May 3, 2018

Wheat is a staple food around the world, but as a commodity it is also plagued with market prices that make it unprofitable for many farmers. In western Washington, the grain is an important rotation with potatoes, cut flowers and strawberries; but with such a small amount produced, it’s not profitable. To increase value for their wheat rotation, farmers in the region are starting to think local.

“We try to keep more of the value close to where wheat is produced,” says Stephen Jones, wheat breeder and Bread Lab director at Washington State University in Burlington. “We don’t add value per se, but we don’t let the value be exported, either. We keep the value of what’s created within our agricultural communities.”

He notes that regional use of wheat has created more than 200 living-wage jobs in the last few years, and that most grains grown in the area stay in the region first. Those grains only leave the region if there’s a surplus.

Growers in the region first switched the way they talked about their wheat. Instead of calling it a commodity, they started using the word “food.” They idea wasn’t new; from their other crops, farmers were accustomed to boxing, storing and shipping their own potatoes or daffodils.

“They were already tuned into the importance of keeping more of the value of their crops on their farms, within their community and region,” Jones explains.

Malt and bread are the highest-value uses for wheat. Selling the grain locally created food-chain reactions: There are new malthouses, breweries, flour mills and bakeries. If the wheat doesn’t work for these uses, it is fed to livestock. Many farmers now trend away from corn and soy rations, and include more regional grains for their economical price point.

“We scrubbed away the cliché of local just because it sounds cool,” Jones said. “Local is about the food, its economics and created jobs.”

A variety of flavors

Jones bred commodity wheat for 20 years at WSU before transferring to its Bread Lab. He noticed that wheat grown outside Burlington tastes different from the same wheat from eastern Washington. Instead of developing wheat only on yield, he now monitors terroir — flavor imparted by the environment in which it is produced.

“One wheat has a chocolaty overtone, with a hint of spice,” Jones says. “I’ve worked in wheat since 1977, and we never used those words before, but I now pick up those flavors.”

Each wheat variety holds different flavors. The terroirs are further developed by where the wheat is grown. Burlington farmers now market their wheat by its unique terroir. Jones holds the farmers’ needs first when considering wheat varieties for regional use.

“We want wheat to yield the absolute highest for the farmer,” he explains. “Then we bring it to the lab and find the best function for it, as opposed to just saying, ‘That wheat has to make a Big Mac bun.’ We can have it make anything: a tortilla, pizza dough, rustic baguette or a croissant.”

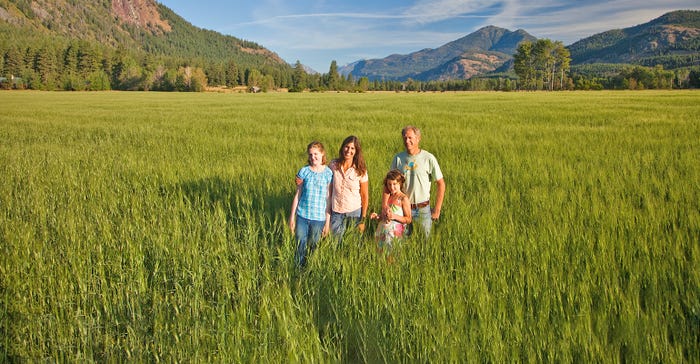

A FAMILY BUSINESS: In Winthrop, Wash., the Lucy family — Larkin (left), Brooke, Mariah and Sam —are increasing their farm profits by growing ancient wheat varieties, operating a custom wheat mill and selling their wheat regionally.

Moving from commodity to specialty markets

The Bread Lab doesn’t test heirloom wheat varieties, like emmer or einkorn, because of their low yields. But these ancient wheat breeds are the mainstay crop for Sam and Brooke Lucy on their organic Bluebird Grain Farms in Winthrop, Wash., 132 miles east of Burlington over the Cascade Mountains. The Lucys started producing emmer in 2003 at the request of a customer.

“We fell in love with everything about it,” Sam says. “Plus, we were looking for year-round income — as opposed to just growing a crop, selling it at harvest, paying all your bills and hopefully having some money left. Now we mill and process our grains year-round.”

“Our emmer and einkorn,” Brooke adds, “are extremely flavorful, and have genetic simplicity and integrity not found in many modern wheats.”

Bluebird’s grains are sold as whole grains, flours and cereals. “We farm up here in the godforsaken wilderness,” Sam jokes, but he is half-serious. “We need to ship a finished product.”

The Lucys are certified organic, and strive for quality over quantity. Sam says the organic grain market is very strong, particularly with consumer concerns about glyphosate residue. But, he cautions, “You can’t just simply throw seed out on your worst ground and then call it organic, because the grain quality won’t be there. You need to be committed to the concept, not just the cash.”

MEETING CUSTOMER NEEDS: For the Lucy family, customizing their product mix allows them to meet diverse customer needs.

Selling it yourself

At Bluebird, the Lucys grow, process, and direct-market their wheats. Brooke explains it as three businesses in one. The Lucys installed their own cleaning and milling equipment because accessible third-party processors either weren’t certified organic or able to handle hulled wheat.

There are several models for marketing wheat regionally: growers have their own mills, like Bluebird; bakeries keep their own mills and purchase wheat raw; regions are served by cooperative mills; growers sell direct to the consumer at farmstands, through CSAs (community supported agriculture) shares or farmers markets; and many farmers do a bit of everything to diversify income.

Another way to serve customers is to custom-mill grain. After harvest, Bluebird stores most of its grain on site at its granary, and the cleaning line draws from wooden granaries. Grain is cleaned and milled each week to customer specification for orders received by the previous Friday.

“It’s as fresh as it gets when it leaves here,” Sam says, “which is a selling point to customers. But custom milling is also a challenge because of the fluctuation. One week we might have a bunch of distribution orders on top of local milling, and the next week it’s just local milling.”

The Bluebird brand has grown, and the Lucys now contract with other local farmers to grow wheat to meet demand. Bluebird products continue to be sold direct-to-consumer through web retail, as well as direct wholesale and through distributors.

While distribution opens new markets, it also brings more paperwork. The Washington State Department of Health and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration inspect the Bluebird mill, on top of the USDA organic certification. Additionally, distributors require third-party audits — for which Bluebird must pay.

“As a small producer, it’s very tricky,” Brooke said of the requirements. “We look at our profit margins weekly, because distributors ask us to pay freight and promotion fees upfront.”

She notes that she sometimes feels bullied by distributors, because they’re used to working with large companies that sell nationally. “I’m sitting here saying, ‘Listen, we grow everything we sell you, and we process it 150 feet from the front door of my home.’ You have to give them that perspective and advocate for yourself,” she says.

Adds Sam: “If you have something the distributor likes, they’re willing to work with you. We’ve hit the point where we know we can sell our wheat elsewhere, and that gives us leverage and confidence to negotiate.”

Customers know best

Selling wheat on the commodity market often disconnects growers from consumers. But people who eat the food have the final word with their pocketbooks.

“Don’t underestimate the consumers’ knowledge,” advises Lucy. “You see the big companies saying, ‘Well, this or that is just a fad. It’s false news.’ Or whatever. But the bottom line is, the consumer ultimately decides the market.”

When selling direct-to-consumer, growers must deliver food exactly as advertised to retain customers. As a producer, Sam knows the pressure: “You get pressed for time, pressed for money. That’s when you need to back up, look at the original idea, and ask, what has made you successful thus far?”

As Jones helps growers produce wheat with unique flavors, he is also careful to not push the price point to where good wheat is an elite food. “We want to make wheat affordable within the regional food system,” he says of the Bread Lab, “and help growers get a little more cash for it.

“Farmers also get satisfaction from seeing their product eaten at local schools, restaurants and bakeries,” he says. “It’s a real sense of pride. Wheat is often grown in such a large scale that you lose track of where it’s going and from which it came.”

Hemken writes from Lander, Wyo.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like