is having on the world food supply, much of the hearing focused on what can be done by the U.S. government to address expected food insecurity and shortages in Ukraine and around the world.

Members heard from two panels of witnesses, the first being administration officials, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service Administrator Daniel Whitley and U.S. Agency for International Development Assistant to the Administrator for the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance Sarah Charles, and the second being a panel of cooperators from the U.S. Dairy Export Council, the National Association of Wheat Growers, the United Nations World Food Programme and Catholic Relief Services.

“Medium- and long-term global food security implications of the Ukraine crisis will depend on the duration of the conflict,” Husain notes. “If the conflict is resolved on the ground within the next five to six weeks, there could be a quick return to pre-conflict realities. However, if the conflict continues beyond two months, we face a completely different situation.”

According to the Global Hunger Index 47 countries have high levels of hunger in 2021. The war in Ukraine is estimated to bring this number to more than 60 countries in 2022.

On the other side of Capitol Hill on April 6, Sens. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, and Sen. Roger Marshall, R-Kan., hosted members of Ukrainian Civil Society - Hanna Hopko, Daria Kaleniuk and Maria Berlinska - for a discussion about Russia’s war in Ukraine and what it means for global food security and agriculture.

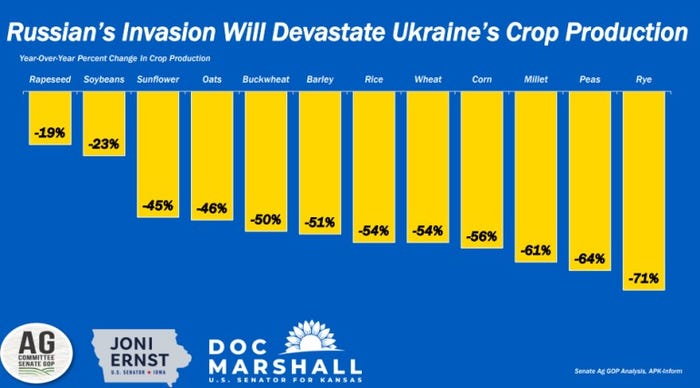

In her opening remarks, Ernst noted that approximately 400 million people are dependent on Ukraine and Russia for food, and that production this year will drop 40-45% in Ukraine due to the lack of available fertilizer, pesticides and diesel fuel – which is being used by the military to fight the war. Ernst says that Russia was “using food as what we call a ‘quiet weapon,’ and they are targeting agriculture.”

Ernst explains that at least 14 African countries import at least half of their wheat from Russia and Ukraine. Black Sea exports are now shut down as no carriers want to take the risk in an active war where ships could be damaged by missiles.

Kaleniuk of the Ukrainian Civil Society made a passionate plea to help protect Ukrainians still in the country, especially those farmers who are trying to plant this year’s crop. She shares the world will face starvation, hunger riots and refugee migration without the Ukrainian food supply. “There is no sufficient alternative to cover the gap,” she says.

She estimates that no more than 70% of spring crops will be planted in 2022, with the biggest loss of acres in the northeast, east and south regions of the country. She also says farmers plan to plant less corn, turning instead to more soybean and sunflower planting. The planting campaign is also under risk of failure due to lack of finance and availability of diesel fuel, she shares.

Role of U.S. commodity food aid

USAID Assistant Administrator Charles told the House Agriculture Committee members that she is on the phone daily with European counterparts to assist in the response to Ukraine in helping support their exporting efforts as well as coordinating humanitarian response as the food price impacts continue to spiral.

Charles says the last farm bill allowed for a shift away from some greater flexibility between direct commodity aid and cash assistance. She sees a “critical role for U.S. sourced food commodities where local markets can’t support acute food needs of those most in need.”

However, supply chain disruptions have limited the purchasing power of U.S. commodities as costs have increased to move food around the world.

USAID uses resources authorized under Title II of the Food for Peace Act and appropriated under the annual agriculture appropriations for both emergency and non-emergency food assistance programs. In Fiscal Year 2021, USAID provided nearly $2.3 billion in Title II Food for Peace Act assistance, funding the procurement of nearly 1.7 million metric tons of food from the United States to serve a total of almost 28 million beneficiaries in 35 countries. Nearly 86% of Title II assistance was for emergency responses and approximately 14% was for non-emergency programming.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like