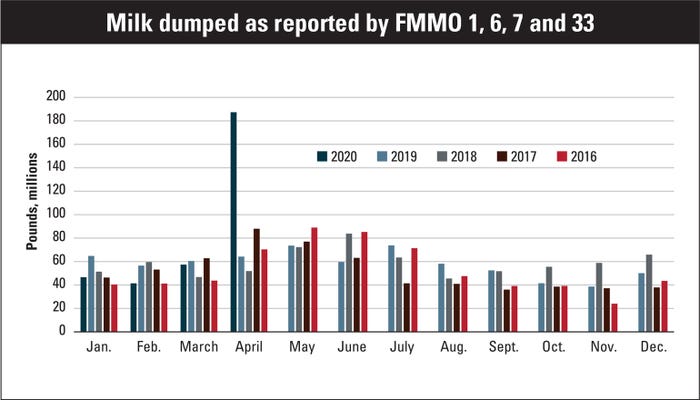

Dumping milk is not a new thing. In fact, four Federal Milk Marketing Orders reported dumping 40 million pounds of milk in January and February, and another 60 million pounds in March.

But April was different. The closure of restaurants and schools and the inability of the dairy supply chain to move product led to more than 180 million pounds, or 22 million gallons, of milk to be dumped in these four orders, according to data from CoBank, which looked at amounts of milk being used for animal feed or disposed of from the Northeast, Mideast, Southeast and Florida milk marketing orders.

Collectively, these four orders account for 55% of the U.S. milk supply, according to Amanda Durow, vice president and dairy specialist with CoBank.

The Northeast alone reported 15 million gallons of milk dumped, the highest of the four orders.

Durow said that milk is dumped at some levels each year because of production seasonality and limitations on processing plants. Dumping is usually highest from April to June when the spring flush occurs.

But the fact that the COVID-19 crisis hit just as spring flush was kicking into gear exacerbated an already difficult situation for farmers.

Now that things have settled a bit, the industry is assessing where it goes next.

Three farmers — Ben Gingg of Triple G Dairy in Buckeye, Ariz.; Greg Sabolik of Bred and Butter Dairy in Kensington, Minn.; and John Knopf of Fa-Ba Dairy Farm in Canandaigua, N.Y. — talked about how the COVID-19 crisis is affecting their farms and how the industry should go forward during a recent webinar.

Gingg, owner of Triple G Dairy in Buckeye, Ariz., a 4,000-cow dairy and crop farming operation, had to cut milk production by 10%.

“We’re one of the areas that dumped a lot of milk,” he said. His farm is part of a large dairy cooperative in Arizona where farms average around 2,500 head.

How did he cut back? He went from three times daily milking to twice daily milkings in a rotary parlor, and he also culled cows. He also modified the feed rations to cut back on production.

“We had quite a few things we had to do to cut back milk,” he said, adding that close to 20 million pounds were dumped by the cooperative in April.

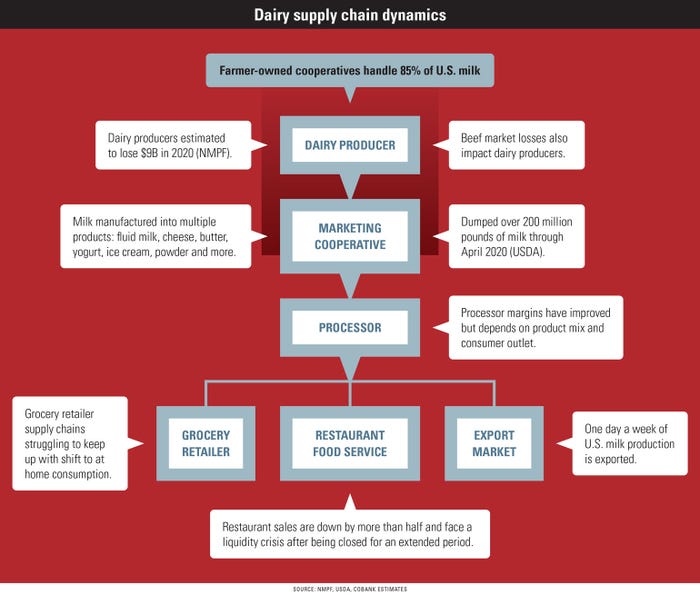

The fact that restaurants have started opening back up has helped the situation somewhat, but the big bottleneck was the cutback in cheese production by the co-op’s cheese customer.

“It meant a lot of milk on our hands that couldn’t get run through a dryer,” he said.

Many dairy farmers across the Northeast dumped milk, but John Knopf, who farms 30 minutes south of Rochester, N.Y., and has 575 cows and 800 acres, was lucky. His milk cooperative anticipated market needs and aligned production with consumer demand.

“They’ve been able to manage. We have not had to dump any milk. We don’t have any production controls right now,” he said. “We’ve gotten through this a lot better than my friends and neighbors who are sending milk to other channels.”

Sabolik, a partner in Bred and Butter Dairy — a 500-cow dairy and 1,600-acre crop farm — was also lucky that his cooperative didn’t have to dump milk.

The CEO of the co-op, Sabolik said, was proactive in communicating with members about excess production and the effects of COVID-19.

“So that was very much appreciated. There was never a formal ask to voluntary cut back. We’ve come out of this fairly unscathed economically,” he said.

Adjusting to the 'new normal'

Sabolik said that his employees must wear masks and are encouraged to take other precautions, such as washing hands and using hand sanitizer.

The fact that the industry wasn’t nimble enough to move excess product from schools and other institutions to grocery stores and places where it was needed was a problem, he said.

“No farmer ever wants to see any food wasted, regardless of whether we are getting paid or not,” he said.

Asking dairies to cut back on production hits farmers hard, he said, since expenses largely stay the same. It makes running a dairy farm difficult and unprofitable.

Knopf said he thinks it will take a couple of years for foodservice and institutional sales to recover. In the meantime, he thinks processors need to rethink their supply chains in order to meet consumer needs and better respond to a crisis in the future.

“This is going to have a long tail. The dairy industry isn’t going to go away, but it will certainly look a lot different. Retooling and innovation is needed,” he said.

Gingg said that he isn’t so sure what the “new normal” will look like, but there has clearly been a shift from foodservice to retail.

With only one dairy cooperative in Arizona, though, it’s a delicate thing to balance. He said the cooperative is opening a dairy plant soon that will produce more fluid and allow the cooperative to shift sales from Class IV, the lowest paying price, and help balance their supply chains.

Enough government help

Knopf said that he appreciates the government’s rollout of programs such as the Payroll Protection Plan and the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program. But he thinks enough is enough.

“I think it’s enough. I worry about distorting market signals. We’re in a commodity business, and price is the only tool out there to balance supply and demand,” he said.

Gingg said that labor is a continuing issue where he’s located. Being close to Mexico, he’s been able to get workers through the TN Nafta Professionals visa program. But it’s been a struggle getting workers back as the workers must return home every year and get a renewal. It’s been made more difficult with the COVID-19 pandemic.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like