April 16, 2018

A lot of people are on the fence about climate change. They think maybe some weather events over the past few years are just within the normal range of variability. Besides, everyone knows weather is cyclical, and maybe this is just a passing cycle. Or maybe it’s all a hoax — fake news.

If that’s your perspective, Dennis Todey, director of the USDA Midwest Climate Hub in Ames, Iowa, has some news for you. And it’s not fake.

“I wish I could tell you that it’s just a cycle, and that it’s going away, but all signs point to other issues,” says Todey, who has a doctorate in meteorology from Iowa State University and is a former South Dakota state meteorologist. “If you look at global temperature data over the past 2,000 years, the temperature changes we’re seeing now are quite unprecedented in recent history.”

Greenhouse gases

Todey has plenty of statistics to back up his claim. While there are multiple causes, he says the biggest culprit is greenhouse gases that are beginning to make subtle and not-so-subtle changes in normal weather patterns.

These changes include: increasing levels of carbon dioxide and water vapor in the air; warming temperatures throughout the world, including the Midwest; more rain in the Midwest’s transitional seasons; warmer summer nights; milder Midwestern winters; more variability in weather, including more rainfalls of 3 to 5 inches or more; low snowfall totals in the mountains of the Western U.S.; winter dormancy breaking way too early; changes in the jet stream; and more.

Todey points out that many changes have both an upside and downside. For example, warming trends have increased the frost-free period in the Midwest by about 10 days in the last half century. This could allow producers to use longer-season varieties.

But warmer weather has also allowed expansion of the Corn Belt into places like North Dakota and Canada, creating more competition.

Todey adds that increased precipitation levels have made it increasingly unlikely that a drought somewhere in the Corn Belt will significantly impact grain prices.

Other negatives present more causes for concern, however. More moisture in the air plus warmer nights can lead to decreased corn yields, increased dew levels and more disease issues. Milder winters allow more insects, weeds and invasive species to overwinter successfully. Hotter weather can cause additional stress on livestock. Increased precipitation levels in spring and fall can lead to more difficulties planting and harvesting, with accompanying side effects, like increased soil compaction.

Todey says some weeds react positively to increased carbon dioxide levels, including Canada thistle and kudzu. “Kudzu loves CO2,” he says.

Seasonality of increased precipitation is a bigger problem than the overall increase, Todey says. Potentially most troubling of all is the flooding and damage changing weather patterns can do to soil.

“Nobody wants more spring precipitation,” he says. “In the spring, soils are particularly vulnerable to erosion and nutrient loss. Heavy rains can even do a real number on frozen soil.”

Take action

While Todey says climate change is here, and you will see more evidence of it in years to come, there are things you can do to mitigate its effects. The most important step is protecting your soil.

“Reducing tillage helps by leaving the soil covered,” he says. “Cover crops also help by providing additional cover and roots to protect the soil and soil structure in the off-season, and by increasing absorption capacity, thus reducing runoff.”

For any farmers who haven’t yet installed pattern drainage, Todey recommends doing so. Tile helps remove excess soil moisture and can facilitate timely planting and harvesting, as well as reduce soil compaction from trying to perform operations on soil that’s too wet.

Finally, Todey says his organization, Midwest Climate Hub, was created by USDA four years ago specifically to help farmers cope with climate change. Located within the Agricultural Research Service in Ames, Iowa, the hub’s goal is to provide information to producers in an eight-state Midwestern area to help them cope with climate change through the innovative links of research, education and Extension partnerships.

Climate change real for this farmer

No one must convince Vincennes, Ind., farmer Ray McCormick that climate change is real. He was talking about it years before USDA climate hubs existed. McCormick, whose operation lies partly in the fertile bottoms of the Wabash and White rivers, has experienced indisputable evidence of climate change firsthand.

“My dad once went 19 years without losing a river bottom crop to flooding,” he says. “Now I’ve had my crops flooded nine of the past 11 years.”

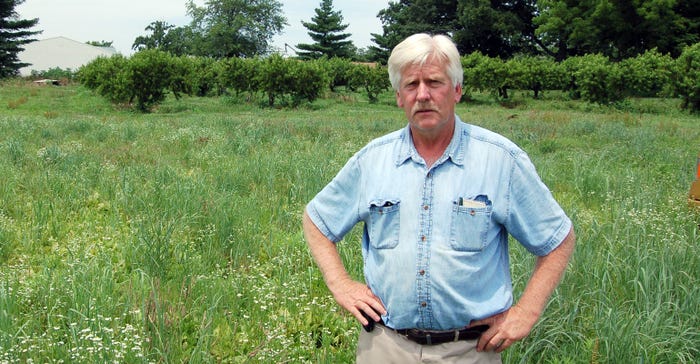

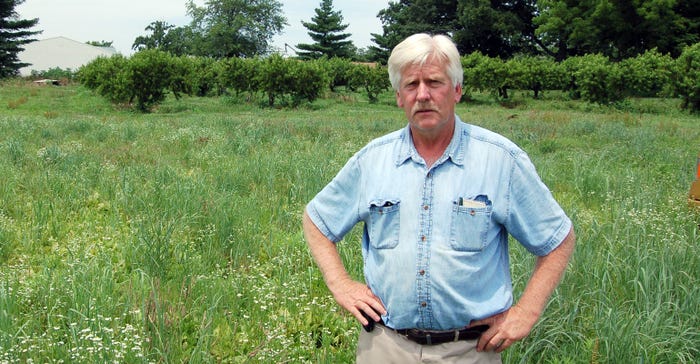

COMBAT CLIMATE CHANGE: Ray McCormick began no-tilling and using cover crops years ago to help improve the ability of his soils to withstand wild swings in rainfall and other weather extremes.

COMBAT CLIMATE CHANGE: Ray McCormick began no-tilling and using cover crops years ago to help improve the ability of his soils to withstand wild swings in rainfall and other weather extremes.

A soil health advocate, McCormick has taken steps for years to not only build soil health and reduce nutrient runoff, but also protect his valuable topsoil from the ravages of flooding. He’s been 100% no-till, which he calls “never-till,” since 1986, and has planted cover crops for about 10 years to build resiliency into his soil and protect it from extreme weather events that are increasing in both frequency and intensity.

McCormick says demonstrations at the National No-Till Conference have shown that each soil health practice that is added provides an extra measure of porosity, which enhances the ability of the soil to withstand extreme weather events. And the longer the practices have been in place, the greater the increases in organic matter and earthworm activity, and the greater the benefit.

“It’s been shown that soil which has been in a no-till-cover crop program for a number of years can absorb more than four times the amount of rainfall, without it running off, as conventionally tilled soil,” he says. “And it can also hold that rainfall in the soil profile for when we need it. We had a 60-plus-day stretch last summer with no rain, and we couldn’t believe the yields we still got. I credit much of that to the ability of our soil to hold that moisture.”

Perhaps one of McCormick’s most convincing arguments for cover crops building resiliency in the soil came about as an experiment he performed, albeit inadvertently. He’s developed a way to sow cover crops effectively using a seeder mounted on the front of his combine. On one occasion in the river bottoms, he forgot to flip the switch to sow cover crops on end rows.

“The next time it flooded, the ground that had cover crops held up very well,” he says. “But where I missed those end rows, I lost 8 inches of topsoil.”

Boone writes from Wabash, Ind.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like