Camelina, planted as a winter annual, shows promise as a soybean cover crop and food source for pollinators in field trials conducted by University of Minnesota and USDA scientists.

The oilseed crop also improves water quality by holding back nitrate leaching, which usually happens in the spring in Minnesota.

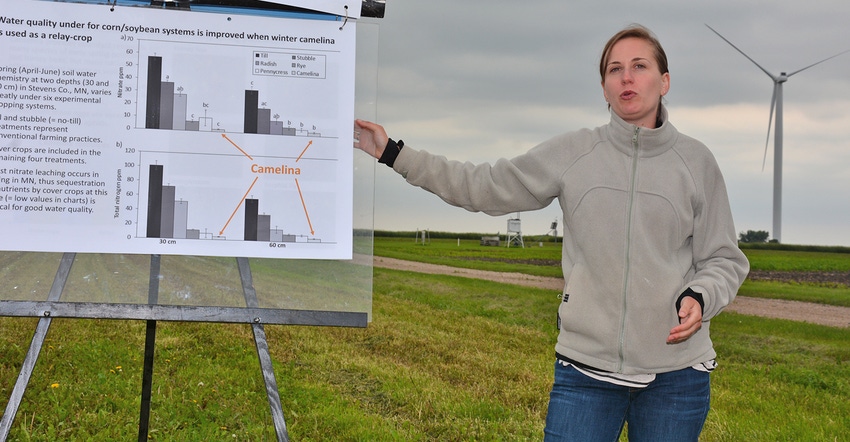

At the U-M Extension and North Dakota State University Extension Soil Health Field Day held in Morris, Minn., this summer, USDA Ag Research Service soil scientist Heather Matthees, agronomist Frank Forcella and plant physiologist Russ Gesch discussed winter camelina plots planted in Stevens County, along with three other cover crops — radish, pennycress and rye.

CASH CROP: USDA plant physiologist Russ Gesch talks about potential markets for camelina, including snack foods, biofuels and bioplastics.

CASH CROP: USDA plant physiologist Russ Gesch talks about potential markets for camelina, including snack foods, biofuels and bioplastics.

The scientists consider camelina a “relay crop,” meaning it overlaps the life cycle of another crop. It works well after small grain cereals such as wheat and edible beans. Camelina is planted from late August through early October. Plants lie dormant in their rosette phase through winter and continue growing in the spring. Camelina flowers from late April through early May, providing nectar for pollinators. Soybeans are then planted between the rows of camelina. By mid- to late June, camelina is ready for harvest using a conventional combine that travels over the tops of small soybean plants.

Yields are up to 1,700 pounds of seed per acre in Minnesota, according to Gesch.

Matthees explained to field day participants the potential for improving water quality when using winter camelina as a relay crop. The scientists looked at soil water chemistry at two depths — 30 centimeters and 60 centimeters — in six cropping systems: till, no-till and plots planted each with camelina, pennycress, radish or rye as a cover crop.

“We found a significant reduction in leaching nitrate and total nitrogen with camelina,” Matthees said. In fact, camelina had the lowest levels of leaching at both depths when compared to the other five plots. Pennycress had the second-lowest level of leaching.

Forcella pointed out the benefits of camelina and pennycress for early spring pollinators.

“We’re in the ‘honey bowl’ of the U.S.,” he said. North Dakota ranks No. 1 in the U.S. for honey, with Montana ranking second and Minnesota usually in the top five.

In June, when bees come back from California, there are not many flowers blooming, so beekeepers have to feed them. Camelina flowers at just the right time for the pollinators. Each year, one beehive requires 100 pounds of nectar sugar and 40 pounds of pollen to produce honey.

The scientists measured camelina nectar production and calculated nectar sugar produced. They found that 1 acre of camelina produces 100 pounds of nectar sugar and 60 pounds of pollen.

“We can easily meet the needs of one hive a year with an acre of camelina,” Forcella said.

He also pointed out another benefit: natural soybean aphid predators.

“Besides honeybees, bumblebees and monarchs, there’s the syrphid fly. It loves camelina and pennycress,” Forcella said. “There are many species of syrphid fly. Females lay their eggs on adjacent crops — for example, soybean leaves — which form into larvae. They are predators — voracious carnivores — and they eat soybean aphids.”

Alongside research that helps pinpoint agronomic practices for a potential crop, efforts must be made to make it commercially viable to raise as a cash crop. Winter camelina seeds contain 42% to 45% oil, Gesch noted, with very high levels of linolenic acid, which is a heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acid, and vitamin E. Matthees said the scientists are working with industry partners such as General Mills and Pepsi on various products, such as snack foods, biobased plastics and biofuels. The seed meal also can be fed to livestock.

“With the relay system, growing corn and soybeans with camelina, you can get more total grain and oil production,” Gesch said. “Relay cropping can add $126 to $144 per acre.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like