August 20, 2020

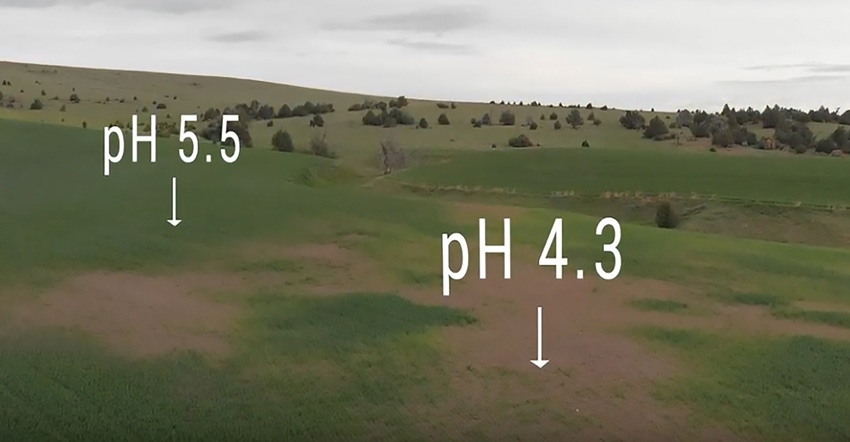

Montana crop producers could be facing a mystery yield problem that’s showing up in bare spots in the middle of what appears to be a healthy crop. The problem is the changing pH of the soil, transforming productive land into barren soil.

Clain Jones offers insight in a new video from Montana State University. Jones is MSU Extension's soil fertility specialist and a professor in the MSU College of Agriculture’s Department of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences. “Soil acidification is an emerging issue in Montana, where low soil pH has traditionally not been a concern,” Jones says. He adds that pH levels low enough to harm crop growth have been found in 24 Montana counties. You can view the video at the end of this story.

To help farmers solve the issue, the university’s new informational video shows the impact of the problem and offers management options. Produced by Jones and Nate Kenney, a graduate student in MSU’s Science and Natural History Filmmaking program in the School of Film and Photography, the video features Brent Hanford, a Fort Benton, Mont., farmer collaborating with MSU on the issue.

Digging in on pH

Acidity is measured on the pH scale, with numbers from 0 to 14, with lower numbers being more acidic. Jones notes when soil pH falls below 6, legumes have trouble fixing nitrogen, which supports growth and development. That soil acidity can also change herbicide action, affecting how long herbicide residue stays active in the soil. If the soil pH drops below 5, aluminum that exists naturally in the soil can be released — which, when taken up by plants, can damage your crop.

Research by MSU soils professor Rick Engel, Jones and others shows that ammonium fertilizers, including urea, are the major cause of soil acidification in agricultural soils. Acidification can be hard to detect, since it can begin in a small area or be isolated to particular soil depths. The standard soil test might miss those acidic areas, making detection more difficult, Jones notes.

Soils tend to become acidic fairly quickly, even with the recommended levels of fertilizer use. “This means it’s not a question of if, but when, this problem will affect a specific cropped or fertilized field,” Jones adds.

Taking action

Liming and manure applications are primary long-term fixes for acidic soil, Jones says. This also allows continued production of crops. When using spent sugarbeet lime, this can cost about $100 per acre with hauling and application costs, but can provide a 15- to 20-year benefit.

Selecting crops that use less nitrogen — including legumes, perennial grass and barley — and applying nitrogen fertilizer in ways that maximize the amount taken up by plans can slow that downward pH slide, Jones says. He adds that some crops and varieties are more tolerant of low pH, and perennials may slowing increase soil pH.

Engel’s research, funded by the Montana Fertilizer Advisory Committee and a USDA Western Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education grant, also found that seed-placed phosphorus fertilizer can help crops tolerate high soil aluminum levels caused by low pH. But this is a short-term adaptation, not a long-term solution, Jones says.

Source: Montana State University. The source is solely responsible for the information provided and is wholly owned by the source. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like