“Things will get worse before they get better.” That’s the opening warning shot by Damona Doye in her ag land management perspective presentation prepared for the recent OSU Rural Economic Outlook Conference.

Doye, Oklahoma State University Regents Professor and Rainbolt Chair in Agriculture Finance, was unable to deliver her talk at the conference due to a family emergency, but she was kind enough to share her thoughts later with Southwest Farm Press.

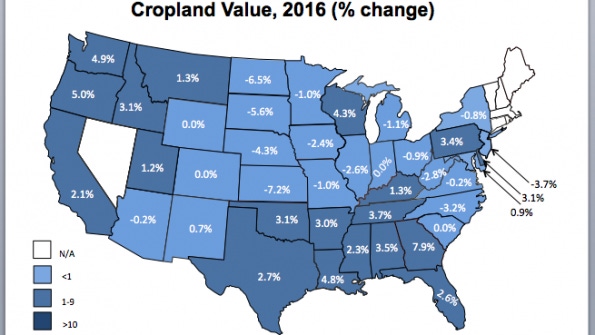

Land values have not fared well across the U.S. compared to a year ago, she says, including significant decreases in some Midwest states. Values in Southern Plains states (Oklahoma and Texas) held up better because rates were not bid up as fast as they were in the Midwest, partly because “the Southern Plains had multiple years of drought, and land values are influenced more by beef prices and income, which until recently were faring better than corn and soybean-focused enterprises.

“Southern Plains land values have held up better, and as of the first of this year, had not yet registered declines. However, more recent evidence shows a softening in land values.”

Even with some stability, Doye says land value increases are relatively small compared to recent years of double-digit increases. Oklahoma cropland value increased by 3.1 percent; Texas is up 2.75 percent; New Mexico increased 0.7 percent; and Louisiana is up 4.8 percent compared to 2015.

A similar trend is apparent in pastureland values, with few states showing an increase. Oklahoma pastureland value improved by 2.8 percent; Texas remained flat; Louisiana was up a slim 0.4 percent; and New Mexico recorded a 2.9 percent increase over 2015.

By late in the year, land values were softening in some of the most productive wheat areas in north central Oklahoma, Doye says. “On average, pastureland prices were increasing at a faster rate than cropland in the most recent year — 5.1 percent compared to 4.7 percent.”

SIZE MATTERS

Smaller parcels of pasture, less than 100 acres, command top dollar, she says. Recently, those smaller parcels have been valued almost $400 more per acre than parcels in the 100 acre to 300 acre size range.

“For pasture, the average per acre value decreases further for even larger parcels. The step down in price for cropland is less dramatic and covers a shorter range of sizes. The largest tracts have a higher value per acre than tracts in the 200 acre to 500 acre range.”

More on Outlook

Doom and gloom pervade Oklahoma outlook conference

Ag downturn exposes vulnerabilities, offers opportunities

Doye says U.S. cropland values show no “dramatic changes when you look at U.S. averages. “We have continued to observe sideways movements in U.S. cropland values. while rates of increase for pasture land values have slowed.”

Less difference exists between Oklahoma’s cropland and pasture land values than is the case for U.S. values, but is comparable to U.S. pastureland values.

Things may be changing. Doye says. Recent findings from the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank survey of ag lenders show dips in both cropland and pastureland values in Oklahoma, compared to 2015.

“Rates of decrease were below the Tenth District average except for irrigated cropland. Kansas cropland values in particular have been relatively hard hit, and for ranchland Nebraska and Kansas had the largest declines.”

A long-term trend over the last 35 years shows Oklahoma cropland values and cash rents increased very little for 20 years following 1991, increased after 2009, but recently came down. “Through January 2016, land values have continued up, though the rate of increase has slowed,” Doye says.

LOCATION MATTERS

Value of cropland varies with location, she notes, and is highest in productive areas such as north central Oklahoma. Areas with significant urban influence also see higher values. Cash rents follow the same trend — higher in the productive north central counties, where crop commodities are very important.

Oklahoma pastureland values have trended upward over the past 35 years, Doye says, although, as with cropland prices through January 2016, land values have continued up, but at a slower pace. “Average cash rents started increasing in the early 2000s, and have continued to increase; they are not yet slowing, as has been the case with cropland rents.”

She says pasture land values are highest in eastern Oklahoma where beef and poultry are the more dominant enterprises. “We see evidence of urban influences around Tulsa and Oklahoma City (as well as Arkansas urban influence in the northeast corner). Pasture cash rents look to be better correlated with the land values in that they are generally highest in the areas with the highest land values.”

For the latest on southwest agriculture, please check out Southwest Farm Press Daily and receive the latest news right to your inbox.

The variability in annual cash rents over time apparently has decreased, she says. Rental rates have outpaced land values across the U.S. “Though both cropland and cash rents went up dramatically in the U.S. in 2009, rents went up relatively more, contributing to the higher rent-to-value ratios.

“Rents relative to values have come down a bit in recent years, but not a lot, and Oklahoma rent- to-value ratios didn’t jump up in 2009. Neither land rents nor land values went up as dramatically as they did in other regions of the U.S. Successive years of drought, along with a different, lower-valued crop mix on average, helped temper exuberance. Pasture land values for both the U.S. and Oklahoma have increased at faster rates than rents since 2004, leading to a now lower, relatively stable rent-to-value ratio.”

Gross returns play a bigger role in farmland values than does net farm income, Doye says. “Ag production values and farm real estate values follow a similar path, while net farm income is at a much lower level, with a widening gap in recent years.”

CROP MIX MATTERS

Oklahoma farmland values have increased, along with agriculture production values. “At the state level, the gap between gross returns and net farm income has widened a bit, but the difference isn’t nearly as dramatic as at the national level. Still, ag production values and farm real estate values follow a more similar path ,with net farm income more variable and trending up more slowly.”

Oklahoma and other Southern Plains states exhibit some unique factors that affect farm revenue and farmland values, Doye says. Important components of farm revenue in Oklahoma include the wheat industry’s current malaise.

“Average wheat yields have not improved significantly since the late 1980s. Weather-related events contribute to significant variability in crop yields, particularly evident in recent years. The state average wheat price has trended up since the 1970s, but again, variability has been a challenge for producers, and recent price declines have contributed to significant pessimism in the industry.”

The beef industry plays a significant role in the Oklahoma agriculture economy and has been a bright spot until recently. “Beef price has trended up,” Doye says, “and contributes to optimism in pasture land markets.” Recent dips in beef prices could temper some of that optimism, however.

How does the value of land affect a would-be farmer or rancher’s ability to start up an operation? How much of a factor is the ability to purchase land with income derived from the farm/ranch? Doye says the trend shows that if a new operator could devote all the revenue from the enterprise to land payments (an impossibility since operators incur numerous production costs), the number of years required to pay for land is increasing.

BANKERS WEIGH IN

Bankers expect farm income to remain weak in the third quarter, she says. “Similar to last year, a significant number of bankers in each district expect farm income in the third quarter to be less than the previous year.

“They expect the rate of decline to be sharpest in the Mountain States and Oklahoma, which are relatively more dependent on income from wheat, cattle, and energy production than other parts of the district. As the outlook in these three sectors has become increasingly downbeat, more bankers in those regions expect farm income to decline further.”

Consequently, bankers are seeing severe repayment problems that are growing, but still at very low levels both in Oklahoma and for the district. “Major repayment problems have increased relatively more, with some growth in minor repayment problems also evident.”

Even producers with higher profitability records face significant risks during downturns. Kansas Farm Management Association data show that differences between the top and lower profitability groups widened during the boom, but have narrowed as profit margins disappeared across the board.

The more profitable livestock producers do have production cost advantages. “Costs of production vary widely among producers, with a nearly $250 difference between low and high profit producers,” Doye says. “The largest determinant in the difference is feed expense. The least profitable group of producers spent more on purchased feed (and less on grazing) than producers with the highest profits.”

Management makes a difference with effective forage management that matches herd size, cow mature weights, and milk production potential to available resources. “Over-grazed pastures result in lower weaning weights and more purchased feed inputs,” she says. “A forage management plan that includes fall-winter grazing and only 60 days to 90 days of fed hay will likely result in higher profits.”

Current crop and livestock prices, production difficulties, and other factors beyond producers’ control may continue to affect land values in coming months. And, as Doye said in her opening salvo, “Things will get worse before they get better.”

Farmers and ranchers who endure the worse will likely do so by relying on efficient management, shrewd marketing, and as always, hard work.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like