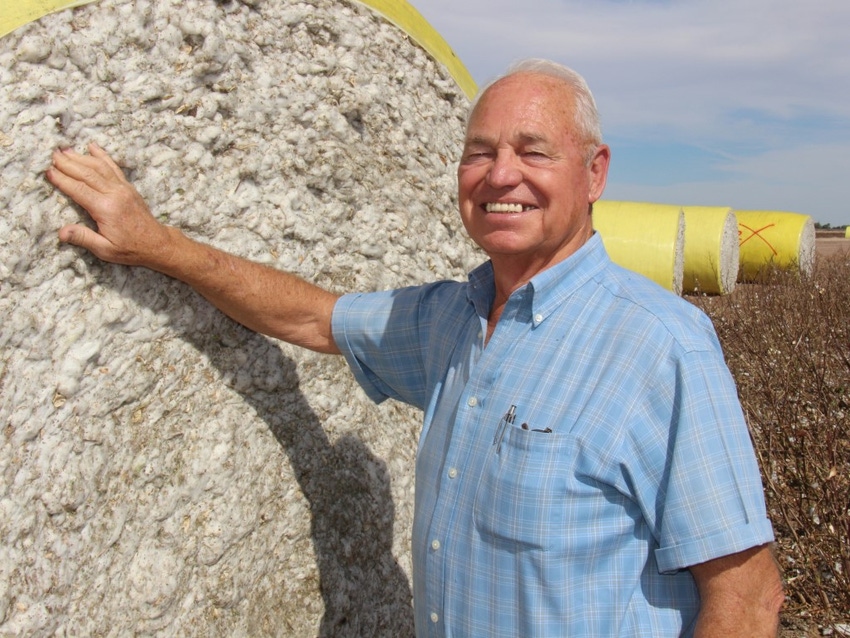

High Cotton winner dedicated to family, agriculture

Clyde Sharp, Roll, Ariz., is the winner of the 2014 Western Farm Press High Cotton Award.Sharp is a highly successful cotton grower, environmental steward, and national cotton industry leader.The Sharp family grows Upland cotton, alfalfa, wheat, onions, and Sudangrass in the Arizona low desert.

January 6, 2014

Clyde Sharp celebrated his 70th birthday last September — but it wasn’t a traditional birthday with cake and candles, sitting around a table with his family on their farm in Roll, Ariz.

Rather, he sat at a conference table in Jakarta, Indonesia, with a group of U.S. cotton leaders, discussing with Asian manufacturers the attributes of high quality American-grown fiber.

Sacrificing a milestone birthday celebration is just another example of Sharp’s exemplary dedication, sacrifice, and leadership on behalf of the U.S. cotton industry.

For that service to cotton and agriculture as a whole — plus the fact he’s a top-notch cotton grower and steward of the land — Clyde Sharp has been named the Far West Farm Press/Cotton Foundation High Cotton award winner for 2014.

“I am very thankful for this recognition,” Sharps says, pointing out the award is really a recognition for his family.

Clyde and his brother David, third-generation Arizona farmers, own and operate Lyreedale Farms with their wives, Vicky and Melissa, respectively. Clyde and Vicky have three daughters — Kayla, Holly, and Kelly.

Clyde, who has farmed for 50 years, was nominated for the High Cotton award by Arizona Cotton Growers Association Executive Director Rick Lavis.

“Clyde is not afraid of a challenge, and works hard to achieve the desired end result,” Lavis says. “He approaches a problem with zeal. His is a rare kind of leadership.”

The Sharp's farm is in the arid Arizona low desert, about 250 feet above sea level about 20 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border. Annual rainfall totals a mere 2.5 inches. A combination of surface water irrigation and the desert heat create excellent conditions for growing quality cotton with good yields.

“This is an absolutely great area for farming and growing,” says Sharp, whose family has grown Upland cotton for 25 years.

In 2013, they farmed 2,500 acres of cotton (fiber and seed), alfalfa, and wheat, plus Sudangrass and onions for seed in Yuma County. Cotton is a rotation crop with winter vegetables.

This area is the nation’s winter produce epicenter — its winter vegetable capital. About 80 percent of the vegetables consumed in the U.S. during the winter months come from Yuma County and neighboring Imperial County, Calif., to the west.

The demand for produce acreage fluctuates from year to year, tied to market demand. This determines whether the Sharps will grow early- or mid-season cotton. Last year, the demand for winter produce ground was so strong they grew short-season cotton, which meant sacrificing the top crop.

Four-bale, short-season cotton

They planted NexGen 1511B2RF in mid-April; the crop was harvested in early October and was ginned at Growers Mohawk Gin at Roll and marketed through the Calcot Limited cooperative. Sharp is vice-chairman of both organizations.

Despite the short growing season, Sharp’s cotton yield was 4 bales per acre. Their round-module pickers harvested an average 3.66 bales per acre and Rood machines collected another one-third bale from the bottom of plants and lint on the ground.

Sharp grins from ear-to-ear in talking about his record yield, and admits to a bit of luck. The local gin average was less than 3 bales per acre.

“I’ll take luck over skill any day,” he says. “I like to experiment with new varieties.”

He credits lower humidity during the summer monsoon season, cooler summer nighttime temperatures, the NexGen variety, and farming skill for his bale-buster crop.

For generations, farming has been a deep passion for the Sharp family. Clyde and David’s parents — Lynn and Irene Sharp — operated a dairy in the greater Phoenix area and grew crops for the cows. After graduation from the University of Arizona, Clyde helped run the dairy, while David managed the crops.

With ever-increasing urban encroachment in the Phoenix area, the Sharps sold the dairy operation and moved to Roll in 1987, shifting totally to crop production. It didn’t take long for them to put down roots and make their mark at local, state, national, and international levels.

Among the life lessons their parents instilled in the Sharp boys was the importance of community service and giving back to the agricultural industry.

For example, on the community level Clyde and David built a country-size barbeque grill with a flaming blowtorch and sheets of metal. Over the years, they have cooked barbeque for various worthwhile causes, with proceeds supporting 4-H, FFA, Rotary, and other organizations. The brothers claim title to the best barbequed meats in the West.

When the local gin manager stopped by seeking a candidate to represent the area on the Calcot board, it opened doors to numerous future leadership roles for Clyde. Today, he is a National Cotton Council executive committee member; chairman of the NCC’s cotton grower arm, the American Cotton Producers; a member of the NCC Boll Weevil and Pink Bollworm Action Committees; ACGA board member; member of the local Natural Resources Conservation District Board; and an elder at the Mohawk Valley Community Church.

Previously-held positions include three years as ACGA president, several years as chairman of the Arizona Cotton Research and Promotion Council, chairman of Cotton Council International, and Cotton International board member.

Environmental stewards

In addition to service to the agricultural industry, the Sharp brothers embrace environmental stewardship practices on the farm. They were the first growers in the Wellton-Mohawk Valley to plant Bt cotton, thus reducing insecticide and herbicide usage. They viewed Bt as the potential future of cotton — and they were right.

They use 100 percent GPS guidance systems on their farm equipment, reducing fuel use and dust by making fewer passes over the fields. The switch from laser-based land leveling to GPS leveling has also improved efficiency.

Fields are developed into blocks, based on soil type, to help conserve water.

“We apply the minimum amount of water on a field and have no tailwater,” Sharp says.

Water for irrigation is canal-delivered surface water from the Colorado River, with an average cost of about $22 per acre foot. Their cotton is grown with about 4 acre feet of water. Cotton rows are 42-inches wide to match the width of lettuce beds.

The Sharps are experimenting with adding commercial bacteria to the soil, with the goal of using the microorganisms to improve bacterial balance.

“The theory is that we’ll use less fertilizer and less water,” Sharp says. “We haven’t used the bacteria long enough to determine if that is the case. But, it has improved stand longevity and the soil profile, which reduces the tractor horsepower needed to till the soil, in turn saving fuel.”

Their main cotton pests are lygus, whitefly, spider mite, and occasional stink bug outbreaks, which usually require one or two insecticidal sprays per season.

Pink bollworm battle

Notably absent from the insect list is the destructive pink bollworm, once the top pest threat for Arizona cotton growers. And this is where this story gets more interesting.

Sharp and others have championed efforts to eradicate the ‘pinkie’ in the West and Southwest.

In 1998, an Arizona referendum to launch PBW eradication was defeated by growers.

By the mid-2000s, Arizona cotton leaders reorganized and launched a second campaign to put the pinkie in the eradication crosshairs. Sharp, Rick Lavis, the ACRPC (the statutory authority to carry out the eradication program) led by Larry Antilla, and others lobbied hard to pass the second referendum.

The guts of the program would include Bt cotton, sterile insect technology against native pinkies, pheromone rope, and traps. Also critical to passage was for Mexico to fully participate in the program, including the related costs.

“We guaranteed Arizona cotton growers we would not conduct the eradication program unless Mexico agreed to fully participate, which they did,” Sharp says.

Growers were asked to grow Bt cotton, with the ACRPC taking care of spraying and suppressing the insect thorough grower-authorized funding.

In 2004, Arizona cotton growers passed the referendum by a 77-percent yes vote — more than the two-thirds required for passage. Moving forward, growers planted 98-percent Bt cotton.

From 2007-2009, Sharp served as the ACRPC chair. He and Antilla launched the eradication program in one cotton region at a time. The guarantee to growers was to complete the assessment phase of the program in four years in each region.

Accomplishing the goal was far from easy. Several growers attended eradication meetings and voiced opposition. But, says Sharp, “Those same growers have come to me over the last several years, congratulated me, and thanked me for pushing eradication.”

“Clyde was one who wouldn’t take no for an answer,” says Antilla, now retired. “His aggressive, but positive, leadership skills and tenacity helped move the eradication program forward.”

Today, PBW program operations continue by the council under the leadership of the ACRPC’s new director, Leighton Liesner. The last native pinkie found in Arizona was in May 2012.

The eradication effort was successful due to the tireless dedication of many cotton leaders, including Sharp.

“As the ACGA president, I championed eradication of the pink bollworm,” he says. “I made that known to growers when I took office, and I worked hard to accomplish that goal.”

Today, California, Arizona, New Mexico, west Texas, and northern Mexico are very close to official PBW eradication. Three to four years must pass from the last native pinkie find before official state eradication status can be declared.

“This makes me feel great,” Sharp says. “It’s a huge sense of accomplishment.’

Cotton leader

Switching gears to federal farm policy, he has played a vital role in helping the National Cotton Council draft and garner support for a new cotton provision in the law. He has helped the industry navigate through important farm bill issues under an abbreviated time frame, says Craig Brown, NCC vice president of producer affairs.

“Clyde has demonstrated great leadership during this important process, and has been a good consensus builder at a very important time — he has done a great job,” Brown says.

Farm Press congratulates Clyde and his family on their High Cotton award.

You May Also Like