August 13, 2018

Source: University of Illinois

Those of you who follow me on twitter (@ILplantdoc) likely noticed numerous photos that I posted earlier in the season of Physoderma brown spot and node rot (PBS) on corn. Over the last week, I have had several calls about this disease, and reports indicate it was more prevalent than usual, not only in Illinois, but also surrounding states including Iowa, Indiana, and Minnesota. Many of the questions involved how the fungus works and potential yield impact.

Physoderma brown spot is caused by Physoderma maydis, a soil borne chytrid fungus. P. maydis produces resting spores called sporangia, which allow the pathogen to persist in soils for up to 7 years in the absence of corn. When temperatures are warm (75-85°F) and sporangia are saturated in water for at least 72 hours, they germinate and release copious amounts of motile zoospores. Zoospores infect meristematic tissues (growing points of the plant). Consequently, infection is generally limited to the leaf whorl, and disease severity is likely to be most pronounced when persistent, heavy rains occur in the spring while plants are still in the vegetative stages of growth. Once infection occurs, zoospores develop infectious hyphae, which enter plant cells and eventually produce structures that contain new sporangia. These sporangia are returned to the soil in corn residue.

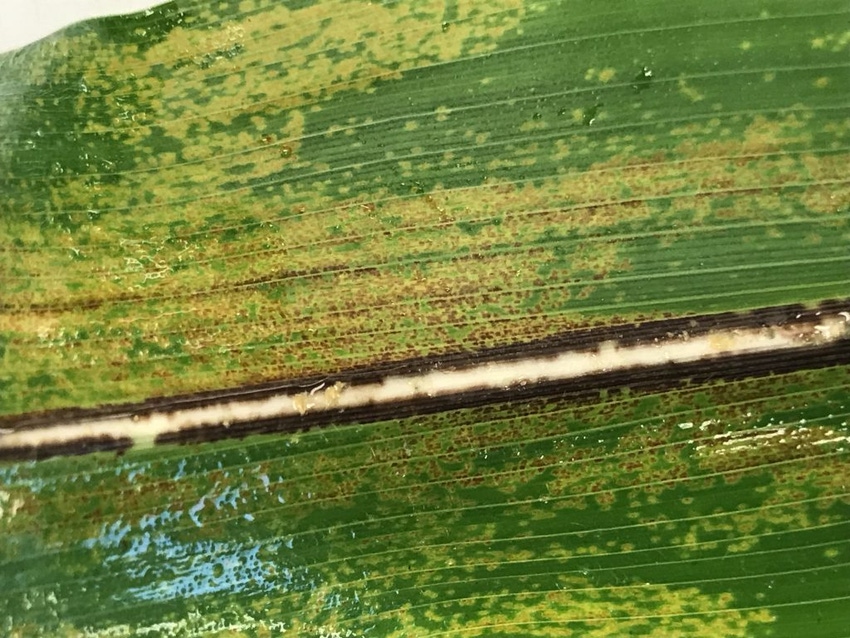

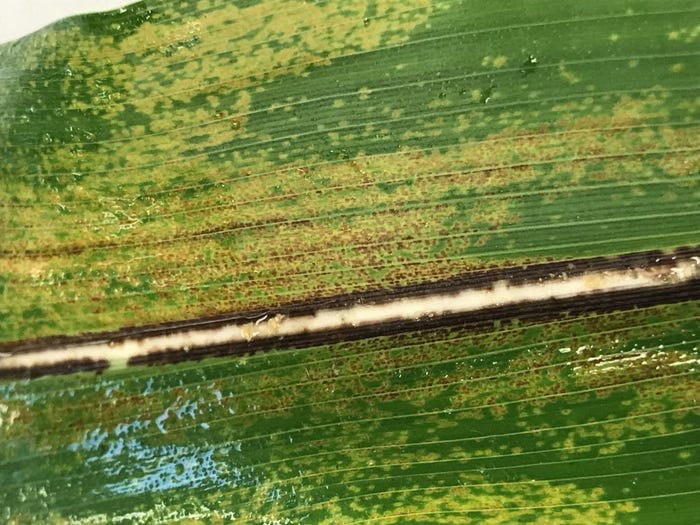

Symptoms of PBS include small, round, yellow to light brown flecks on the leaf blade, leaf sheath stalk, and ear husk. Over time, these specks turn red to brown, and often have a shiny appearance. Spots are distinctively round in many cases, and may coalesce into larger blotches. Foliar infections often are observed in bands, as zoospores require light to infect tissues. Symptoms can easily be confused with purple leaf sheath, a non-destructive condition caused by saprophytic fungi feeding on pollen after tasseling. Infection of the node can result in a brown to black decay, increasing the potential for stalk breakage. Often infected plants grow well without any noticeable impact on ear or kernel size. Generally, losses are related to lodging. For example, in the early 1970’s, Physoderma outbreaks in Illinois resulted in up to 80% lodging in some fields. Foliar symptoms and node rot may not occur together, and there is anecdotal evidence that some hybrids are more susceptible to one form of the disease over the other.

The increase of PBS over the last 5-10 years is likely due to a combination of crop genetics, production practices, and wet spring weather. Data from Iowa indicate that reports of PBS are more severe when excessive rains occur. In 2014, PSR was reported from parts of Iowa receiving 3.9-5.2” of rain on a one week period when corn was between V5 and V9. This season parts of Illinois received abundant, persistent rains during the early, vegetative phases of growth. Consequently it is not surprising to receive more reports of this disease in 2018.

As far as management is concerned, we still have much to learn. However, it is important to note that although some fungicides are labeled for PSR, recent research from the region has not shown these to have any efficacy on this disease or yield. The most important thing with PSR is node rot. Consequently, this disease should be treated as any other stalk rot pathogen. Fields should be scouted between R3 and R5, and tested for standability using a standard method such as the push test. Fields with greater than 10-15% lodging should be on the front-line for harvest, to reduce potential lodging issues.

Originally posted by the University of Illinois.

You May Also Like