Surface water irrigators in western Nebraska and eastern Wyoming had their water supply cut off this summer when a tunnel used to convey water for the Goshen Irrigation District and Gering-Fort Laramie Irrigation District experienced a partial collapse, causing a backup of water in the main canal and a breach in the canal bank near Fort Laramie, Wyo.

At the moment, there’s only speculation as to why the tunnel collapsed. Gary Stone, Nebraska Extension educator in the Panhandle, notes the tunnel was built in 1917 — more than 100 years ago.

It was built about 2,200 feet long with about 2 feet of drop over that distance, and about 14 feet in diameter.

“Now there’s a gap between the outer wall of the concrete and inner wall of the substrate,” Stone explains. “The geology of substrate is sandstone, Brule clay and sand. Over the years, water could have leaked down in the cavity, eroded the top of the tunnel and eroded the cavity out. Eventually, the cavity got so big it couldn’t hold itself up and punched two holes in the tunnel. They estimate there are about 5,000 cubic feet of sediment that went through the tunnel.”

Citing information from the Goshen Irrigation District and the Gering-Fort Laramie Irrigation District, Stone notes at the time the tunnel collapsed, the canal was flowing at about 1,325 cubic feet per second. “That’s about 595,000 gallons of water flowing per minute,” he says.

The irrigation districts hope to have water flowing to the ditch by sometime in mid-to-late August. After that, it will take another five days for water to reach the end of the ditch in Nebraska.

Until then, Gering-Fort Laramie Irrigation District and the Goshen Irrigation District are working around the clock from both ends of the tunnel. The process involves drilling holes around the diameter of the tunnel and pumping a foam-like additive into the holes to fill the cavity space.

“Until they hit the breach in the tunnel, they don’t know what they’re going to find. And they don’t know how they’re going to patch it until they get there,” Stone says.

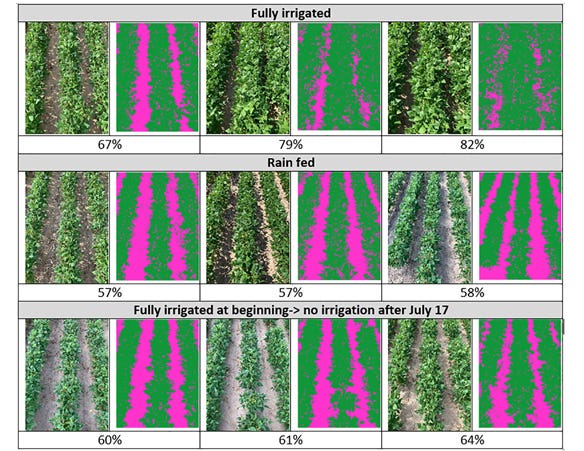

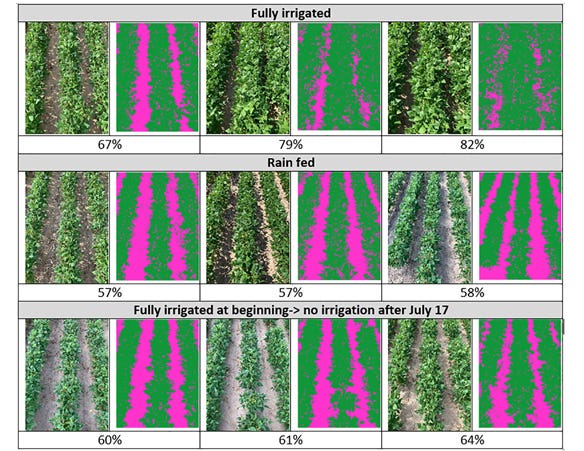

DRIED UP: These photos, taken July 30, show the effect on a plot of dry edible beans at the Panhandle Research and Extension Center after receiving no water since July 17 to simulate the effect of the tunnel collapse in eastern Wyoming and western Nebraska.

Jessica Groskopf, Nebraska Extension agricultural economist in the Panhandle, notes about 107,000 acres are affected — including about 55,000 in Nebraska and 52,000 in Wyoming.

While the exact crop mix isn’t known, there are about 2,700 acres of sugarbeets and 20,000 acres of dry edible beans. The rest that would be irrigated would be a mix of corn and alfalfa.

With the corn at varying growth stages at the time the water was cut off — most of it hadn’t tasseled yet — it’s hard to say what the economic impact will be. If the area receives enough rainfall, the corn may tassel and produce an ear. Also, sugarbeets have the greatest likelihood for survival because of their deep roots, early planting and earlier canopy.

The crop that will take the biggest hit likely will be dry edible beans. As a legume, dry beans will abort their flowers and won’t form a pod if they don’t have water.

“The good news about dry beans is contracts on them have Act of God clauses, so there isn’t guaranteed delivery,” Groskopf says. “For corn, if growers cash-forward contracted to an elevator, they’re going to have to do a bushel buyback or find someone to deliver corn for them. If producers were more aggressive in cash-forward contracting and guaranteed delivery, I don’t know how elevators will handle it. Some will dismiss it, but usually those are guaranteed bushel delivery.”

At this point, it’s still uncertain whether crop insurance will cover losses, Groskopf adds.

“Insurance covers irrigation failure by natural causes, but we don’t know if this will be determined a natural or man-made cause,” she says. “If it is covered by insurance, they have to take that crop to harvest and use best management practices and prove they maintained the crop to the best of their ability. That can be a struggle. They also need to take crop progress pictures and notes about management for insurance purposes.”

In the meantime, Xin Qiao, Nebraska Extension irrigation specialist in the Panhandle, is simulating crop loss due to water stress by cutting off water to corn, sugarbeets and dry edible beans in plots at the Panhandle Research and Extension Center at Scottsbluff, Neb. He’s also using soil moisture probes and cameras to track crop stress and crop water use.

“After the incident, we cut off water on those plots to see what’s going to happen,” Qiao says. “What we’re tracking is canopy cover on a weekly basis, and we haven’t seen much difference on corn and sugarbeets yet, but we’re seeing a lot of difference on dry edible beans.”

The governors of Wyoming and Nebraska have issued emergency declarations to direct state resources to the area and are helping coordinate recovery efforts.

The University of Nebraska and University of Wyoming are assisting producers and providing resources on concerns relating to production and financial and mental well-being that arise with these kinds of scenarios. To learn about these resources, visit extension.unl.edu.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like