The semiarid High Plains areas of the Great Plains and Mountain States are quite different than other parts of the country. Crops are different. Topography and elevation are different. The methods used by landowners to plant trees differ as well, mostly because of unique soil types and far less precipitation.

At a Nebraska Forest Service windbreak short course, NFS northwest district forester Doak Nickerson of Chadron, Neb., discussed site preparation for tree plantings on the High Plains.

Nickerson is quick to point out that soil moisture is everything when it comes to planting trees under conditions of less than 14 inches of precipitation annually. With drier and windier conditions on the High Plains, numerous strategies are necessary to conserve moisture for tree plantings — and to protect the soil from excessive drying and wind erosion.

Save moisture

“Plantings will suffer from poor soil preparation,” Nickerson says, “especially when it is coupled with inadequate weed and grass control.” He suggests controlling grasses, crops and weeds with herbicides a year in advance in a 6- to 8-foot swath where trees will be planted.

“Fallow for this region is not just protecting the ground from vegetation in the fall; it is protecting it for an entire year ahead of time,” Nickerson explains. On crop ground, killing the crop and keeping the dead crop residue weed-free is part of the fallow process. The same method could be used on grassland.

Nickerson recommends leaving vegetation between the 6- to 8-foot swaths, because standing dead vegetation will catch snowfall in the winter and add moisture to the soil before planting.

Other methods of site preparation include wide scalping, which uses a motor grader to remove 3 inches of soil in a swath 6 to 8 feet wide from the upwind side, followed by deep tillage or a roughening of the soil one year in advance of planting.

The windrow of soil left from the process catches winter snow. Then, before planting in the spring, the soil windrow and dead sod is spread back out over the swath where the trees are to be planted.

Narrow scalping of a furrow that is 12 inches wide and 3 inches deep — which is another method used on the High Plains — is accomplished with two small plow share attachments or scalpers that mount on both sides of a tree planting machine’s coulter wheel. The units scalp the soil and dead sod residue as the tree seedlings are being planted.

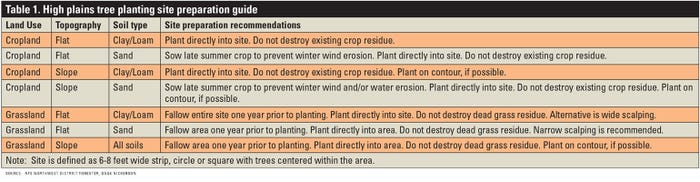

On cropland sites that are being planted to trees, Nickerson recommends deep-ripping the site one year in advance to remove any hardpan that would have developed after a century of plowing or disking the ground. This might be especially important on heavily tilled sugarbeet fields. See the table above for specific recommendations for site preparation under different soils and land uses.

Firsthand experience

Nickerson says that he has seen the benefits of site preparation firsthand. He photographed two Rocky Mountain juniper trees that had been planted in Sioux County in the same field on the same day.

One tree was planted into shortgrass prairie without site preparation of any kind. The other tree was planted into ground that had been prepared. Ten years later, the juniper planted on the unprepared site was 2 feet tall, while the other tree planted with site preparation was 6 feet tall.

After planting, fabric weed barriers or herbicide control of weeds and encroaching grass within the planted strips is also crucial in tree survival, specifically in these arid regions, Nickerson adds.

Learn more by contacting Nickerson at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like