January 19, 2024

It won’t be long before no one in Wisconsin has a fond memory of attending a one-room country school.

Nearly all of Wisconsin’s one-room schools closed by the mid-1960s, so if you do the math, that means most people who remember attending a one-room school are now in their 70s, 80s or 90s. In another 15 or 20 years, well, there won’t be many of them around to tell their stories.

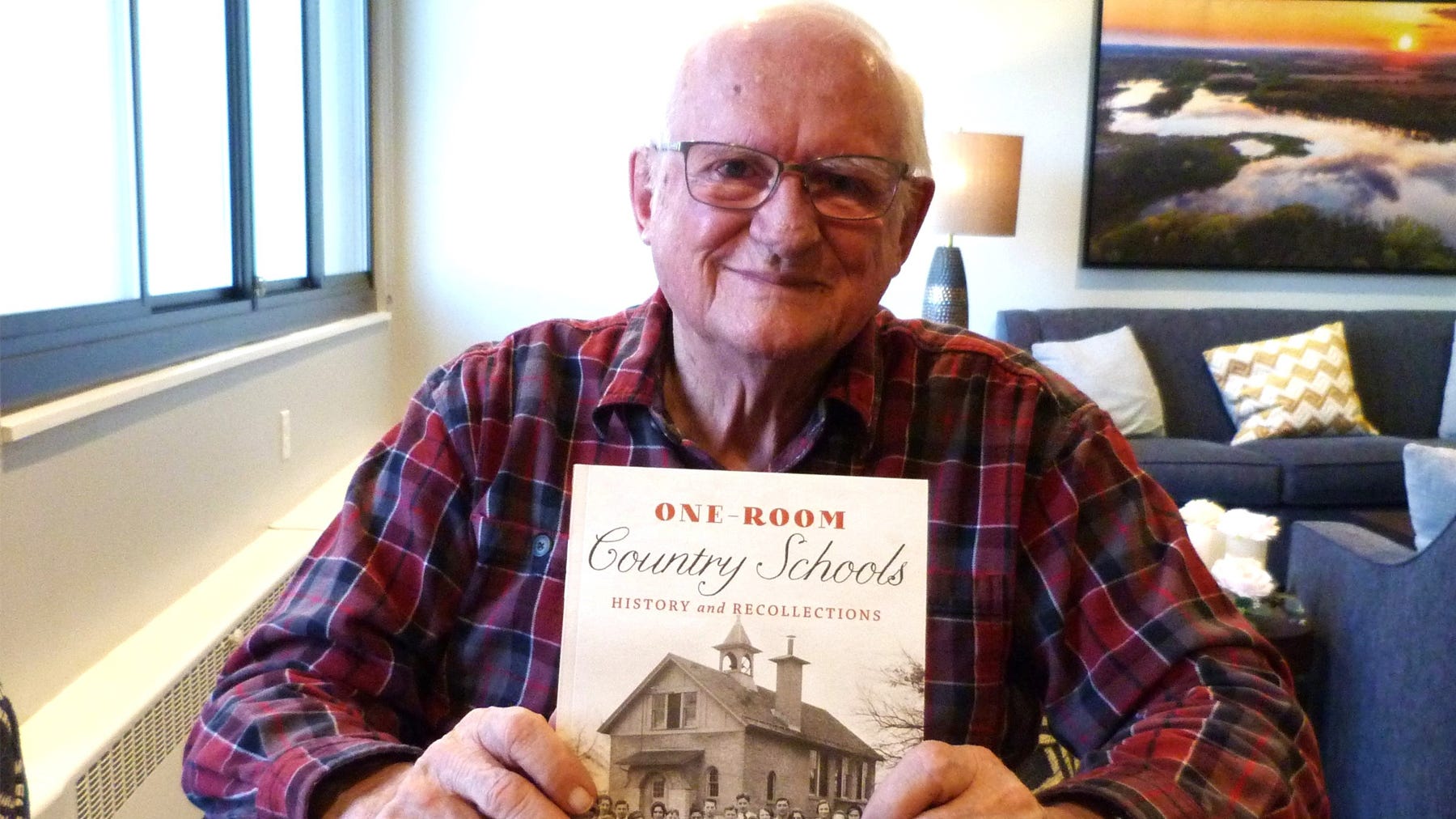

One person who has a clear recollection of one-room-school days is noted Wisconsin historian Jerry Apps, who wrote a book about the topic called “One-Room Country Schools: History and Recollections.” Apps, 89, grew up on a farm in rural Wild Rose in Waushara County and attended the Chain-O-Lake School in the town of Wild Rose, Wis.

In this two-part series, Apps recalls the history and some of his favorite stories related to Wisconsin one-room country schools.

Apps is a former county Extension agent and professor emeritus for the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of 45 nonfiction books and 10 novels, including historical books on topics such as barns, cranberries, cheese factories, breweries and farming with horses. He is also a frequent guest on Wisconsin Public Television, where excerpts of his books come to life as he tells his stories. One of his books, “Meet Me on the Midway: A History of Wisconsin Fairs,” will be featured on WPT in 2024.

ALL ABOUT ONE-ROOM SCHOOLS: Well-known Wisconsin historian Jerry Apps has crystal-clear memories of his eight years in a country school near Wild Rose, Wis. He wrote a book about one-room schools called “One-Room Country Schools: History and Recollections.” (Jim Massey)

One-room school heyday

According to Apps, during the 1937-38 school year, Wisconsin had the largest number of public one-room country schools in the U.S., with 6,181. There were 7,700 school districts in Wisconsin at that time. Today, there are 421 school districts in the state, according to the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

The Private School Review indicates Wisconsin currently has 49 Amish one-room private schools attended by 1,027 students. The LaPoint School on Madeline Island, a 20-minute ferry ride from Bayfield in far northern Wisconsin, is perhaps the only public one-room school still in existence in the state, with 15 students from kindergarten through fifth grade. The school has one teacher and one aide, according to an official with the Bayfield School District.

A recent report by National Public Radio indicates there were 190,000 one-room public schools in the U.S. in 1919, compared to about 400 today. More than 75% of the remaining one-room public schools are in the states of Nebraska, Montana, South Dakota, California and Wyoming.

Apps says the general rule of thumb during the one-room school heyday was that no family should be more than 2 miles from a country school. That’s because most students walked to school, and a walking distance of more than 2 miles was considered prohibitive. Thus, school districts were small, with schools in the middle and students congregating from 2 miles in every direction.

Vivid memories

Apps started first grade two months after he turned 5, but he remembers standing at the end of his driveway at the age of 3, watching the other kids walk by on the way to school. It was a big deal when he could finally join them.

“I remember the first time walking to school with the bigger kids, and at the top of the hill, with the school in the valley, Mike Korleski stopped and said, ‘Just listen now,’” Apps says. “He must have had a watch — something I never had — because at 8:30 the bell rang, ding, dong, ding, dong. That meant we had a half-hour to get to school. I’ve never forgotten that — the bell echoing down through the valley.”

Inside the school, youngsters from grades one through eight gathered to start their school day. At some grade levels there was only one student — that was the case with Apps — while in others, there were three or four. School enrollment generally varied from 15 to 30 students, depending on the year.

FUTURE AUTHOR: Students in the Chain-O-Lake School in Waushara County, Wis., posed for a photo in 1945. Apps is on the left in the second row, pictured as a seventh grader. (Courtesy of “One-Room Country Schools: History and Recollections.”)

The teacher handled everything in the building, from keeping the wood stove burning to handling janitorial duties to overseeing recreational activities and serving as the school nurse.

And of course, she (the vast majority were single women — a woman couldn’t be a teacher after she was married) was responsible for teaching arithmetic, reading, spelling, geography and history.

“When your class was called up to the front, all the other kids listened in,” Apps recalls. “You in effect got seven or eight years of the same subject. I was alone in my class for almost eight years, so the teacher would have me in second grade reading or fourth grade math, depending on where she felt I was learning.

“The parents and teachers were in cahoots with each other,” he adds. “If you acted up in school, you were in more trouble when you got home than you were at school.”

The kids disciplined themselves in some ways, Apps says. One of the rules of a snowball fight, for example, was you never hit a schoolmate in the face.

“I remember a time when one kid hit another kid in the face with a snowball and the rest of the kids grabbed the guy who threw the snowball, threw him down and washed his face with snow,” he says. “He never did that again.”

The good ol’ days

Apps got a new cap when he began school at age 5, and he recalls one of the bigger kids swiping the cap off his head while they were carrying kindling in for the wood stove.

“I picked up a piece of kindling, whopped him over the head and knocked him to the ground,” he says. “I got my cap back and he never touched me again. The teacher never found out, either.”

Apps remembers one of the six teachers during his eight years in the country school saying she wanted it so quiet in the building that everyone could hear the clock ticking on the wall. “And we could hear it — tick-tock, tick-tock,” he says.

Apps recalls filing outside at the beginning of the school day, where two eighth graders would raise the flag before all the students recited the Pledge of Allegiance together.

“When you were in first grade, your duty was to clap erasers to get the dust out of them,” Apps says. “The most advanced duty was raising the flag. In between there was sweeping out the outhouses, carrying in wood and water, and several other things. The teacher had us believing it was something to be proud of when we graduated to sweeping out the outhouses as compared to clapping the erasers.”

RHINELANDER SCHOOL: A 100-plus-year-old one-room school from the Rhinelander area was moved to Pioneer Park Historical Complex in Rhinelander, Wis., in 1976. The school building is full of information and artifacts used to teach visitors about early American rural schools back when chalkboards, well pumps and walking to school uphill both ways was the order of the day. (Courtesy of Susan Apps-Bodilly)

About midmorning the students would all race out of the building for recess. There were games such as Ante-I-Over, which consisted in part in throwing a ball over the school building, and Pom-Pom-Pullaway, a version of the old-fashioned game of tag.

Softball was also a favorite sport at virtually all country schools, Apps says. At his school, first base was a boxelder tree, second base was a black oak tree, and third base was a white oak tree. The backstop for home was the side of the outhouse. The outfield was full of trees.

“We had a special rule called the rule of the tree. If someone clobbered the ball and it got stuck in a tree, we waited for it to come down, caught the ball, and the player was out. We had to be patient,” Apps recalls.

The school never closed during inclement weather, Apps says, even if it was 35 below zero. Many schools were heated with a single wood stove, while others had a coal-burning furnace in the basement.

“On those cold days, the teacher would get there a little bit early to get the wood stove going,” he says. “Our school building was not insulated and there were no storm windows. The front end of the school was so cold you couldn’t stand it. We had a wind-up Victrola record player, and one of our teachers would put a John Phillips Sousa record on and we would march around inside the school to get warm. We would have all of our class sessions around the stove because it was so goldarned cold.”

DODGEVILLE SCHOOL: The Floyd School, which was built in 1886 and was used as a school until 1961, was located north of Dodgeville, Wis., near Gov. Dodge State Park. The Iowa County Historical Society acquired the country school in 2008 and moved it from its location on Floyd Road to the museum site on Dodgeville’s north side. (Jim Massey)

The school nurse came once a month and brought goiter pills for the students. The soil in the Great Lakes region does not contain much iodine, and iodine deficiency was the most common cause of goiters. A goiter is an enlargement of the thyroid, and the pills were designed to prevent it from occurring in the schoolchildren.

“They were so laced with chocolate that we liked them,” Apps says.

Polio was also a concern after World War II, and in fact, Apps was one of two children in his country school to contract the disease. The other student died, and it temporarily paralyzed Apps’ right leg.

“The Wild Rose Hospital was full of polio kids,” Apps says. “I’ll never forget the doctor saying to my mother and dad, ‘I think he has polio. Take him home, keep him warm, give him lots of fluids and keep him comfortable,’ meaning he’s not going to live very long.” He was 12 at the time.

Editor’s note: This is the first in a two-part series on one-room schools. In next month’s story: the end-of-year picnic, Christmas program, closing of one-room schools and more.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like