April 7, 2017

It's not every day we get a call from a researcher in Africa with a good story. But recently, Farm Industry News was contacted by Dr. Joseph Ndunguru who works at the Mikocheni Agricultural Research Institute out of Cyprus. Based in Tanzania, Dr. Ndunguru is working on a project that's helping farmers in Africa beat diseases that plague cassava, a staple food for the region.

During a Skype call, Ndunguru explained that his work is targeted at managing key diseases like brown stem and mosaic virus that kill the plant and are often spread by planting diseased cuttings. His work is supported through the United States Agency for International Development and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. What caught our attention was the fact that his work uses some high-level tech for virus detection and identification in his fight against the plant diseases.

Cassava is a staple plant for the region and basically most of the plant can be consumed, the roots and leaves. Flour can be made from the roots as well. It is a key source of carbohydrates in sub-Saharan Africa, but it can also be susceptible to a range of diseases, which Ndunguru and his researchers are helping to solve.

"We are using molecular-based techniques and DNA to detect specific virus types," he explained. "And we're working with the viruses in the plant." The key is to not only identify the specific virus but perhaps the local strain of that virus.

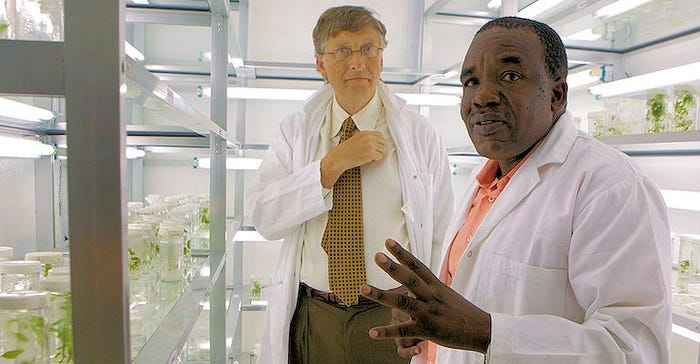

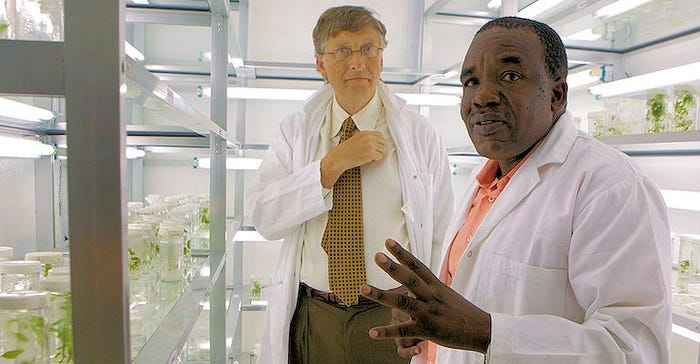

Dr. Joseph Ndunguru, foreground, talks about cassava viruses as Bill Gates looks on. Ndunguru's work is funded in part by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Cassava mosaic virus is often called the "curse" of food security in the region. Infected plants will not produce. The crop is planted from seedlings and if they're infected, the farmer won't know until later in the plant's life cycle. Essentially he would have planted a "dead" crop if it was already infected with the virus, or susceptible to infection in that region.

Ndunguru is working across the country to "type" the different CMV versions and mapping where they are. And it's important. "We have seen tremendous loss of production with mosaic virus," he said. "If you had infected plants you might get 5 tons per hectare, but uninfected plants in the same area would yield 50 tons per hectare." It's a devastating disease.

Tactics to beat the disease

Lack of knowledge is a big step to overcome as well. He explained that many farmers in the area aren't aware of the diseases, and will just plant root stock whether it's infected or not (and it most often is). "We're working to train farmers to identify the presence of the disease in plants that might be used for future crops," he explained. "Many don't understand that cutting diseased plants and using those cuttings can also spread the disease."

Through mapping, he has been able to identify which diseases flourish in which regions of the country. The idea is to move susceptible plant stock from an infected area for that type of the disease to an area where that disease doesn't exist. That way the plant can thrive because the disease isn't present. No fancy breeding, simply mapping disease susceptibility and changing the geography for the plant. Sounds simple, but identifying and mapping specific disease types by region takes a lot of work.

That "clean" stock is provided to farmers as a test or education opportunity. In the first year, test farmers would get one acre of plants that are targeted to a specific area where they're not susceptible to key diseases in the area. "This demonstration plot can show farmers in the area the potential yield of disease-free plants," he said. When those farmers see they can get 40 to 50 tons per hectare versus the anemic yields they saw with CMV-infected plants, they start paying attention.

Research assistants collect cassava samples as part of a project to help identify, and type, diseases for improved management of the crop.

The one-acre program can net 4,000 cuttings clear of virus for that area, which can be used to plant more acres and spread clean plants in a region. That first acre may be free as part of the program, but as the system grows farmers will have to buy the clean stock to expand their plantings.

And spreading that knowledge starts to pay off pretty quickly as farmer incomes start to rise with those higher yields. The training process is key and Ndunguru is engaging this by training farmers to recognize the symptoms of disease so they don't plant sick stock; bringing in the Extension workers in the region to learn to identify disease and work with others; and engage local governments in the process so everyone is working together.

With his work Ndunguru is showing that a little tech applied properly can be deployed to make a significant boost in productivity and small-holder farmer income. It's a tech story worth watching.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like