The typical cow-calf production system has largely remained unchanged for many years, but with lack of available pasture in parts of the Midwest, some producers are expanding their cow herds using a different method. That was the theme of the Cow-Calf Symposium held in March in Columbus by the Alliance for the Future of Agriculture in Nebraska (A-FAN), where four producers and consultants participated in a panel discussion to talk about their experience raising pairs in a hoop building or drylot.

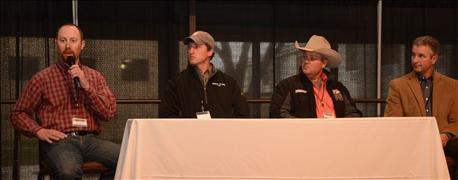

LEARNING CURVE: (Left to right) Jason Warner, Daryl Crook, Tyler Burkey, and Robert Eizmendi discuss raising cow-calf pairs in a controlled environment. Producers are constantly learning new things about this production system, but all panelists agreed: raising pairs in an enclosed environment takes a different, more intensive style of management. "Do your homework. Don't go into this haphazardly," says Warner. "Whether you think this is right for you, really pencil the numbers, I think that will save a lot of time, a lot of headaches."

Using these systems is what Jason Warner, nutritionist at Great Plains Livestock Consulting, Inc., refers to as a "continued learning process." "You never know everything you need to at the time you need to make a decision," Warner says. "It's one of those things where as you get more experience with the system, you gain more confidence in how the system is working."

Use your resources, environment

"What led us to what we're doing is we wanted to grow," says Tyler Burkey, who raises cow-calf pairs in hoop buildings on his farm near Milford. "We said, 'How can we be more efficient? How can we use the resources we've got?'" That's the question asked by many producers who are interested in these systems, and the environment and resources available differ for every operation.

Where Daryl Crook raises cow-calf pairs in a hoop building near Rising City, there is plenty of corn, corn stalks, and co-products available for feed. Meanwhile, for Burkey, it's all about low-cost fiber – rather than chopping silage, he's chopping triticale, ryelage, or other crops that are planted as cover crops, adding to the conservation component with manure.

ROOM TO GROW: Tyler Burkey guides visitors on a tour of one of his cow-calf hoop buildings. "What led us to what we're doing is we wanted to grow," says Burkey. "We said, 'How can we be more efficient? How can we use the resources we've got?'"

In eastern Nebraska, producers have to contend with moisture. So, one critical factor is keeping cattle dry, says Crook. This means managing air flow and using enough bedding to keep calves dry – especially right after calving. "Dry is your friend in these barns – it's not a warm barn, it's a dry barn," says Crook. "When you're looking at the site preparation, you've got to have air flow going through the barn."

~~~PAGE_BREAK_HERE~~~

In the Midwest, there are plenty of cornstalks available for bedding. While new bedding needs to be provided more often depending on the season to keep cattle dry, manure and bed pack is typically cleaned out twice a year, allowing producers to apply it back on crops as fertilizer.

AVAILABLE RESOURCES: The environment and resources available differ for every operation. Where Daryl Crook raises cow-calf pairs in a hoop building near Rising City, there is plenty of corn, corn stalks, and co-products available for feed. For Tyler Burkey, (whose barn is pictured) it's all about low-cost fiber – that is, chopping triticale, ryelage, or other cover crops.

For Roberto Eizmendi, general manager of Cactus Feeders' cow-calf facility in Syracuse, Kan., being in a semi-arid environment is ideal for raising pairs outside in a drylot, and bedding isn't necessary. When bedding gets wet and is left idle, it ferments and becomes a breeding ground for bacteria. "In a hoop system or a monoslope barn where you have a high concentration of cattle, it's easier to put in and remove bedding compared to a larger environment like us where we have 700 to 800 square feet per cow," Eizmendi says.

A different management style

A controlled system takes a different approach to management, especially when it comes to nutrition and herd health. Some, like Crook and Eizmendi, limit-feed cattle to make sure wastage is minimized and cater to specific needs of cows and calves in each pen. Others, like Burkey have left the traditional bunk system for a curb system similar to a dairy facility.

Being in a controlled environment means there are fewer stresses, and when stresses are minimized, nutritional requirements are lower.

But these systems also require following proper health protocol – giving the proper vaccinations to heifers, cows and calves to protect against viral and bacterial diseases, with the overall goal of building immunity levels in colostrum. "In this kind of system, you are more concentrated, you have more bacteria, and you need to build your immunity," says Eizmendi.

Producers are constantly learning new things about this production system, but all panelists agreed: raising pairs in an enclosed environment takes a different, more intensive style of management. "Do your homework. Don't go into this haphazardly," says Warner. "Whether you think this is right for you, really pencil the numbers, I think that will save a lot of time, a lot of headaches."

Learn more in an upcoming print issue of Nebraska Farmer.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like