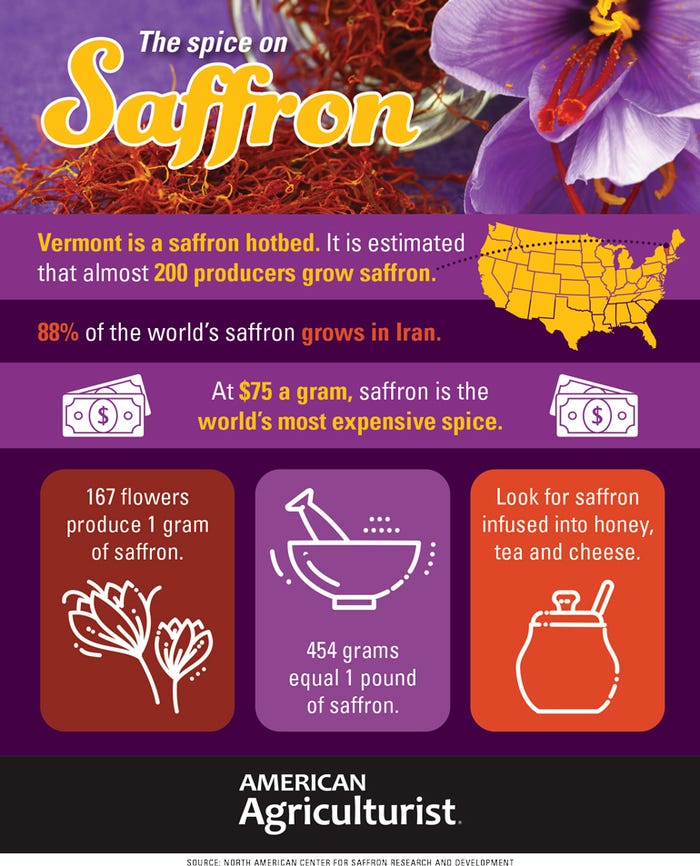

Selling for upward of $75 a gram — or $34,000 a pound — saffron is considered by many to be the world’s most expensive crop.

But should it be something you should try? Researchers in Vermont think it has potential, so long as you are patient and can handle the labor costs.

"To put it into perspective, the people who are selling for $75 to $85 a gram are getting more for their saffron than if they sold their gold earrings," said Margaret Skinner at this past year’s Mid-Atlantic Fruit and Vegetable Convention in Hershey, Pa.

Skinner is an entomologist with the University of Vermont’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, but she’s also become a well-known saffron expert. She co-founded the college’s North American Center for Saffron Research and Development, and has been talking to growers in the Green Mountain State and beyond about how to include saffron in their crop rotations.

What is saffron?

Saffron is a spice derived from the Crocus sativus flower, a perennial that multiplies in subsequent years after the initial planting.

Saffron doesn’t grow in summer — it’s dormant for most of June, July and August. It emerges in September and does all its growing within a month or two. Harvest occurs in about a two-week window in October, but it’s labor-intensive because each flower must be picked by hand, and the stigmas, which become the saffron, must be separated.

Skinner co-founded the center with Arash Ghalehgolabbehbahani, an adjunct professor in agroecology at University of Vermont, to become an information hub for anyone interested in growing the crop.

There is no official USDA or Vermont Agency of Agriculture data on the number of saffron growers in Vermont, but Ghalehgolabbehbahani estimates there are between 150 and 200 growers in the state based on conversations he’s had, and at least a few thousand nationwide.

Labor of love

Brian Leven, owner of the 10-acre Golden Thread Farm in Stowe, Vt., has been growing saffron since 2017. He bought his bulbs, or corms, from Roco Saffron in the Netherlands and planted them at the end of August. He built a small hoophouse, mixed some compost into the soil and planted a 3,000-square-foot bed.

His first harvest was small — only 15 grams. Since then, he has added a few more beds and another hoophouse. From the original corms he planted in 2017, they have multiplied each year, producing two to eight “daughter” corms that will produce flowers on their own.

It’s recommended the mother corms get dug out every four years, Leven says, as they can crowd each other out.

“And if they get too crowded, they’re going to be more exposed to pests and fungus,” he says.

Using a hoophouse, he says, minimizes weeds, which must be removed by hand. The plants are perennials and come back each year, but watering is important to break them out of dormancy, he says.

Other than weeding and watering, Leven says he does very little to maintain the crop. But once harvest begins, he must hire a few local teenagers to help pick the flowers and separate the stigmas. He even has his mother and a few friends help out.

The market for his saffron is his website where he charges $50 a gram.

Leven’s advice for growers? Start small.

“You have to really test and see if your setup is workable,” he says, adding that his biggest cost was getting the corms — which cost 30 cents apiece — and building the infrastructure for the planting.

Labor costs are why Melinda Price, co-owner of Peace and Plenty Farm in Lake County, Calif., the largest saffron grower in North America, doubts that saffron production will become scalable anytime soon.

The farm harvested 775,000 plants in 2021 from just a half-acre, and it sells saffron direct to consumers, wholesale, and even to stores and restaurants. They sell saffron-infused honey, teas and have an entire website dedicated to saffron-infused recipes.

The first planting and harvest was in 2017. “We saw what New England farmers were doing, and we were researching niche crops. We were stunned no one else was growing them commercially,” Price says.

But harvest season is busy. Twelve people are needed to harvest the half-acre plants twice a day, picking upward of 60,000 flowers a day. “It’s such a delicate plant that we need the human touch in there,” she says. “Some flowers are buried deep in the leaves. It’s time consuming.”

“We spend probably seven hours picking during peak harvest day. The rest of that 14-hour day, we’re separating the stigmas by hand,” Price adds.

Developing a market

Developing products from saffron has been key to her farm’s success, Price says.

Parker Shorey of Lemonfair Saffron Co., based in Brooklyn, N.Y., is trying to carve out a local market for saffron by partnering with a handful of Vermont farms to sell saffron direct to consumers and chefs.

Lemonfair primarily sells the dry saffron stigmas, but they’ve also created saffron pasta cream sauce, saffron olive oil and even infused honey. “We’d also like to get saffron candles going,” Shorey says.

Shorey grew saffron for two years, but transitioned to partnering with local farms to sell products as he thought it would allow for greater scale and specialization. “Farmers were figuring out how to grow it well, but we wanted to build the market for it,” he says.

Lemonfair markets organic saffron that’s finished over the low heat of a hardwood fire, a method used in colder saffron-growing regions such as Tuscany, Italy.

The company is small, Shorey says, as they take product from at most four farms per year — averaging 20 grams of product each — although at least one farm, Vermont’s Calabash Gardens, produces several hundred grams a year.

While the market for saffron is small, Shorey says there are reasons to be optimistic.

“One is the local, sustainable, organic movement. Spices have lagged the rest of agriculture, meaning you’ll get local crops but not spices, but that’s starting to change,” he says. “The other is just saffron for the U.S. is still being introduced, experimented with, studied, but I’m optimistic that it will become popular.”

Skinner is optimistic about its future, too.

“The future is its use as a value-added product, and what’s happening is more and more people are coming up with new ideas,” she says.

Know before you grow

Ready to grow saffron? Here’s some things you should know from Margaret Skinner, co-founder of the North American Center for Saffron Research and Development:

The bulbs, or corms, can be bought online for at least 25 cents each, although some websites sell them for up to $1 a piece.

The first corms are planted in August or September. Expect a light harvest the first year. The plants overwinter green, then start producing secondary corms the following spring before going dormant in late June. They will begin to flower again the following September with a bigger harvest expected. It is recommended the corms be dug out every four or five years.

Corms grow best in fine, sandy loam soils, but a well-drained soil is even more important to prevent flooding. A soil test is recommended, and the plant bed should be weeded and organic matter added.

The planting density is 6 to 12 corms per square foot, 6 inches deep. Skinner recommends starting small in a bed that’s 50 to 75 feet long.

It takes 167 flowers to make a gram of saffron.

It takes 17 minutes to pick 177 flowers and 34 minutes on average to separate the stigmas from the flowers.

Pick the flowers in the morning after dew has dried. Don't pick in the rain or snow. Separate the stigmas from the flowers right away. Dry the stigmas in an oven or dehydrator, or even a frying pan, at 200 degrees F.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like