The message from Pennsylvania ag leaders is simple. When it comes to highly pathogenic avian influenza in dairy cows, “There is no cause for panic,” said Lisa Graybeal, deputy secretary of agriculture, during a meeting put on Friday by PennAg Industries.

The rapidly evolving situation involving HPAI and dairy cows has led to a lot of speculation and, in some cases, misinformation about what’s happening and how it’s affecting dairy, she said.

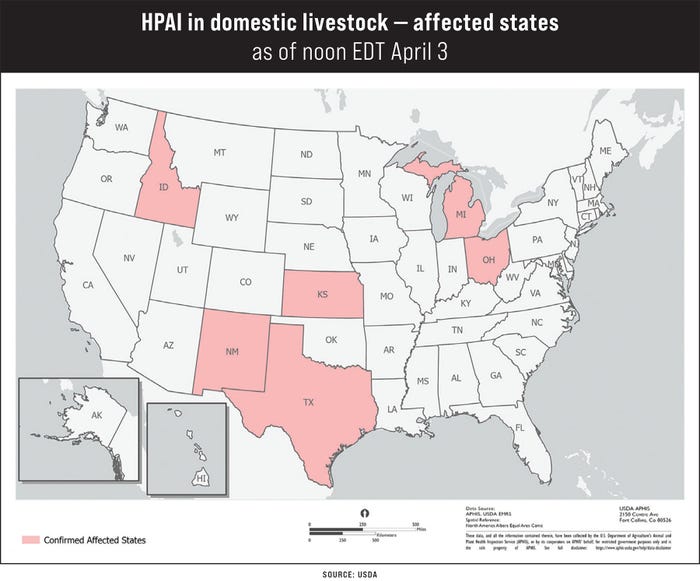

To date, Pennsylvania has not had a positive HPAI case on a dairy farm, although cases have been confirmed in neighboring Ohio and Michigan. See the map below for confirmed cases from USDA:

Alex Hamberg, Pennsylvania state veterinarian, said there was a call for a sick cow on a dairy farm in the state, but after testing, HPAI was ruled out.

He said the state was working on a quarantine order that would require testing of any dairy cows coming in from other states, applying to all dairy breeds and crosses, with the only exception being animals going direct to slaughter.

The quarantine order was officially released late Friday, requiring cattle imported from a state where HPAI was detected to be tested within five days of movement. Testing must be from a representative sample of 30 animals in a shipment, and the animals must have been together for 30 days.

Like USDA, Hamberg stressed that the meat and milk supply are safe, and that pasteurization should kill the virus.

The major risk factor for infection is dairy cows encountering waterfowl and wild birds carrying the disease. Pennsylvania is in the middle of the Atlantic Flyway, a major north-south flyway for migratory birds, which played a major role in the spread of HPAI in poultry in 2022 and 2023.

The state was the hardest hit in the region by HPAI in poultry, with confirmed cases on 32 commercial flocks and 38 backyard flocks affecting 4.7 million birds, according to USDA.

In a story published April 1 by Rachel Schutte of Farm Progress, Dr. Justin Smith, the health commissioner of Kansas, said that the main concern among dairy producers was “nose-to-nose” direct transmission of the virus between cattle. However, that does not appear to be the case. Smith said all testing and reporting showed the virus spreading through unpasteurized milk, likely via equipment in the parlor.

“Assess your farm carefully, figure out the right way forward, and talk to your vet,” Hamberg said.

What to look for

Cornell Pro-Dairy put out an alert stating that dairy cows with HPAI experience drops in feed intake and rumen activity or rumination.

There have been reports of rapid drops in milk production and milk taking on the appearance of colostrum. There have also been reports of abnormal manure — either firm or tacky — and diarrhea, according to the alert. Other less consistent clinical signs are fever and secondary infections.

Peak occurrence in a herd, according to Cornell, is three to four days after the first case, and then decreases in number until it resolves in about 14 days. Virtually all affected cows recover with supportive care after two to three weeks, although some did not return to their previous production level. Affected animals are predominantly older mid- and late-lactation cows.

“This infection appears to be fairly localized to the mammary glands, from what we can tell on the data available,” Hamberg said in the PennAg meeting.

How to protect your farm

Hamberg notes that HPAI in poultry acts much differently than it does in dairy.

The virus spreads quickly in birds, and ventilation fans can eject it from a poultry facility — hence the reason states typically set up control and quarantine areas around poultry farms to control its spread.

Dairy farms are managed differently, and the virus — at least up until now — spreads differently in rumens. If a positive case on a farm were confirmed, Hamberg said it is unlikely that a control area around a dairy farm would be set up, although individual dairy farms would be quarantined.

The Cornell alert recommends the following steps to protect the farm:

Pause or cancel nonessential farm visits.

Assign a biosecurity manager to monitor the situation and develop a farm-specific biosecurity plan.

Notify a vet if cows present symptoms.

Report findings of odd behaviors, or increased numbers of dead wild birds, cats, skunks or raccoons to state health officials.

Avoid importing cattle from affected farms.

Discourage wild birds from entering barns, waterers and feed sources.

Clean and disinfect waterers daily.

Hamberg notes that poultry and dairy farms can be in close proximity, especially in the southeast part of the state. In many cases, farms have poultry and dairy on the same property. Hamberg stressed that farms keep species separated and denote clear boundaries between operations.

New tools available

Chrislyn Wood Nicholson, veterinary medical officer and poultry officer for USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service District 1, said the USDA-APHIS website has been updated with maps and up-to-date information on positive confirmed tests.

The website also includes biosecurity resources from various federal agencies.

Bird Cast, which shows bird migration patterns in real time, provides forecasts of wild bird migration patterns. Pennsylvania and the Northeast are currently in a low-to-medium bird migration pattern, but that is expected to increase over the next few weeks, Nicholson said, with the peak coming in late April and May.

The Center of Dairy Excellence has scheduled weekly conference calls at 1 p.m. Wednesdays to share regular updates. The center is also working with the Penn State Dairy Extension Team to provide “everyday biosecurity kits” to farmers upon request.

These kits include:

A biosecurity “No Trespassing” sign (with both English and Spanish) to display on the farm

laminated copies of biosecurity signage or documents

a visitor sign-in log sheet

a short guide for what to include in your own biosecurity kit

To request a kit, visit centerfordairyexcellence.org or call 717-346-0849. The kits will be mailed out while supplies last.

HPAI dairy timeline

Here is a timeline of recent events involving HPAI:

Early March. The Texas Animal Health Commission receives reports of a health event in Texas Panhandle dairy herds, including reduced feed intake, sudden milk production decreases and milk that is yellow with the appearance of colostrum. Initial cases were isolated to cows in their second lactation or greater, and more than 150 days in milk.

March 19. The Kansas Department of Agriculture receives first reports of similar symptoms in Kansas dairies. Idaho and Delaware issue movement restrictions for cattle from Texas, Kansas and New Mexico dairies.

March 20. A goat kid at a Stevens County, Minn., farm tests positive for HPAI. The goat resided on a farm where a poultry flock had tested positive in February.

March 23. The diagnostic lab at Iowa State University reports a preliminary positive for influenza A in two milk samples from two unrelated southwest Kansas dairies.

March 25. The National Veterinary Service Lab confirms the H5N1 strain of influenza A in samples and starts genomic viral sequencing. The lab finds the Texas and Kansas sequencing is similar and consistent with wild bird introductions.

March 29. A large dairy in Michigan confirms HPAI-positive cows, and Idaho reports a presumed case of HPAI in cattle with a virus strain similar to that from Texas and Kansas. Animal health officials think lactating heifers from Texas herds were moved to Michigan and Idaho herds with the virus incubating in them, but not showing clinical signs.

April 1. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed a person in Texas tested positive for the H5N1 strain of influenza A after exposure to dairy cattle presumed to be infected with HPAI.

April 1. New Mexico reports its first confirmed case of HPAI in dairy cattle, although presumptive positive cases had been reported since March.

April 1. The Nebraska Department of Agriculture issued an order requiring all breeding female dairy cattle entering the state to obtain a permit issued by NDA prior to entry. The order is in place until April 30 and will be reevaluated at that time.

April 2. Cal-Maine, the largest egg producer in the U.S., reported a positive HPAI test at a production facility in the Texas Panhandle that resulted in the depopulation of 1.6 million laying hens and 337,000 pullets. The company also halted production at its Parmer County plant. This marked the biggest bird flu casualty in the U.S. since Dec. 7, 2023.

April 2. Ohio reports its first confirmed case of HPAI in dairy cattle. The dairy received cows on March 8 from a Texas dairy, which later reported a confirmed detection of HPAI.

APHIS is providing regular updates on detections in dairy herds. The CDC is working closely with state and federal agencies and local health authorities to further investigate and closely monitor this situation.

Read more about:

BiosecurityAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like