Saltwater intrusion threatens eastern North Carolina crops

• Using a simple, but high tech dam and pumping system, growers can manipulate fresh and saltwater levels in the canals.• The pumping stations and the canals are closely regulated and getting permits quickly enough to avoid saltwater contamination is an ongoing challenge for many growers in the area.

December 27, 2012

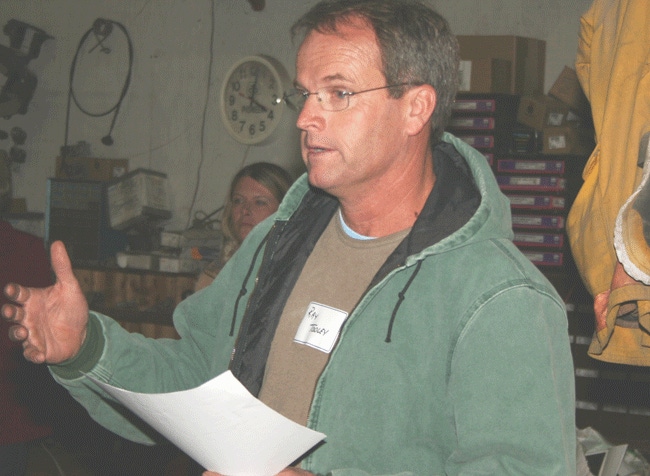

Hyde County, N.C., farmer Ray Tooley grows grain crops and cotton on an eastern North Carolina peninsula that is part of an area of the state called black lands.

Gradual changes in coastal tides are making it more and more difficult for the fourth generation farmer to continue growing crops there.

There is a great deal of debate over the issue of global warming and global tidal change, but Tooley contends there is no doubt in his mind that saltwater intrusion is taking land out of production in his area of eastern North Carolina.

“When saltwater gets on our land you can rub a finger across the soil and a quick lick of your finger will tell you that it’s salty. In some severe cases, you can even see white, salty spots across a field,” Tooley says.

Of course, North Carolina farmers know long before taste and visual tests come into play there is an over-supply of sodium in their soils, thanks to soil testing.

While Hurricane Sandy created some minor tidal flooding in the area, last year’s Hurricane Irene left a large segment of Hyde County under water and destroyed, or at least contaminated, thousands of acres of rich farmland all along the eastern Carolina coastline.

The area in which Tooley farms in North Carolina is called ‘the black lands’. It is aptly named. The thick, rich grayish-black soils are heavy with nutrients and routinely produce three bale per acre cotton and 60 bushel per acre soybeans — both well above average state yields across the Southeast.

Most of the black lands in and around Hyde County, N.C., were re-claimed from marshland back in the 1800s. In fact, Hyde County native and long-time Extension Agriculture Specialist Mac Gibbs says the last water way, or ditch, dug in the county was back in 1950.

The rich black farmland in eastern North Carolina is criss-crossed with a series of canals. Prior to the coming of modern transportation, the canal system was used by everything from pogey boats that hauled produce out of the area to fancy riverboats that brought entertainment to the farming communities, Gibbs says.

Big changes over the years

“I can show you modern day satellite photographs that clearly show the outline of roads and remains of farm houses that are now part of the estuary,” Gibbs says. “There is plenty of historical evidence of thriving farm communities back in the late 1800s and early 1900s that simply don’t exist anymore, due to tidal changes and saltwater intrusion,” he adds.

Now, a canal system is used to pump saltwater out of land re-claimed for farming.

Using a simple, but high tech dam and pumping system, growers can manipulate fresh and saltwater levels in the canals. The pumping stations and the canals are closely regulated and getting permits quickly enough to avoid saltwater contamination is an ongoing challenge for many growers in the area.

“The first thing you have to consider before you plant a crop here is: How can we get rid of any excess water,” Tooley says.

“The rich clay soils on the peninsula go down about five feet, then become sand. Waiting for salt, or in more precise terminology, sodium to filter through the clay and then rapidly filter through the lighter sandy under-soils can be a costly and time consuming process,” he adds.

Cleaning up land from salt water intrusion can take a few years, or in some severe cases up to 15-20 years. Most farmers simply don’t have the resources to speed up the process, nor the time to wait for Mother Nature to clean up the soil from salt contamination.

Adding fresh water is an option, but never an easy one and sometimes virtually impossible. There is no freshwater source near enough to use for irrigation, which would be the simplest approach to reclaiming farmland from saltwater intrusion by flushing out the sodium.

“Most of the water from our nearest freshwater source has 1,200 or so parts per million salt and that’s too high to sustain plant life. Even much lower volumes of contamination would be enough to significantly reduce crop yields,” Tooley says.

One approach the North Carolina farmer uses is a system he calls parallel ditching.

About 12 years ago, North Carolina made available some funding from the National Resource Conservation Service to be used to build flood gates on some of the Hyde County farmland.

Using grant money and some of his own, Tooley and other farmers in the black lands have been able to keep saltwater at bay on much of their land.

Despite their successes, Tooley says the problem of saltwater intrusion is clearly going to continue to be a problem in the region. And, much to his dismay, the problem seems to be getting worse in the past few years.

Since 1996, eastern North Carolina has been hit by seven major hurricanes, the last being Hurricane Irene in 2011.

Speaking to representatives from the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management and the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission — the agency responsible for regulating development in coastal North Carolina, along with state and county leaders in mid-November, Tooley said the equipment shop in which the group was standing, was 3-4 inches underwater during Irene.

Strong water holding capacity

He also pointed out that it doesn’t take a hurricane or 8-10 inches of rain to cause problems in the black lands. “This soil holds water so well that even a half inch of rain at the wrong time can delay planting or drown a recently planted crop,” Tooley adds.

Long-time North Carolina Crop Consultant and member of the Coastal Resources Commission Bill Peele has worked with Tooley for close to 20 years.

He explains the moisture-related problems by pointing out that growers in the region have a very limited window of opportunity to plant wheat.

“A soybean-wheat double-crop works really well for farmers here, but farmers like Ray Tooley have to be right on time, because once this soil gets wet, it stays wet. If they don’t get wheat planted during typical dry spells in October and early November, they usually don’t get it planted at all,” Peele says.

Battling saltwater intrusion is difficult under any set of circumstances, but doing so on primarily rented farmland can be particularly challenging.

Tooley farms about 3,000 acres of land and has 39 landlords from whom he contracts. To make securing land even more challenging, these owners range from Hyde Country, N.C., to Chicago, New York City and several stops in between.

Fortunately, he says, years of trust between he and his brother Charles and the landowners who own the land they farm has created a sense of trust that is critical to making changes.

The downside is that growers, like Tooley, are forced to farm some land they wouldn’t normally work because it’s part of a block of land.

The biggest problem, he says, is that pieces of land will have salt contamination while other pieces of the same landowner’s land will be good. Farming the good along with the bad is difficult and getting worse because of increasing loss of land to salt contamination.

“The ideal scenario would be to put in a large, comprehensive system of ditching and pumping stations, but realistically getting multiple land-owners and conservationists and other special interest groups to agree to such a project, much less finance it, is not likely to happen,” he says.

“An old saying here in Hyde County is that you’re better off messing with a man’s wife than you are messing with his ditches — that’s how important these waterways are to people’s livelihood,” Gibbs says.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like