July 3, 2017

There is a line in the movie “Hoosiers,” loosely based on the 1954 Milan High School state champion basketball team, where Barbara Hershey in her role as a teacher tells Gene Hackman, the basketball coach at Hickory, “This town is so small, it’s not even listed on most state maps.”

That didn’t mean it wasn’t important. The mythical town of Hickory turned out to be very important to the local rural community, much like Milan was in real life.

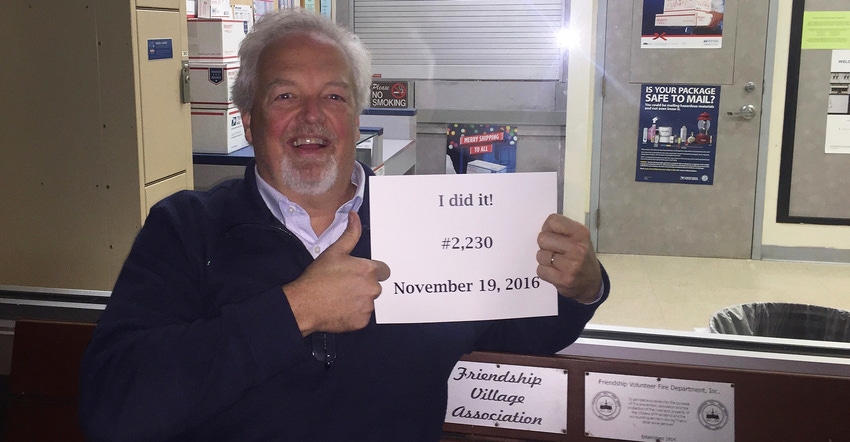

Phil Anderson, a Clinton County farm boy who later served as executive director of several state commodity groups, sees the importance of rural towns. He soon found himself staying off main highways during more than three decades of traveling Indiana.

“Some are just a crossroads today,” Anderson says. “I told a friend I was going to visit a town near him, and he looked puzzled. The name was on the map, but he had never heard of it. Today, it’s just a crossroads.”

A few places Anderson has tried to find don’t exist anymore. The name may still be on the map, but changes have occurred to the area.

Did Anderson learn anything as he wandered through more than 2,000 towns? “I soon began to wonder why some towns flourished and some didn’t,” he recalls. “Why did some towns make it and would-be towns just disappeared.”

Local leadership

Anderson soon focused on figuring out what happened to places that don’t exist anymore.

“Sometimes it was just circumstance,” he notes. “Maybe the town was built along the railroad and eventually the railroad wasn’t as important anymore.”

Sometimes, however, Anderson suspects a different factor was involved. “I’m guessing there was a lack of local leadership sometimes,” he says. “It can be one of the reasons why a place stops being a place.”

Anderson believes that rural Indiana needs leadership as much as any other type of community. He is sometimes asked to consult with local communities that are trying to put themselves back on the map. Often it’s by trying to attract people to come see a piece of history that might exist in the area.

“It’s tough to do by yourself,” Anderson says. “We’ve found it works better if you work with other communities who also want to attract people. Band together and tell people about what an entire area offers, not just one rural community. You may even want to create an official byway through the state.

“A byway is just a series of connecting roads that take people through various communities in an area or region. If you tell people everything of interest that is in that area, people will choose what they want to see. The more you can offer them, the more likely they’ll visit,” he explains.

Deciding to join with other communities in this effort is one form of leadership, Anderson says. Not everyone in rural areas sees such an effort as worthwhile.

The key is to work together and take advantage of what you have, he notes. That’s the best recipe for keeping your part of rural Indiana from becoming a name on a map that isn’t a place anymore, or even no longer a name on the map.

You May Also Like