September 26, 2018

By John Duff

It is easy for those of us not taking financial risk to extol the virtues of forward contracting grain, buying options or selling futures. However, if you are a farmer, you have probably worried about not being able to deliver after guaranteeing bushels or taking futures positions. This is understandable. After all, farming is a risky business. But will failing to deliver cost you the farm?

To answer this question, I worked with a dryland farmer in southeast Colorado — one of the harshest environments in U.S. agriculture — to look backward at what would have happened if he had forward contracted his sorghum each spring for the past 30 years. His operation includes approximately 5,000 acres on which he typically plants about 1,500 acres of sorghum. His average yield over the past 30 years was 48 bushels. Therefore, his expected production each year is almost 74,000 bushels. To analyze the impacts of forward contracting, I assumed this farmer sold half of the expected production each year, or around 37,000 bushels, during April, May and June and sold the rest in November.

Why use these four months? Over the past 30 years, the December corn futures contract is an average $0.20 higher during April, May and June than it is in November. Therefore, an average of April, May and June futures prices is a good proxy for a favorable forward contract price, and an average of November futures prices is a good proxy for a harvest price. The results of this analysis were stunning. Had this farmer forward contracted 37,000 bushels each year, he would have failed to deliver all of his contracted bushels only four times in 30 years. This translates to a slim 13% chance of not delivering in one of the riskiest places to farm in the entire country.

Next, I examined these four years in a little more depth. None were total losses, and even in 2012 — the worst drought in this farmer’s career — he would have been able to deliver almost 20,000 bushels against the contract.

Furthermore, in three out of the four years, he would have made up for the shortfall the next year and then some, so rolling the contract forward would not have added significant risk.

Finally, I looked at profitability and found the farmer would have still been more profitable in two of the four years by capturing the higher price through forward contracting — even after buying the shortfall on the open market to fill the contract.

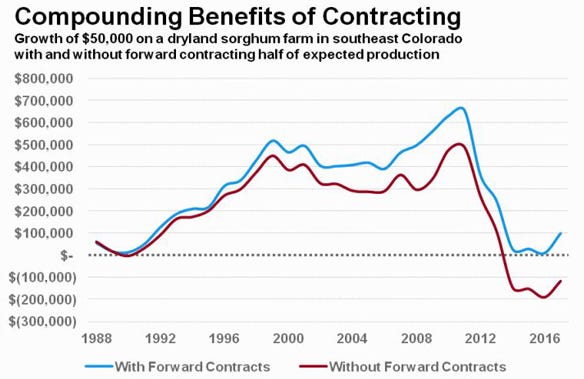

To conclude my analysis, I expanded the profitability study to cover the entire 30-year period, assuming the Colorado farmer started with $50,000 in 1988. The conventional wisdom often holds forward contracting and other marketing activities yield the same financial result over time but with lower volatility.

However, this would not have been the case for the southeast Colorado farmer. Had he started with $50,000 and committed to forward contracting half of his expected production each year, his $50,000 would be worth twice that amount today. Before the drought, his position would have been over $650,000. Contrast this with the result of selling everything at harvest every year and the compound effect of a commitment to forward contracting is clear.

With this scenario in mind, the answer to my initial question is that occasionally failing to deliver will not cost you the farm. In fact, the compound benefits of slightly more profitability each year will actually shield the farm from large losses. Keep in mind that southeast Colorado is a very harsh environment, and these are real numbers. I encourage you to keep fear from driving your marketing decisions. Embrace opportunities as they arise.

Duff is a strategic business director for National Sorghum Producers. He can be reached by email at [email protected] or find him on Twitter @sorghumduff.

You May Also Like