August 27, 2020

If someone suggests perhaps supply controls could help raise U.S. corn prices in the long run, Jim Mintert recommends they look at some facts, figures and charts first. Supply controls basically refer to government payments to farmers to leave ground idle. Set-aside programs were tried in the mid-20th century and as recently as the 1980s.

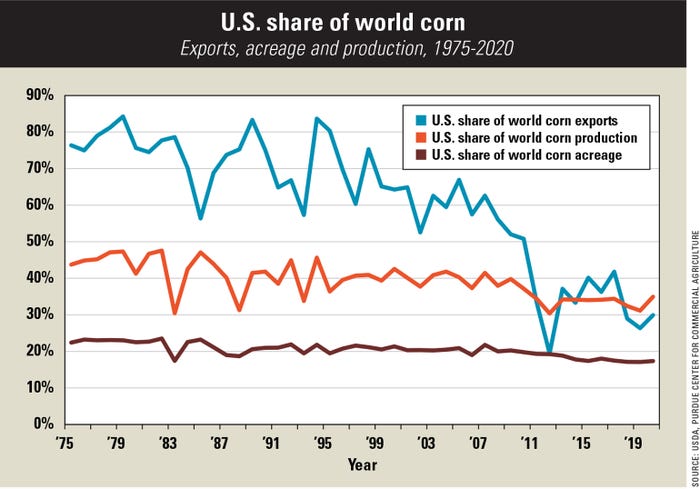

“It was a different world then in many ways,” says Mintert, director of the Purdue University Center for Commercial Agriculture and an Extension agricultural economist. “The U.S. share of world corn acreage has fallen from 22% in the 1970s to about 18% in the 2010s, while its share of world corn production has dropped from an average of 44% in the 1970s to about 34% in the 2010s.”

The biggest change, Mintert says, is in the U.S. share of corn exports. Averaging 70% of all corn exported worldwide in the 1970s, the U.S. share now is much lower, averaging closer to one-third. That’s because other countries grow more corn today than they did in your father’s or grandfather’s day.

What changes mean

The net effect is that if the U.S. attempted to control its production to lower the amount of carryover corn stocks and raise corn prices, companies that buy corn have many other places to acquire that corn compared to 40 or 50 years ago, Mintert says. Instead of helping U.S. farmers, a supply program could hurt, if current customers of U.S. corn find cheaper alternatives elsewhere. Traditionally, once a customer leaves to buy from another source, it’s difficult to get them to return to buy from you.

The bottom line in the long run could be that the U.S. loses market share on the world corn market, Mintert says. Because corn exports are one factor propping up demand and preventing prices from dropping even further, anything that tinkers with exports could have a negative impact on prices.

Livestock factor

At the same time the U.S. share of world corn production has dropped, U.S. exports of meat — led by chicken but also significant for beef and especially pork — have risen dramatically.

“U.S. livestock producers would be less competitive if a domestic supply program actually pushed corn prices higher,” Mintert says.

“Net exports of beef, pork and poultry, which means exports minus imports, have risen significantly over the past three decades,” he explains. “As recently as the 1980s, the U.S. was a net importer of meat. In 2020, net meat exports from the U.S. are expected to equal about 20% of U.S. red meat and poultry production.

“The livestock industry is an important part of the demand side for corn markets. At the same time, the U.S. livestock industry today relies heavily on net exports each year.”

Anything that impacts corn prices could make U.S. meat exports less competitive in the world market, Mintert says.

Comments? Email [email protected].

You May Also Like