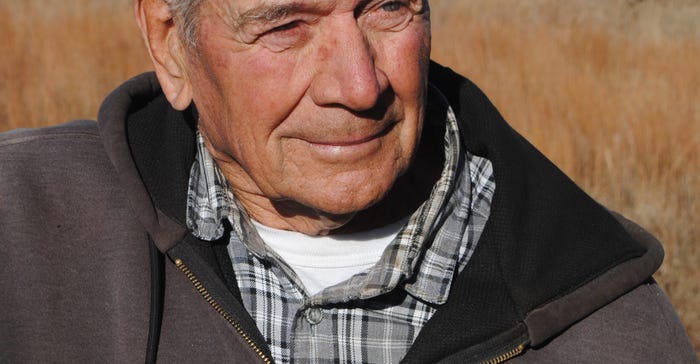

Wayne Rasmussen understands how eastern red cedar tree encroachment can sneak up on landowners. “When the cedars are small, or there are just a few, it doesn’t seem like much of a problem,” Rasmussen said.

After experimenting with mechanical tools to defeat the encroachment on 1,280 acres of grazing land in Knox County north of Winnetoon, Neb., Rasmussen began using prescribed fire in 2015. In a Nebraska Grazing Lands Coalition presentation held recently, Rasmussen told participants, “I could cut 2,000 trees a day and couldn’t get ahead. It takes an immense amount of labor to cut trees, and it is frustrating to see the trees regrow in two or three years.”

That’s why prescribed fire became Rasmussen’s main weapon. “In 2015, I started to burn the pastures,” he said. “I divided the entire tract into seven divisions, leaving one paddock in rest each year to build fuel for the burn in the spring.”

In this way, he didn’t lose the entire pasture for a year’s worth of grazing. He also cuts some of the largest trees and pushes them into piles a year in advance, to facilitate their burning in the fires.

See the difference

Rasmussen’s grasslands are rolling, with low valleys, high ridges and watering ponds spread throughout. In the fall, when Nebraska Farmer toured Rasmussen’s pastures, we learned the stark differences between paddocks that had been burned and those that had not.

Paddocks burned a year or two ago had only skeletons of smaller-sized trees standing. A few large trees 15 to 20 feet in height may have escaped destruction, but Rasmussen noted that a follow-up burn would kill them.

Paddocks that had been burned were rejuvenated, with multiple species of native grasses and forbs. A small valley where a native black walnut stand had been threatened by cedars was completely free of the invaders. Fire had rushed through the hardwood grove without harming the walnuts and oaks.

Rasmussen said there are numerous benefits. “About 90% of the smaller cedars will be killed,” he said. “It kills small trees that you would not even see if you were cutting mechanically."

“Fire retards the growth of cool-season grasses, and allows the desired warm-season grasses a better chance,” he adds. “It gives me a great opportunity to interseed into the burned area to establish forbs.”

Rasmussen noted his native grasslands now offer habitat conducive to prairie chickens. Deer and cattle prefer open grasslands and new grass growth after fire.

“If you burn in the spring, you can usually graze later in that same year,” he said. “Fire also rids the pasture of old skeleton trees and other dead timber.”

Help from experts

While prescribed fire has been a proven tool, Rasmussen acknowledged there is a general fear of burning. Obstacles such as rough terrain and burning through fences are real. Prescribed burns will require a Nebraska burning permit from the local fire chief, and neighbors should be notified two to four weeks ahead of time as a courtesy.

In Rasmussen’s case, there are professionals and experienced landowners in the area to pitch in. He belongs to the Northeast Nebraska Prescribed Burn Association, a group of 75 producers who join to help each other every year with burns.

There is a small donation for a prescribed burn, and they follow strict guidelines through the process. But the organization provides real, in-person help for each burn. Rasmussen usually provides three or four friends, family members or neighbors as well.

“Liability remains with the landowner,” he explained. “That’s why you must always put safety first, and have a detailed burn plan and a good burn boss.”

The fire boss, which in Rasmussen’s case has been supplied by the local burn association or Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, supervises and coordinates all burning activities. The boss needs to be experienced in fire ignition and suppression techniques on the terrain and the type of fuel load being burned.

Other agencies can provide technical and planning assistance. Rasmussen cited Pheasants Forever, NGPC and local USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service personnel. In 2020, the Nebraska Grazing Lands Coalition started offering help in the form of a fire boss as well.

Agencies often offer equipment such as slide-in water pumpers that fit in the box of a pickup truck, along with fire preventive clothing, radios for communication and drip torches for fire ignition.

“They offer organization and scheduling, and their expertise and experience is very important,” Rasmussen said. “There may also be cost-share funding available through some agencies.”

Good for grasslands and wildlife

Rasmussen isn’t alone in his work. “I think we are starting to see some momentum with prescribed fire in this area,” said Kyle Schumacher, coordinating wildlife biologist with Northern Plains Land Trust in the Verdigris-Bazile Creek drainage region — which includes Knox, Holt, Boyd, Antelope and Pierce counties.

“This past spring alone, even with COVID restrictions, there were more than 15,000 acres of pasture and Conservation Reserve Program land burned in Knox County alone,” Schumacher said. “We are at a point of critical mass with the prescribed burns, with many landowners conducting their first burns safely this past year and seeing the positive results.”

Schumacher said from a rancher’s perspective, if you have an operation that allows for annual burns on a rotating basis through your pastures, as Rasmussen does, you will see the results.

“That system allows you to maintain your pasture, keep your grasslands as grasslands, and keep your cattle eating grass,” Schumacher said. “From a wildlife perspective, our grasslands in this area are a combination of northern prairie, Sandhills grasses and eastern tallgrass prairie. After a fire, it creates a mosaic of different habitats and grassland species.”

We need different habitat structures on the landscape in close proximity to each other, including a large complex of tree-free grasslands, he said.

“Diversity in landscapes and plant species is the foundation of it all,” Schumacher noted. “It provides for more insects, more pollinators, more soil-dwelling species and all the way up the food chain from there.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like