From Walter Raleigh’s first puff of tobacco in the Virginia Colony to King Cotton, the Civil War and all the way to present day, farm exports have been a vital part of U.S. history — and the economic engine of the country. Wheat, corn and soybeans all had their turn in the sun, launching the American Century, and probably a battleship or two as well.

But the U.S. is no longer the world’s dominant bread basket and supplier of choice. Farm exports keep the U.S. trade deficit from ballooning even further, but account for less and less of the country’s economy. Still, the dispute with China that threatened a trade war this spring brought those sales back into the headlines for a nation where less than 1 out of every 1,000 people is a full-time commercial farmer.

Exports are rarely far from front and center for growers, who’ve seen their global market transformed over the last generation. The North American Free Trade Agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Smoot-Hawley Tariff may be obscure names for many Americans. But farmers know firsthand the good and bad of trade policy.

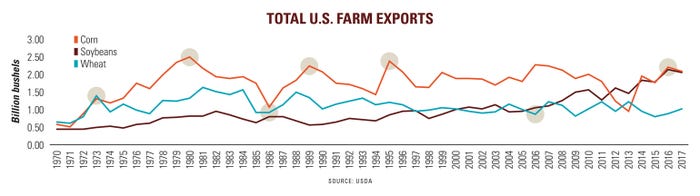

Sometimes exports create vast new markets for U.S. growers, just when they need them the most. But these opportunities are rare: the opening of the global export market in the 1970s in the wake of the Great Russian Grain Robbery, or China’s newly minted middle class triggering an insatiable appetite for soybeans over the past decade.

Most of the time, exports are the swing factor in oversupplied world markets. U.S. sales of corn and wheat only surge when somebody else has a disaster, pushing demand from overseas upon our shores.

Still, a couple hundred million bushels can turn a bad market into a better one, or a better one into a great one. Most of the time, every bushel matters to your bottom line. Those sales are hard to come by because the U.S. isn’t the export powerhouse it once was — and hasn’t been for a generation.

Indeed, cracks appeared long ago in U.S. ag trade. President Jimmy Carter’s short-lived export embargo of 1980 helped make the peanut farmer from Georgia a one-term president and rattled buyers’ confidence. When the U.S. abandoned the wheat market by idling 36 million acres in the Conservation Reserve Program, others stepped in to fill the void.

Buyers didn’t have many alternatives to U.S. corn in the 1980s. But the 1995 drought reminded our biggest customer — at the time, Japan — that diversifying its supply chain was good business. That spurred Brazil’s emergence on the stage. Enough said.

What does the future hold for trade in the wake of the U.S.-China dustup? Here’s a look at how we got here, and what could be next as you look to manage risk.

Things may get worse before they get better

Trade tensions will likely escalate — if we haven’t already seen the high point, says Tom Sleight, president and CEO at the U.S. Grains Council. “Hopefully, everyone will come to the realization we need each other,” he adds. “China needs U.S. food and agricultural supplies. And the U.S. relies on important Chinese goods.

“The hope is that all of the cards are now on the table and that negotiations can come through with a win.”

Time for negotiations

Under the U.S. plan, companies have until May 22 to object to proposed tariffs on imports from China, and the U.S. government then has at least 180 days to decide whether to go ahead, providing ample time for negotiations. Farmers are hoping for a constructive approach to avoid further escalation in the spat between farmers’ top export destination for many of its products.

Wesley Spurlock, National Corn Growers Association chairman, says, “We do have a window of opportunity to reach a mutually beneficial trade position with China until the time that tariffs are fully implemented. We need to be measured, professional and business-like in our approach to keeping the trade doors open with China.”

Animal protein industries require exports

U.S. agriculture is structured to grow through exports. Without exports, contractions would need to occur in production across the board or oversupplies will occur. Domestic protein industries especially have grown reliant on exports. The beef sector has struggled to maintain exports above the 10% production level.

But in 2017, the percent of total beef production (muscle cuts plus variety meat) exported was 13%. For muscle cuts only, it was about 11%. Exports will require continued momentum to sustain current herd expansion plans, says Sterling Liddell, senior analyst for global data analytics with RaboResearch.

Pork exports already in decline

Total U.S. pork exports to China could decline to around 120,000 tons in 2018, down from initial estimates of 300,000 tons carcass weight, according to Rabobank.

Chinese tariffs are not expected to change U.S. hog production materially, leaving alternative markets or increased domestic consumption as the only solutions.

Rabobank expects domestic pork consumption could rise to about 9.9 million tons to compensate for lower exports. If the 25% tariffs on U.S. pork continue through 2019, expansion plans for the industry will likely slow. Corn and soybean production area may face a reduction of 100,000 to 150,000 acres due to decreased pork feed demand.

Little enthusiasm for government assistance for farmers

Shortly after China threatened to place 25% tariffs on U.S. soybean imports, President Donald Trump said U.S. farmers “are great patriots. They understand that they’re doing this for the country. And we’ll make it up to them.”

But there is little enthusiasm among farm groups and Congress toward any government-run mitigation program to help farmers impacted by the self-inflicted wounds of Trump’s trade actions.

“We don’t need another subsidy program,” says Sen. Pat Roberts, R-Kan. “We need trade, not aid.”

Collin Peterson, D-Minn., says he’s against a one-time bailout for a situation created by the administration and considers a buy-off trade policy a mistake.

Brian Kuehl, executive director of Farmers for Free Trade, says, “A mitigation program can’t replace markets that will be lost, and long-term impacts will remain. If farmers must resort to an uncertain, unsustainable government program, while our competitors lock in long-term contracts, the damage will be significant and long-lasting.”

Positive trade outcomes elsewhere could decrease farm anxiety

A modernized NAFTA deal with improvements on agriculture, or at least no damage, could offer some relief to farmers.

“No doubt I’m anxious, but we do expect we can get negotiations done on those,” says USDA Secretary Sonny Perdue on completing ongoing negotiations with Canada and Mexico in NAFTA and on the Korea-U.S. deal.

He says he hopes that can also relieve the anxiety meter to a degree before dealing with the China issue.

Another way to balance the China power is if the U.S. re-enters TPP talks, which Trump dangled in front of ag interests again, before retreating back to a bilateral approach.

Re-examine your balance sheets

Liddell says if there is a 30- to 40-cent drop in soybean prices, it might mean it’s time to reduce debt levels. “It is a good time for producers to make sure they’re capital wise,” he says.

Many operators are now in a position where equipment leases or loans are nearing the end of amortization periods, which lets them restructure some of these decisions.

Make lemonade from lemons

Emotional markets may create opportunities. Anxiety over escalating trade tensions might pressure grain prices. But other markets likely would be swamped, too, because investors and traders react to negative headlines by shooting first and asking questions later.

A plunge on Wall Street could take energy prices lower, when seasonal weakness often is felt in diesel prices as ag demand wanes after planting. Propane also provided some bargains on summer swoons tied to Brexit and the Greek debt crisis.

Fear also could trigger a rush to safe havens, including Treasury securities, and lower interest rates on longer-term loans, just as the Federal Reserve ratchets up short-term borrowing costs.

Corn could again be king

If the tariff on soybeans goes into effect, corn could again return as the most popular crop after losing that title to soybeans this year. But actual changes in prices are difficult to predict because market dynamics are always fluctuating.

Will Trump’s trade gambit pay off?

The trade deficit with China has been quietly ballooning for some time now. Twenty years ago that number was $68.7 billion in China’s favor. Ten years ago, it was $226.9 billion. Last year — $375.2 billion.

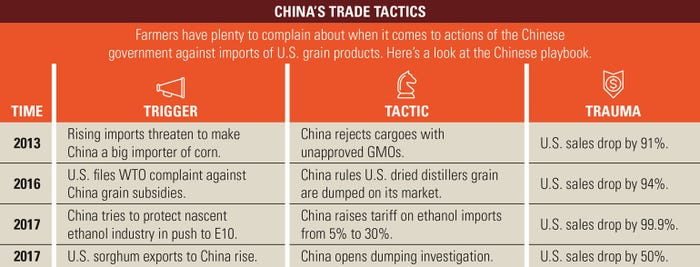

Back-and-forth trade tiffs between the U.S. and China aren’t anything new. China enacted tariffs on U.S. poultry in 2009 in retaliation for a tire tariff. It has also erected trade barriers on U.S. ethanol and dried distillers grain, and those conveniently came after the U.S. challenged China’s domestic support system for its corn, soybean and rice industries.

And earlier this year, China began investigating the placement of tariffs on U.S. sorghum in a move widely seen as a reprisal for the recent tariffs on washing machines and solar panels.

Next, fold in major discrepancies between China and most of the Western world regarding intellectual property. In the U.S., for example, IP is considered belonging to “I/me/mine” and fiercely protected by copyright law. But in China, IP is more of a “we/us/ours” proposition — belonging to the people, to the common good.

That disparity has forced some companies to share their IP with China, an act often seen as the cost of doing business there. And it doesn’t rule out outright IP theft in some instances. Remember the arrests made in Iowa in 2013 after seven Chinese nationals dug up genetically modified corn seeds with plans to send them back to China?

China has also flooded world cotton and corn markets in the past by selling from its state stockpiles.

Enter President Donald Trump. How would a shrewd businessman famous for making deals — yet also known as a hothead who tends to shoot from the hip — fare with the nation’s most important trade partner?

The world’s No. 1 and No. 2 economies need each other. Trump visited Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing in February 2017, and Xi returned the favor with a trip to Mar-a-Lago later in April, with U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilber Ross touting U.S.-China relations “hitting a new high” after the second meeting.

Still, frustrations have mounted within the Trump administration over the continued surge of Chinese imports and ever-growing trade deficits. That led the president in March — against the advice of some of his top advisers — to announce sweeping aluminum and steel tariffs worldwide, making several notable exceptions for trade allies, such as Mexico and Canada.

From there, the trade spat escalated. Later in March, the U.S. announced additional annual tariffs of $50 billion directed toward Chinese goods. China then promised $50 billion in tariffs of its own directed at U.S. products on April 4. One day later, Trump said he would consider doubling down on U.S. tariffs to China to the tune of $100 billion.

As is typical with any trade spat with other countries, U.S. grain and livestock sit at the tip of the spear once more. China’s threatened tariffs include soybeans, corn, pork, wheat, cotton, beef and other key agricultural commodities. This makes logical sense, says Gary Blumenthal, president and CEO of World Perspectives.

“As a competitive net-exporting sector, U.S. agriculture is bearing the brunt of the retaliation,” he says.

Of course, not much happens in trade without leverage. So does Trump have the leverage he needs to bring China to negotiations? Who will blink first?

“China and the EU are saying they’ll negotiate. So yes, Trump will win concessions,” Blumenthal says. “Trump has always played the card that if he has the same or less to lose than his opponent, he wins.”

But even if Trump declares victory, where does that leave the ag industry’s reputation as a reliable world supplier?

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like