Native range has long got a bum rap because people didn't understand how to manage grassland, but in fact it was and is the ultimate grassland crop.

Kansas NRCS rangeland management specialist Doug Spencer calls native range "the perfect cover crop," which seems fitting in this age when cover cropping is all the rage and is on the tip of so many tongues.

Sadly, there is little true native range left and most of that scattered from Texas to Nebraska, but the lessons it can teach us are useful and much of it could be restored in time.

Spencer lists several assets of native range. It's a list which should make cover croppers exclaim, "Oh if only we had that!"

1. Native range is an efficient water user.

2. It is highly diverse, with dozens or hundreds of species.

3. It has a deep, productive root system.

4. It forms multiple relationships with mycorrhizal fungi.

5. It requires no fertilizer.

6. It reseeds itself or regrows entirely from root stock.

7. It is drought resistant.

8. It is beneficial for wildlife and pollinators.

9. It is safe for grazing.

The diversity is tremendous. On just one ecological type of upland site typical in the Flint Hills, you typically would find about 44 plant species, with 15 grasses, six legumes, 21 forbs, and two shrubs. That data was gathered as part of a process known as the National Resources Inventory (NRI) Rangeland Field Study.

A 2011 research project in Kansas showed cows eat just about everything in the mix. Of approximately 75% of their diet that was grasses, they consumed some of all the species measured June through September. Of the roughly 25% that was forbs or shrubs, they again consumed at least some of everything measured.

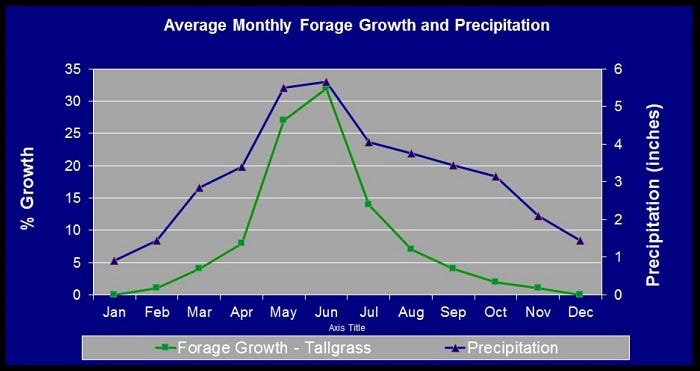

In addition, Spencer says, native range in the Great Plains fits quite nicely with the rainfall pattern, which adds to its water use efficiency. As a perennial plant community, it is nearly always ready to capture and use a rainfall, while annual plants are much more subject to production based on timing of a rainfall.

Interestingly, the proportion of grasses to forbs in healthy native range is a pretty good match with a fairly typical consumption pattern for cattle. Cattle diets can, of course, be altered and improved with high-stock-density grazing and/or weed-consumption training, but it's a definite fit.

Native range was always a soil builder when put in proper cooperation with grazing animals. It still is. Part of the reason for that is it produces great gobs of underground root mass -- roughly a ratio of two-thirds roots to one-third above-ground leaves and stems. Spencer notes the below-ground portion shifts slightly higher in lower-rainfall locations and slightly lower in higher-rainfall areas. This means the native range community of plants is able to shift to higher forage production when rainfall suits it, but the mass of roots and underground life with which it is symbiotic is always great.

Data on rainfall and native range growth from Chase County, Kansas, show a good match, as does native range throughout the Great Plains and beyond.

The key, ultimately, is properly applied grazing. This is even more true for native range than for cover crops, because native range plants must have time to recover from grazing, whereas cover crops are replanted or terminated before cropping.

Spencer says he picked up this analogy from a Missourian: "A cow is a four-wheel-drive manure spreader without steering. That's why you need grazing management."

He adds, "You'd fire somebody who drove your manure spreader or fertilizer spreader around and around the tree out there in your pasture. It’s amazing how precise a producer can be with nutrient placement on the crop field, but right across the fence in the pasture, the herd can be doing the exact opposite and concentrating all the nutrients near shade, water and feed sites."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like