Farmers try controlled drainage to keep water, nutrients in place

Think DifferentToo much or too little water accounts for about 67% of the risk in growing corn and soybeans. That risk could be dramatically cut with controlled drainage. On flatter soils, water tables can be raised and lowered with structures inserted into tile lines. The structures double up on tile functions, backing water up in a field when the crop needs it, as well as draining it when there’s too much water. The practice can be applied to both existing tile systems and new tile systems – holding water in the profile during dry times and releasing it in wet springs and before harvest.

May 19, 2015

"I can't make it rain, but I can do my best to capture and keep what I have to use it for my crops," says Arliss Nielsen, a Wright County, Iowa, no-tiller. This year he took the unusual step of venturing into controlled drainage.

At the edge of one flat field this spring, Nielsen installed a water-control structure in a main tile line as well as four water gates to control underground water levels over 13 acres. His goal is to convert drain tile into a water-storage conduit for use in dry times.

"Now these water control structures and water gates do what I've wanted to do for years," Nielsen says.

Nielsen pattern-tiled most of his land five or six years ago. He and his son Todd farm a total of about 1,200 acres in north-central Iowa, renting more than they own.

Nielsen put in his first water-control structure two years ago to manage water entering his underground bioreactor. He installed a second at the bioreactor’s outlet. These structures, installed within tile lines, use stacked panels called logs that are inserted and removed to control the water level backed up in the tile, which in turn raises the underground water level.

"My plan is to have the stop logs in all summer most years and take them out before harvest," Nielsen says. "But if we get heavy rains, I can take the logs out to release the water from the field to the bioreactor farther down-line.”

He checks the water level at the surface inlet at the lowest point in the tile system. This practice was helpful in mid-June, when a 4-inch rain ponded his field. “I took out some of the logs to take care of the surface water, which left quickly,” Nielsen says.

Multiple advantages and incentives

Nielsen planned to add 29 acres controlled with water control structures this fall, which would give him about 100 acres of controlled drainage. “It costs about $500 for a water-control structure and a fair amount less for a water gate. That's cheap compared to the cost of tile,” he says. Two more edge-of-field water control structures are scheduled on Nielsen's land for next spring. Installing them along with new tile is the most cost-effective method, he adds.

While NRCS incentive payments are available for controlled drainage in his county, "I'd be doing it even without incentive payments, if we get the benefits I think we will,” Nielsen says. "I'll have to evaluate this for several years. The 50 acres I'll pattern tile this fall will all include water control structures, and more than a third of the land I own will have water control on it. I've got a son and grandson coming behind me on this farm, and I'd like to have it set up for them.”

Nielsen believes that lowering the cost of the system will also increase the potential for use, along with other incentives such as the advantage against big swings in climate. Keeping nitrogen in the field, which may result in a yield response, is another potential incentive he is investigating.

"Arliss was already doing a good job in keeping nitrates on the farm by using a bioreactor and cover crops," says Bruce Voigts, Boone River Project Coordinator with the Wright County, Iowa, Soil and Water Conservation District. Add controlled drainage and no-till, and Nielsen is giving his land and water the best treatment available, he notes.

Control structures and water gates work together

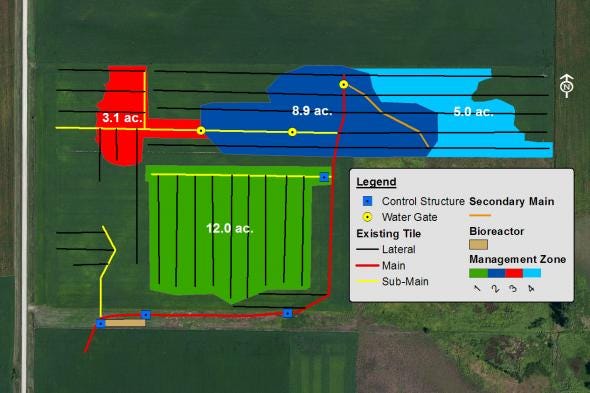

Controlled drainage, which can hold or release water from tile as needed, uses a system of structures inserted into tile mains.

Click for larger image.

The water control structure is a vertical box inserted into a main tile line, usually at the edge of a field. It uses stop logs to block the water coming into it from the tile. As stop logs are lowered into the box, they raise the water level in the field. As they’re removed, water levels in the soil are lowered.

Water gates are placed within tile lines upstream from the water control structures. As water backs into them from a water control structure or another water gate downstream, a float rises and shuts off water flow from the tile upstream, backing up water into the soil profile. Each water gate is designed to raise the water level above it by 1 foot.

Nathan Utt, an engineer with Ecosystem Services Exchange in Adair, Iowa, designs controlled drainage systems. “To be economical, we like to have at least 10 acres controlled by each structure,” he says. Utt says it’s typical to have four or five water gates upstream from one water control structure, but he knows of one system with 25 water gates in a main tile line. “The most economical and efficient systems are designed and placed as part of new tile systems,” he says. In retrofitted situations, a water control structure has to be farmed around, but the water gates are all underground and virtually maintenance free.

Utt notes that fully automated “smart drainage” systems, which use valves rather than stop logs to raise and lower water levels, can save manual trips to the field to adjust logs.

“Instead, a computerized program can automatically regulate water levels throughout the season,” he says. The smart structures, which are powered by solar panels, can also pick up a signal from a cell phone or iPad to open and close valves. Farmers can also set up a remotely monitored weather station along with the structure.

Utt also helps farmers utilize controlled drainage structures to quantify nitrogen loss. “You need to know how much water is leaving the field, and you can calibrate that with a control structure,” he says.

Farmable, farmer friendly practice will grow

Charlie Schafer, president and owner of Agri Drain, the company that manufactures the water control structures and water gates, sees future growth for controlled drainage.

“The NRCS says there are 30 million acres in the Corn Belt that are suitable for drainage water management,” Schafer says. “They’re now proactive on controlled drainage, offering technical assistance and often financial incentives from USDA,” Schafer says. “We’re seeing interest across the Corn Belt, not just in localized areas. Some of that interest is being driven by big weather swings from intense rains to droughts—farmers know there’s value in being able to manage that water.”

Successful farming is about managing risk, Schafer believes. He’s very excited about the capability of farmers who have water sources to install controlled drainage systems that also offer sub-irrigation by pumping water back through tile when it’s needed in the field.

“I’ve seen research from 1948 through 2010 showing that of the things that can impact corn and soybean yields negatively, excess water is responsible for 27% and drought is responsible for 40%. Imagine having a controlled water system that takes away 67% of your yield risk!” Schafer says.

He also foresees a water quality trading program that would allow farmers who can quantify N reductions in water to get monetary credits from businesses or others who need to trade for those credits. “The farmer who can sub-irrigate, reduce nutrient losses, trade credits, and drain soils as needed is set up for the future,” Schafer concludes.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like