February 1, 2019

Keeping soil covered is an idea you may be hearing more about as growers discover the range of benefits offered by cover crops. From improving soil health to trapping insect pests, from improving weed management to providing livestock forage, cover crops create new opportunities.

There are several factors to determine which plant species of cover crops are suitable for your operation. Consider the climate and growing season length for your area, and then assess the windows available between crops.

“[Here in southern Idaho], many farmers grow dry beans or peas harvested for seed,” explains Glenn Shewmaker, professor of plant sciences at the University of Idaho Kimberly Research and Extension Center, Kimberly, Idaho. “These can be seeded with a cover crop in late August or early September, so it’s possible to grow a second crop in that 60- to-70-day window.”

For a 60- to 70-day growing beginning in August, warm-season crops may be suitable. If you want to graze livestock on a forage cover crop the following spring, cool-season cereal grains — such as oats, barley or triticale — work well.

With cover crops, it is important to plan termination, so it doesn’t impact your main crop. “You don’t want the cover crop to produce seed,” cautions Roger Hybner, research associate at Montana State University’s Northern Agriculture Research Center, Havre. “You’ve got to terminate it — by grazing, swathing or chemical application — as soon as possible after the seeds head out.”

Crops for alternative grazing

Grazing livestock on the cover crop is the most beneficial termination for soil improvement and farm profit. Cattle will eat legume, cereal, oilseed, and brassica (root) crops. “To train cattle to dig for the roots of a brassica crop, such as turnips and rutabagas,” Shewmaker explains, “it might take some tillage to uncover the roots. Once they learn, cattle will mud around with their nose to eat them.”

Brassica crops have tiny seeds. To prevent crop failure, carefully prepare the seedbed, your drill depth and irrigation application amounts. Brassicas do not dry down enough to bale for forage, but they can produce high amounts of dry matter for grazing. Livestock need to be intensively managed to graze efficiently, such as by moving electric fencing for strip grazing. This also uses livestock to spread manure evenly and tramp the cover crop plant residue into the soil.

“Grazing reduces the total amount of [plant] residue,” says Shewmaker, “to where minimum tillage or strip tillage is more effective [at soil preparation for the main crop] than if the entire cover crop residue is there. The animals do reduce the amount of the plant fiber left from the cover crop, albeit it’s returned to the soil in cow pie form.”

Helping the soil

Hybner says that cover crop mixes with legumes will add from 10 to 20 pounds of nitrogen to the soil. Crops won’t benefit from this fertilizer until the following year, because it takes several months for the legume plants’ nodules to decompose.

Cover crops also prevent wind and water erosion of the soil and reduce evaporation of moisture from the soil during the fallow period between your main crops. “The cover crop does use some of the soil moisture,” Hybner acknowledges. “But, if you terminate it right at, or before, heading, the late-summer and fall rains should replenish the moisture in the soil profile. Then, as in Montana, you are able to plant a winter wheat crop that fall or a spring wheat the next year.”

Trap crops

The wheat stem sawfly is a major pest in Montana wheat fields. Planting oats controls sawflies, because the insects lay their eggs in oat plants, which contain a chemical lethal to sawfly eggs. If you don’t want to plant a cover crop of 100% or mixed oats, Hybner recommends planting an 8-foot buffer of oats around your wheat fields to reduce sawflies.

Brassica crops also trap certain pests. Their roots penetrate the soil and disturb underground pest colonies. For successful pest control, Shewmaker says, “It’s important to till and roll over the brassica roots to break the green bridge.”

A “green bridge” transfers pests and diseases between crops, because green plant matter moves inoculum from one crop to the next. “The green bridge is a disadvantage of cover crops, because planting crops in close succession eliminates long periods of fallowness for the soil,” Shewmaker says. “Producers should leave a field without green, living plants for at least two weeks between crops.”

Choose by location

For your cover crop’s success, select a seed mix that suits your climate and soil. For instance, in Montana there is a natural soil disease that wipes out chickling vetch — a common cover crop in other areas. Research at the Northern Ag Research Center in Havre has shown that navy beans, fava beans and chickpeas work well. Hybner also experimented with kidney beans, but their large seed size can plug up the seeding drill.

“Some cover crop mixes use exotics, like mung beans, that are expensive,” Hybner says. “To avoid using exotics, you can go to bean elevators and purchase their surplus seed at a greatly discounted price.”

Hybner says there isn’t a generic cover crop mix that works for everyone. For instance, in northern Montana, if warm-season annuals are planted in mid-May, they need to have adequate moisture in the seedbed for establishment and growth — especially if a dry June and July are forecasted. Montana State University research shows that cool-season cover crops generally produce more in the state.

No matter where you live, cover crops can be a challenge, because every year the weather is slightly different. “It is hard to select cover crops that deliver both yield and quality according to the expected weather,” Shewmaker says. “I think the cereal grains are the most reliable. Brassicas sometimes do well, and other times they fail. But, if we get a warm summer in southern Idaho, it’s hard to beat the yield of brassicas.”

Both Shewmaker and Hybner recommend choosing your cover crop based on your goals, which may include supplemental livestock grazing, micronutrient cycling in the soil and/or increasing organic plant matter residue. Then, find cover crop mixes that suit your goals and your climate. Most land-grant universities support ag research centers that test plant species for cover crops, and a mix may already be developed for your needs.

“For example, in southern Idaho, we would know that eastern Oregon or northern Utah are similar in growing climate,” Shewmaker explains. “We can take cover crop data from those areas and be reasonably assured that it applies here in southern Idaho.

“The biggest thing to remember about cover crops, whether you graze it or put it up as harvested forage,” Shewmaker continues, “is that it still requires management. You need to manage it just as you would any other crop. If you don’t, you risk that input cost, and you may not get a cover crop that pays for itself.”

TEST AND CHOOSE: This is a field of yield trials comparing brassicas, cereal grain forages, grazing corn, sorghum, legumes, and mixes. In the foreground is Washford beardless barley in a mix with purple-top turnips, with spring cereal forages above and to the left of the barley mix, and grazing corn to the right. (Photo by Glenn Shewmaker, MSU)

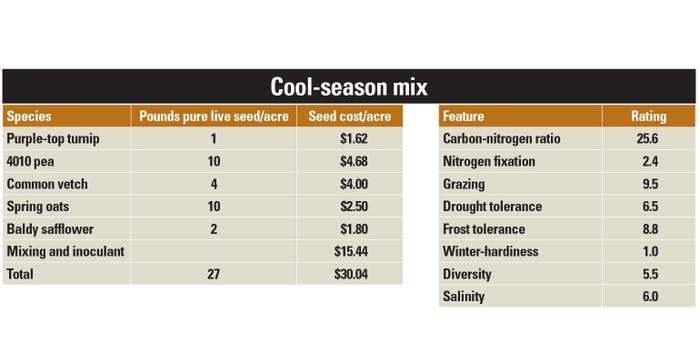

A look at 2 cover crop mixes

There are a lot of factors that can impact your cover crop choices. The main factor is the weather or timing for planting that crop. What follows is a look at two mixes — cool-season and warm-season — and their costs. Your local Extension agronomist can offer insight into mixes and approaches that might be better suited for your operation. Thinking cool, and grazing

Thinking cool, and grazing

If you’re looking for a cool-season mix that can be used for grazing as part of your termination plan, this mix in the table here offers some options.

Cover crop research at MSU Northern Ag Research Center in Havre shows a minimum of 24 to 30 pounds per acre of seed should be planted for the mix listed. Otherwise, there is too much bare soil. Costs are from the Green Cover Seed 2019 price list and do not include shipping costs. The carbon to nitrogen (CN) ratio is best around 24. The ratings in the tables other than the CN ratio (from nitrogen fixation to salinity) are on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the best.

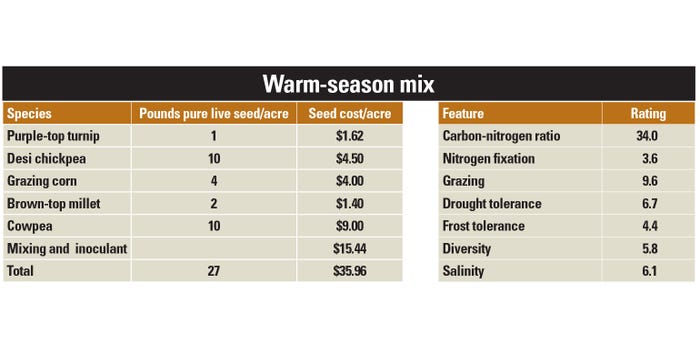

Warm-season mix

Warm-season mix

MSU Northern Ag Research Center plants this May 15 and begins to graze it Aug. 15. Costs are from the Green Cover Seed 2019 price list and do not include shipping costs.

Talking teff

MSU finds that teff, a warm-season annual, works well under irrigation near Bridger, Mont. Teff can be grazed and baled. It makes high-quality horse hay. “The problem with teff,” Hybner cautions, “is that it’s very, very small-seeded. There’s over a million seeds per pound. To seed it, your depth needs to be an eighth of an inch or less. It is an annual in Montana, because winter temperatures kill it.”

Hemken writes from Lander, Wyo.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like