December 20, 2018

How does chemical exposure lead to disease in humans? It’s a question that’s long baffled researchers and medical professionals, but there may soon be an answer and it comes from zebra fish. A researcher at Oregon State University has found a gene in the fish that could lead to a better understanding of how exposure to chemicals leads to disease in humans.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and published recently in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives. The study describes the interaction among potentially toxic chemical compounds, a protein receptor and the newly discovered gene called slincR.

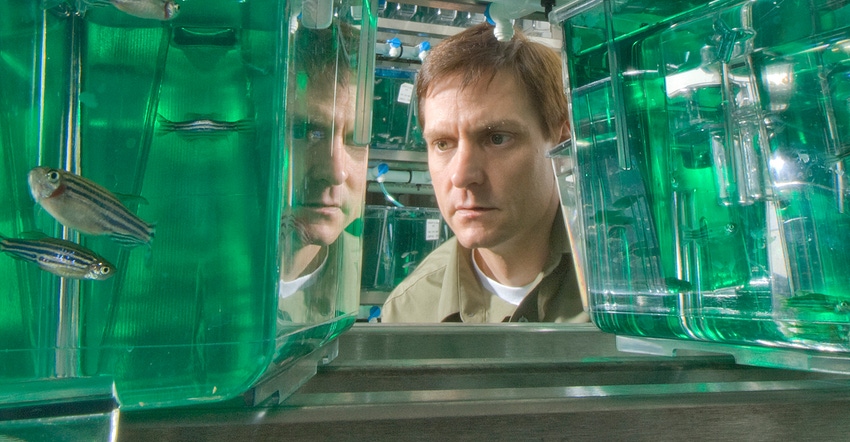

Robert Tanguay, a molecular toxicologist in OSU’s College of Agricultural Sciences and corresponding author of the study, noted that the work “puts a bunch of points on the map” to try to explain human susceptibility to chemicals.

In recent years, researchers have found that zebra fish are a useful model for biomedical research because they reproduce rapidly, and their embryonic genetics and biological systems bear many similarities to those of humans.

Chemicals and exposure

Tanguay explained that a range of chemicals including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) cause adverse health effects in humans and wildlife, and many of those compounds interact with a specific receptor to cause toxicity. “Humans and fish are exposed to these chemicals. In order for a chemical to cause any effect in vertebrates, it must first interact with this receptor. If we understand more about how these chemicals are interacting with this receptor and these genes, we will know more about how they may affect our health,” he said.

In addition to showing that PAHs act as activators for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and slincR gene expression, the study confirmed a relationship between slincR, a non-coding RNA, and sox9b, an important gene for human development.

“This new gene regulates the soxb9 gene, so now there’s a possibility that these environmental contaminants that activate this receptor could be affecting developmental processes in people,” Tanguay said. “We can now predict which of these types of compounds have to react with this receptor, causing downstream events.”

Understanding downstream effects of chemical exposure leads to a better understanding of toxicity-related disease states, and could lead to improved interventional measures to protect susceptible people. “Maybe there are 10 steps between chemical exposure and all the things that have to happen to get a birth defect,” he said. “We can look at those 10 steps in people to see where there are variations in susceptibility. That might explain why some people who get exposed to these compounds don’t get sick, and others do. It’s not magic. It has to be encoded in the genome.”

Source: Oregon State University

You May Also Like