Single drug or combination therapy? Many cattle producers face this conundrum when deworming their herds.

For some, the approach boils down to economics, timing and ease of delivery. However, concerns within the industry are mounting over parasite resistance, triggering a need to understand the role each type of dewormer plays in a cattle operation.

Deworming cattle is part of many herd health programs on U.S. farms. Dan Cummings, a veterinarian for Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health based out of Hopkinsville, Ky., travels throughout much of the eastern U.S. from Missouri to West Virginia, advising cattle producers on how to best use deworming protocols. And he finds there is no single approach that works best on all farms.

There is a place for each type of dewormer, along with pasture management, that will keep medications sustainable for the future of the beef industry.

When to use an individual dewormer

Treating an animal with one active drug from one drug class is known by veterinarians as monotherapy, and Cummings says it is still widely accepted and a common practice in the cattle industry.

“It's still highly effective,” he says of single-dose drug protocols, “because we've got an excellent suite of efficacious drugs.” There are a few instances where a single-agent drug or monotherapy works best in a cattle operation:

Mature cows. Cummings says this situation usually comes when cattle are moving off summer pasture in the fall. Cattle producers want to administer one broad-spectrum dewormer or a topical to rid the animal of both the external and internal parasites. “This is still highly effective and beneficial to that cow going into a winter nutrition program,” he adds.

Weaning age calf. In this case, cattle producers can find effective treatment while pushing several young calves through the chute. Here, a single extended release injectable dewormer can be effective.

While age is a factor in a parasite-control program, Cummings says it is important for cattle producers to know just how severe the internal parasite infection is on the farm.

On-farm dewormer trials

Too often, farmers are treating for worms based on sight, particularly as they view hair coat condition and overall animal appearance. Cummings says cattle producers need to realize that there are other causes for long, scraggly-looking hair coats.

“The only way to truly know whether it’s parasites and whether the program’s effective, whether it’s one agent or two, is to have an established baseline for your herd,” he says.

Knowing your herd’s worm load to find the right treatment starts with collecting fecal samples. “This gives us the eggs per gram,” Cummings explains, “and then we have a baseline to make the best parasite-control recommendations."

He is often asked about the economic threshold of worms in a herd, but unfortunately there is too much variation from one herd to the next. “That is why we need a baseline for that individual farm,” Cummings explains.

For example, if the fecal sample shows 100 eggs per gram in that stool sample, that is the starting point. The animal is treated that very day according to the labeled dose. Then the animal is run back through the chute in 14-17 days depending on the product, and the farmer or veterinarian draws another fecal sample.

“I want to see a greater than 90% reduction in that egg count from the first to the second sample,” Cummings says. “So, if it is 100 today, I want it to be 10 or less in two weeks. That is when we know the dewormer program is working. This is called a fecal egg count reduction test, or FECRT.”

He says at the same time farmers or veterinarians collect fecal samples, they should be writing down weights to make sure the animal is receiving the correct dose. Often, cattle producers tend to underestimate weight, which reduces the dewormer’s effectiveness. “We have to be giving the right dose per label according to the weight of the animal,” Cummings adds.

Combination dewormer may be best

All worms in cattle are not the same. There is a common roundworm or “brown stomach worm,” known as Ostertagia. There are the small intestine worms, called Cooperia, and tapeworms, Moniezia benedeni, to name a few.

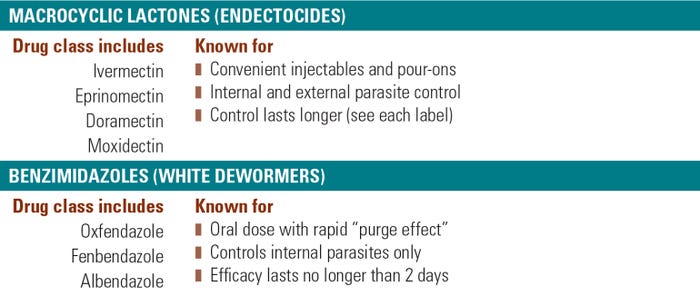

From a U.S. manufacturing standpoint, there are two common drug classes approved for cattle — the “white” dewormers, or oral benzimidazoles, and the macrocyclic lactones, which includes ivermectins.

The white dewormers or benzimidazoles are administered orally, and act as a purge dewormer to internal parasites. These dewormers interfere with the microtubules of the parasites, which depletes the energy supply and eventually causes death of the parasite. Benzimidazole dewormers are usually in and out of the system within a couple of days.

The macrocyclic lactones (endectocides) come in both injectable and pour-on formulations. The active ingredients within these dewormers cause nerve paralysis of internal and external parasites. Macrocyclic lactones provide longer-duration control of parasites compared to benzimidazoles.

It is the combination, Cummings says, that provides effective treatment of worms.

In the 100-eggs-per-gram example, a single drug may kill 90 of them, but there’s still 10 left. “If you add a second drug that is also 90% effective, that response can jump to 99% overall due to the added effect of the dewormers,” he explains. “That’s why combination treatments work. Because those parasites don’t all respond the same across drug classes. And these different drug classes offer different modes of action in a combination treatment versus a single drug.”

While medicine is an effective tool for deworming a cattle herd, it is not the only one, Cummings says. “We’ve been a little bit passive with overall herd management,” he notes, “and the reason is because we’ve had highly effective deworming products that worked great.”

Biosecurity measures

Cummings says cattle producers — feeders, stockers or custom grazers — should consider treating cattle coming onto their farm, then quarantine the group for 14 to 21 days.

He recommends a combination treatment, noting that he has observed “very high efficacy” with it. However, cattle producers need to consider keeping a percentage of the herd selectively not dewormed, known in the industry as “refugia.”

Leaving a portion of the parasite population in “refuge” from dewormers reduces the selection pressure and maintains a susceptible population of parasites. Cattle producers also don’t want to use combination treatment in a low refugia environment. The simplest way to not worry about this issue is to leave a group of animals selectively untreated every time you deworm.

Cummings says cattle producers should always consult with their herd veterinarian to evaluate and customize a deworming program to fit their individual operation.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like