October 24, 2018

It's a rare occasion when ag editors gets a chance to witness the opening of a museum exhibit dedicated to their publication and its founder. In mid-October, I had the opportunity to do just that with the ribbon-cutting ceremony for Brownville's Wheel Museum.

The Wheel Museum, formerly the McInnich and Kerns Ford Garage, includes an exhibit dedicated to Robert W. Furnas and the publications he founded, which includes Nebraska Farmer.

But Furnas, as Nebraska Farmer's first editor, did so much more. He was Nebraska's second governor, helped found the State Board of Agriculture and the State Historical Society, served as Nebraska's commissioner of agriculture, and helped promote and expand Nebraska agriculture in a number of other ways.

So, I was humbled when asked to give opening remarks before the ribbon-cutting ceremony in October. Of course, my small contributions pale in comparison to folks like Furnas or Sam McKelvie, but I'd like to think the work we're doing at Nebraska Farmer is useful to our state's farmers and ranchers in some way.

When Furnas first stepped off the ferry on Nebraska's eastern shore in Brownville in the 1850s, the Nebraska Territory — which included the expanse of land from the Nebraska-Kansas line to the Canadian border, and from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains — was home to just 25,000 people. At the time, the largest population center in the territory was Nebraska City — with 1,900 people, compared to Omaha's 1,800.

Although it was probably apparent even then that Nebraska would one day become an agricultural powerhouse, in those early days, Nebraska was not yet known as the Cornhusker State, the Beef State or the Irrigation State. In a sense, we were still finding our identity in the ag world.

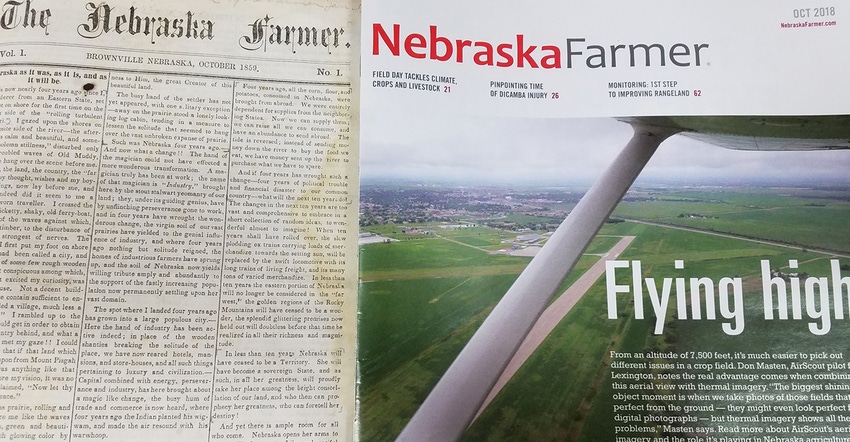

Maybe that's why, when Furnas published the first Nebraska Farmer in October 1859, the issue largely focused on correspondence between farmers. The goal was to figure out not only what practices worked for growers in different parts of the territory, but what varieties of crops and breeds of livestock were the most productive and most profitable.

One thing that always surprises people is the diversity of agriculture in Nebraska. That diversity is reflected strongly in those early issues. Southeast Nebraska was a prominent fruit belt in the 1800s, although there are still a number of commercial orchards and vineyards in the region today.

So, many articles in the 1800s focused on growing grapes, cherries and apples in the southeast Nebraska's continental climate and fertile, loess soils. With answers to questions like: Should I plant cherries in fall or spring? How should I prepare the seed bed? What grapes cultivars should I grow? Hartford Prolific, Diana, Delaware, Herbemont?

Of course, correspondents wrote about corn, wheat, sorghum, sugarbeets and potatoes, too, but this gives a good example of Nebraska's agricultural diversity and how farmers shared information. This agricultural diversity is also highlighted throughout the Wheel Museum.

According to Nebraska Farmer's 100th Anniversary issue in 1959, Furnas is quoted, "We hope, now that a medium is presented through which the farmers of Nebraska can communicate the results of their efforts, there will be no backwardness on their part to make a proper use of the Farmer columns. This is what we need, the experiences of those who have been cultivating our own soil."

Furnas may not have been editor of Nebraska Farmer for very long, but his work with the publication and with the State Board of Agriculture has had a long-lasting impact. One hundred years down the road, I hope readers will be able to look back at the content we're putting out now, and have a good understanding of where Nebraska agriculture is heading, and what farmers and ranchers are doing to sustain their operations for future generations.

You May Also Like