It’s a Sunday evening in mid-October and southern Illinois pumpkin farmer Leon Adams is in a race against time — and frost.

There’s a freeze warning for Monday night, just 24 hours away. He’s harvested 370 acres. He’s got 30 to go. On Sunday evening, Adams is making a pallet run to the Frey Farms production center in Poseyville, Ind., about an hour from home, so everything will be ready for picking pumpkins at 7 a.m. the next morning.

“I don’t know that we’ll get ’em all picked by the frost tomorrow night,” Adams says. “That’s the risk in diversification.”

Several years ago, Adams was a corn and soybean farmer who wanted to diversify his business, but even more, he wanted to grow something that a consumer would touch. He’d grown up helping his grandpa cultivate blueberries on their Bonnie, Ill., farm. He loved it. And his entrepreneurial drive is hard to shut off.

“Those blueberries made people smile and made ’em happy,” Adams says. “Most people don’t get to experience the labor of love and toil to raise something like that. I wanted that again, but it had to make sense in the business.”

So he and his wife, Andrea, spent a few years researching what they could grow, in volume. They were too far from Mount Vernon, the nearest urban area, for agritourism. Their soil wasn’t suited for blueberries long term. They considered lavender, dairy goats and elderberries. But he kept coming back to pumpkins, and to a long-ago FFA visit.

Back when he was a section FFA officer, Adams visited Frey Farms, the near-legendary operation headed by Sarah Frey near Keenes, Ill. The Wayne County native started growing pumpkins and melons back in the ’90s, expanded, landed a Walmart distribution agreement, and is now the nation’s largest pumpkin grower, producing fruit and vegetables in seven states. Look around Walmart, Aldi, Kroger, Lowe’s and more this time of year, and you’ll see bins of Sarah’s Homegrown pumpkins. Frey Farms is also the largest H-2A visa employer in Illinois.

So Adams reached out to Frey Farms.

“We both found interest in each other,” he recalls, adding that he had to meet several benchmarks. He had to plant, maintain the crop, and have a warehouse to handle it. He needed to be able to handle 15 to 18 trucks a day for five days, with 60 bins of pumpkins per semi.

“They said, ‘Give it a try.’ So we did.”

In 2019, Adams raised 160 acres of pumpkins for the first time. He doubled to 300 acres in 2020, then expanded to 400 acres in ’21 and ’22.

His initial capital investment was sizable: new loading dock, bigger approach pads and concrete in his 60-by-140-foot machine shed, which meant he could convert it into a packing shed for two months out of the year.

“I also had to be OK with random semis sitting out in the farm and spending the night, helping people who don’t speak good English, and there’s the occasional truck that turns the corner and drops the trailer in the roadside ditch,” Adams says. “People, equipment and manpower — it all comes with struggle.”

And while Adams grows on contract for Frey Farms, there’s no delivery clause like you’d have on a corn or soybean contract. If he loses a crop — like the 25 acres of mini whites last year — he doesn’t have to go buy pumpkins to fill the contract. But he’s out thousands of dollars in seed, fungicide and other inputs. There’s no safety net, because federal crop insurance doesn’t kick in the way it does for grain crops.

“It’s not for the faint of heart to look at all the hundred different ways to kill your pumpkin crop,” Adams says. “If the weather takes you out, that’s it. You pick yourself up and do it again next time.”

The growing season

Adams is growing jack-o’-lanterns, mini oranges, mini whites, pie pumpkins and an autumn mix of gourds. Because the Freys have a wealth of growing experience, they gave Adams what he calls a “Harvard education on growing pumpkins.” He took that and added the liquid fertility programs he’d already developed for his row crops. The upshot? Pumpkins like it.

He plants full-season pumpkins behind soybeans, hopefully by mid-May. Then they plant everything else into wheat straw, which they’ve learned acts as a natural disease barrier. Adams’ goal is to have every seed in the ground by June 20.

He can cover a lot of acres — think 250 acres of pumpkin seeds in the ground in a day and a half — but it took some work to get to that point. Early on, Adams worked with Precision Planting to convert his corn planter for pumpkin seed, including software. He jokes that they didn’t exactly have to call in NASA or SpaceX, but they did have to dismantle the high-speed functions and put everything back together.

He’s slowing down planting on purpose: Pumpkin seed is nearly triple the cost of seed corn.

“It’s like planting bulk pennies!” says Adams, explaining that he slows down, stops the planter a lot and digs. “Every seed needs to be tucked into bed nicely and given the opportunity to grow.”

It’s another measure of the heightened risk with a high-input crop, and another set of numbers at the top of his head when a possible frost looms.

Once seedlings emerge, the pumpkin plants are off to the races. Within 10 days of green leaves poking through the wheat straw, the plants will achieve 75% ground coverage.

After that, it’s a matter of keeping the plants healthy and the fruit set clean. If Adams gets behind on managing disease or insects like powdery mildew or aphids — for example, if it rains for a couple of weeks when he needs to spray — he could lose 75% of his crop.

“We’ve mixed as many as nine different products into a spray tank — not exactly like corn and beans,” he says.

He controls weeds with a hooded sprayer or hand sprayer and has even brought in some of Frey Farms’ H-2A workers from Mexico to hand-hoe weeds.

Those folks come back for harvest, when 35 to 45 men will pick and pack all 400 acres by hand.

“The H-2A workers are an amazing group of young men who are hard-working, appreciative of the work. They’re here legally, they’re courteous and appreciative — I can’t say enough good things about them,” Adams says. “They want to work hard and make some money to take back home.”

Not risk averse

With a frost bearing down, Adams is philosophical about the corn and soybean side of his business, where it’s easy to mechanically harvest a crop, and where harvest weather won’t typically destroy the crop.

“Risk is absolutely substantially higher with pumpkins. High input, higher income,” he says. “You don’t have the safety net that we’re used to in the corn and bean world.”

Plus, it’s been dry; he hasn’t had a rain since Aug. 5. That reduces fruit size, which reduces his paycheck. The pumpkin market is also affected by the economy, as consumers may cut back on pumpkin purchases.

Still, Adams is bullish on pumpkins: “I enjoy the challenge, and the reward is still greater than the risk.” In a good year, his pumpkins will give him the same net return as a 300-bushel-per-acre cornfield. In a bad year, it might be less than a poor bean crop.

Last push

Back in the field on Monday, the men are picking. They’ve started at 7 a.m. every day since Thursday. All day, they pick, they pack, they ship. And on the day of the forecast frost, they’re hitting it hard right off the bat.

Adams wonders if they could pack 20 semiloads on this Monday. Fifteen is a good day, and to pack 15 semiloads, they need a semiload of cardboard bins and two semiloads of pallets. That’s three semis coming in and 15 going out. The goal is about one semiload of pumpkins per acre.

Adams and his dad debate ways to add more storage. They only have so much space in the machine shed-turned-packing shed. They could put sideboards on their gooseneck trailer and on a drop-deck trailer, pile on the pumpkins, and park them in a building.

“Those things would work, just to keep the frost off of ’em,” Adams says.

By the end of that day, they’ve got 20 acres picked, packed and tucked away from frost. Night falls. Temperatures don’t drop as far as they thought. The sun comes up on Tuesday morning. Relief. One more day.

“By God’s grace, we didn’t get a very bad frost at all,” Adams reports. “Ten acres to go, and we’re done.”

And everybody exhales. It’s a good day to be a southern Illinois pumpkin farmer.

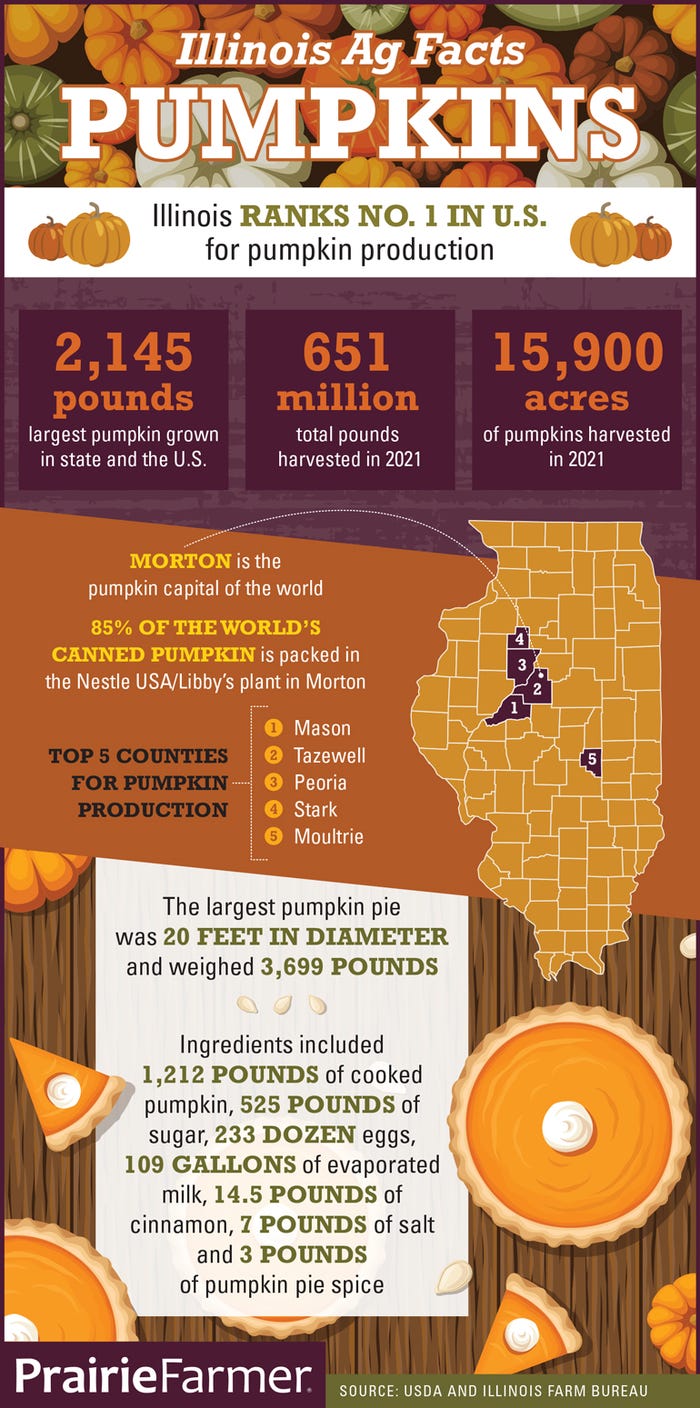

Check out the infographic below for more details on Illinois pumpkin production.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like