Just one Palmer amaranth plant has the potential to produce hundreds of thousands of seed. That’s why farmers in Preble County paid attention last July when agronomists from an area farm chemical company identified Palmer amaranth in one field between Eaton and Lewisburg. Farmers found the weed in several more fields, which had received manure from the same farm. Later, more of the weeds were discovered from two other sources elsewhere in the county, says Anna Smith, outreach coordinator for the Preble Soil and Water Conservation District. “If the first infestation hadn’t been discovered and created a lot of buzz, the second and third areas wouldn’t have been found," she says.

Palmer amaranth is a member of the pigweed family native to the southwestern United States. Once it infests a field it can spread rapidly because a single plant can produce hundreds of thousands of seeds, Smith notes. If it’s not controlled, it can drastically reduce crop yields, and controlling it can greatly increase herbicide costs. Most populations in Ohio are resistant to glyphosate and ALS inhibitors, and populations in the south have developed resistance to additional products.

While the first step to solving a problem might be recognizing that it exists, simply identifying Palmer amaranth isn’t enough to keep it from spreading. Farmers with land near the initial outbreak site in Preble County organized a public meeting to inform other neighbors and plan a coordinated response. “There was a community attitude of wanting to eradicate it,” Smith says.

During the informational meeting, participants passed around a sign-up sheet to collect names of people willing to help with control efforts. Then the Preble SWCD became involved to urge farmers to check their fields and organize groups to walk infested fields to hand pull the weeds. Ordinarily, the SWCD doesn’t fill that type of organizational role, but since the county doesn’t have an agricultural extension educator, SWCD staff stepped in to help coordinate the identification and control efforts, Smith says. “We and most of the farmers were taking a now-or-never attitude as far as trying to get rid of it before the plants in the fields were able to produce their own seeds,” she says. The SWCD also mailed out a factsheet with information on identifying the weed and controlling it.

Gene Tapalman, who farms one of the fields where Palmer amaranth emerged, says he had heard of the problems with Palmer Amaranth in other states, but figured he’d be retired before he’d have to worry about it. “Now here I am, about the first one in the county to get it.” His family has been farming in the area since 1889 and they’ve always tried to improve the land. He’s 66 now, and starting to scale back his operation. His goal is to have the Palmer amaranth eradicated by the time he quits farming.

LOOKS LIKE TROUBLE: Just one Palmer amaranth plant has the potential to produce hundreds of thousands of seed. To prevent worse infestation in future years, every single plant must be destroyed.

LOOKS LIKE TROUBLE: Just one Palmer amaranth plant has the potential to produce hundreds of thousands of seed. To prevent worse infestation in future years, every single plant must be destroyed.

The infestation on Tapalman’s farm was limited to a single 18-acre soybean field, and the infestation was relatively light — about 20 to 30 plants in all. Even so, he spent about 100 hours walking the field to pull the weeds with help from his wife and another area farmer. Along with the Palmer amaranth, they found water hemp, a close relative of Palmer, that had escaped his herbicide, so they pulled those weeds as well. The field was walked twice, then Tapalman watched closely from the combine and stopped several times to pull suspicious weeds. To contain and destroy the seeds, he bagged the weeds and burned them.

Tapalman combined the infested soybean field last and then used a leaf blower to clean the combine before leaving the field. Back at the machinery shed he cleaned it again. “I never used so much air on a combine,” he says. He made note of the first field he went to when he started combining corn, so he can watch that area closely this year along with the original infested field. Although rotating to corn in the infested field would give him more herbicide choices, he’s planning to plant soybeans again because the weeds can be harder to see in corn. “If it’s there, I want to see it,” he says.

Besides walking his own fields, Tapalman joined a group of about 20 to walk an infested field for another farmer. The initial outbreak was on ground where manure from a local dairy had been applied, and the suspected source of the weed seed is hay brought to the dairy from Kansas, where the weed is more widespread. Identifying the source can help other farmers avoid bringing in more of the seed, Tapalman says, but he’s more interested in solving the problem than placing blame. “There’s no use to point fingers, you need to get out and pull it,” he says.

Avoiding problems

In some areas of the state, the presence of Palmer amaranth has resulted in conflicts between neighboring farmers. Landowners concerned about uncontrolled infestations on adjacent land have asked township trustees to enforce the state’s noxious weed law to clear out the weeds before they spread. Other landowners are considering lawsuits over the damage to their farmland productivity and property values caused by the introduction of the weed. To head off such legal conflicts, as well as additional herbicide expenses and yield threats, farmers need to be proactive about controlling Palmer amaranth, especially if their fields have been exposed to possible seed sources.

After the buzz of publicity surrounding the first identified infestation in Preble County, farmers throughout the county began taking a closer look. Two additional infestations were identified, Smith says. One infestation was found in a field where manure from that farm had been applied, so the seed may have come to the farm in animal feed. The other case was traced to rice hulls that had been mixed with seed for a pollinator habitat plot. “If we found three separate sources in this county last year, it’s probably going to be popping up everywhere,” Smith warns. Besides traveling into Ohio from other states in livestock feeds, Palmer amaranth can be carried in on used equipment, or introduced in cover crop or wildlife seeds grown in infested areas.

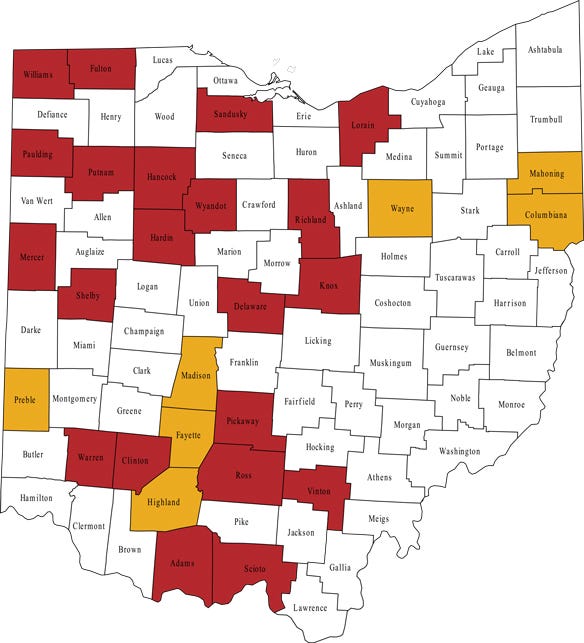

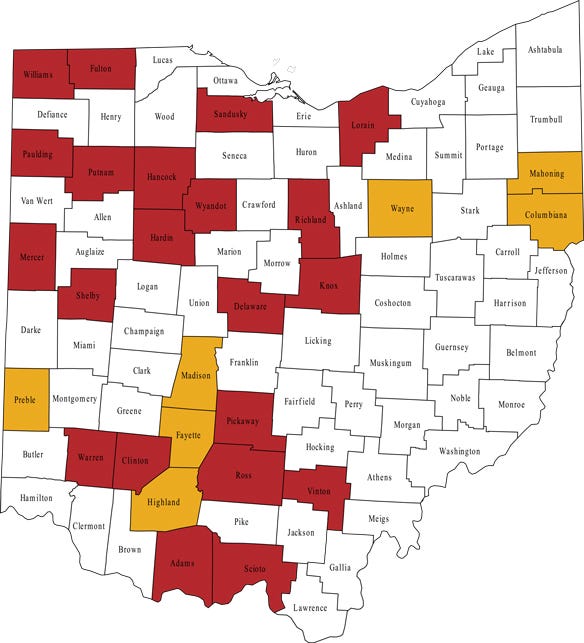

HOT SPOTS: Palmer amaranth has been found growing in each of the highlighted counties, however some of those infestations consisted of only a few plants that have been destroyed. Those counties highlighted in yellow have the most widespread infestations.

HOT SPOTS: Palmer amaranth has been found growing in each of the highlighted counties, however some of those infestations consisted of only a few plants that have been destroyed. Those counties highlighted in yellow have the most widespread infestations.

Neighborly cooperation can help prevent the spread of the weed, Tapalman says. Farmers can look out for one another and alert each other if they find the weed on their own land or on someone else’s. For instance, last summer Tapalman took a few minutes to check a suspicious weed he saw at the edge of a neighbor’s field. It turned out to be a deformed marestail with herbicide damage, but initially he thought the arching stem might be Palmer amaranth. “We all have to work together on this,” he says. “One weak link in the chain can set us back five years in this battle.”

Online resources

For videos and factsheets on Palmer amaranth identification and control, go to the Ohio State University Weed Management website.

Select the Palmer amaranth tab on the weeds pulldown menu.

Preble County’s Palmer amaranth resources are available online as well.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like