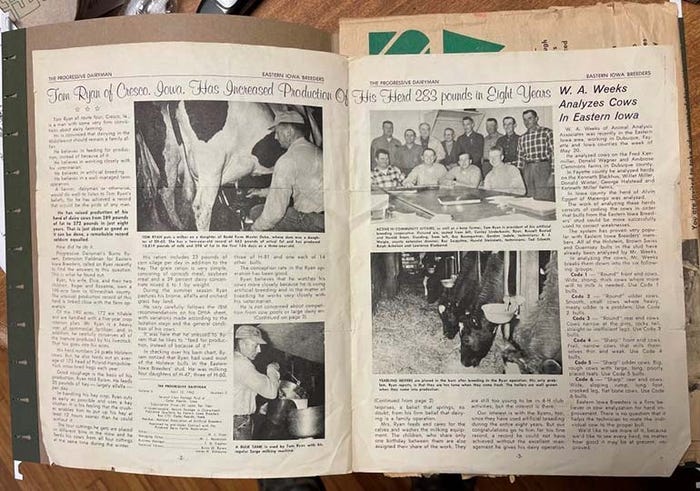

June 7, 2022

Editor’s Note: Jeff Ryan is a long-time blogger for Farm Industry News offering insights, stories and the hijinks of farming in Northeast Iowa. This time out, however, he’s remembering his Dad, or as he always called him – The Chairman. Ryan’s account of a life well lived reminds us all to make the best of what we have.

After a brief illness in late January, we lost my dad at age 91. Tom Ryan had been a farmer almost his entire life, as had his ancestors before him.

My portion of the Ryan family tree came to America from Tipperary in Ireland in 1836 and settled in Illinois. Martin Ryan came to Winneshiek County and filed a claim on 160 acres west of Ridgeway in 1853. At some point, they moved further north toward the state line near the small village of Plymouth Rock. St Agnes Church at Plymouth Rock was built a mile down the road from the village itself.

Dad grew up on a farm west of St Agnes before they moved to a different one east and south of the church. He went to school in a one-room school almost across the road from the public access to Coldwater Creek. We went fishing for trout there when I was a kid. Those trips were also where I picked up most of my official driving experience before drivers ed in school.

Dad would walk out to the pasture each afternoon to retrieve the cows to milk when he was a kid. The pasture was directly above the spot where Coldwater Creek comes out of the bluff and leaves the cave.

Dad could hear voices below one day when he went out to get the cows. He crawled out to the edge of the bluff and could see two guys standing down below. He listened for a while and realized it was a government official talking about the need to protect the area. The actual cave wasn't discovered until sometime in the 1960's.

The curvy road that led from the farm to the school had a deep ditch with a dry creek bed base. The kids would frequently walk through there on their way home from school, because it was cooler and easier walking.

They heard something coming from the north on their way home one day and decided to get out of the creek bed and walk on the road instead. Shortly after they climbed onto the road, a giant wave of water came rushing through the creek from a sudden downpour to the north. Had they stayed in the creek, they would have been washed away.

Another time, as Dad was milking in the barn when they had moved to Ridgeway, Grandpa came in and told him to finish up as soon as he could. They could hear a tremendous hailstorm that sounded like it was near the home place west of Plymouth Rock. Grandpa's youngest brother, Francis, lived up there. He had a huge orchard on the east side of the buildings just off Highway 139. It's a little over ten miles as the crow flies from Francis's farm to the farm northeast of Ridgeway.

Once chores were finished, Dad got to ride along to see what happened. The hail had stripped all the trees bare and wiped out the orchard, which was probably 20 acres. The rain had been so heavy that the hogs in the pasture had been washed over the top of the woven wire fence. They never found a surviving pig from that flash flood in any neighboring fields downstream.

Dad has a sister that is a year older than him. He was the oldest boy, so he started milking cows full-time at age five. The next younger surviving brother was six years younger than him. The one that was two years younger passed away at birth.

Starting out young

Grandpa gave Dad a great deal of responsibility. By the time he was 12, any decisions on which cows to keep or which cows to sell were made by Dad. He had been on the USDA County Committee for years, which meant frequent trips to Decorah for meetings. On those mornings, my older brother and oldest sister did chores. Rather than write down the specific amounts to feed each cow, he told them, "Ask Jeff. He can tell you each one."

I was three at the time and had been peppering him with questions in the barn since I was old enough to ask. The high schoolers were not thrilled with taking orders from a three-year-old who was reciting the background of each cow as they went down the line, hoping they could go to school instead. Dad turned our beef cow herd over to me at age 14, because he felt I was ready, based on what he had seen with the milk cows.

Salesmen who stopped at the farm when he was a kid and ignored Dad and only talked to Grandpa usually didn't make a sale. The ones he remembered and liked the most were the ones who knelt down to talk to him eye to eye and treated him like an adult. Those guys made a sale. We did more business with people who treated me the same way.

Dad used to send me to the sale barn with our order buyer when I was about ten years old. "Jeff knows what we want. He'll tell you when they come through," he told LeRoy as we left in his Buick with his poodle between us.

LeRoy got a couple groups of steers and then passed on one. The ringman came over to him and asked why.

"I'm working for him today," LeRoy said as he pointed at me, "and he didn't want 'em."

The ringman looked at me after that to see if I nodded before he looked at LeRoy for the bid. That sale barn operator got me started on my own a few years later. I think he put his cowboy hat on before he answered the phone if someone called in the middle of the night. He was one of Dad's favorites.

Dad started ninth grade in Ridgeway. He was doing enough on the farm by then that he'd be worn out by the time he got the work done in the morning. He would frequently catch a ride on the running board of a neighbor who was driving to Ridgeway so that he wasn't late for school. He would usually fall asleep on the way into town and fall off the running board. After a couple of near misses getting run over, he decided he had to quit school. He loved playing basketball, but the doctor felt he could hear a heart murmur and wouldn't let him play. With no options for sports as a relief, he decided he had to get the work done at home or it wouldn't get done.

Gaining dairy knowledge

A couple years later, by the time brothers Paul and Phil were old enough to do more, he got a job at the WT Rawleigh Dairy in Freeport, Illinois. WT was a salesman and a showman. He had all kinds of products that he sold, kind of akin to a Watkins salesman. He maintained the dairy farm in order to bring sales trainees to the farm to see how different cleaning products and other things they made actually worked. It also enabled him to sell milk directly to people, thereby opening the door for other products once he had them on the milk bandwagon.

The cows were milked at 3:00 AM and 3:00 PM. That enabled the Sales crew to come to the farm during regular business hours for hands-on training and still get fresh milk delivered before competitors could.

The farm was a showplace. It was meticulously maintained. Herd nutrition was a key, as was cow comfort. If you take care of the cows, the cows will take care of you. Genetics and cow type were paramount. Average cows did not yield top results. You can perform the best with the best. If people weren't coming to the farm for products, they were coming for breeding stock.

Dad put the knowledge he gained at Rawleigh's into his own operation when he started farming. He bought four really good cows. A.I. was the way WT got to where he had, so there wouldn't be a bull. Forage quality had to be good. Nutrition had to be top-notch to get milk production. Cows had to be comfortable. They should never have a bad day.

As my mother used to tell a neighbor, "Sometimes it feels like he takes better care of those cows than he takes care of me."

It didn't take long to get production rolling. A guy showed up every month to take milk samples from each cow to measure production and quality characteristics. In 1961, Dad had the first herd in Winneshiek to break the 500-pound level for annual butterfat production. By the time we quit milking on Thursday, November 4, 1976, our rolling herd average was 18,400 pounds of milk per cow. That was about 40% higher than an average cow at that time. In my A.I. training in 1989, we were told that only five herds in the state of Iowa had a rolling herd average of 20,000 pounds in 1980. We would have been in that group if we had kept milking.

The milk tester would take notes when he was there each month. At one point, he informed Dad that he had been writing down the exact minute when Dad put the milker on each cow each month for several months. It was the exact same minute each time. That is the relentless pursuit of excellence that drove Dad.

"If you take care of your cows, your cows will take care of you."

Answering a military call

Uncle Sam came calling in 1950. He had a rare opportunity for Dad to "travel the world and meet interesting people . . . and kill them." He was drafted into the Army for the Korean War.

He would report to Des Moines for his induction. Once he got there, the plane that was to take them to their next link in the Army chain of adventure had encountered a problem. There would be a delay. It would maybe be a few minutes.

Those few minutes turned into hours. That free time gave him a chance to look around. He met another draftee who was there from Colo in central Iowa. That draftee's name was Earl Schnur, so he lined up alphabetically pretty close to Tom Ryan. Earl had two of his sisters along with him, too. The younger one was named Elsie.

Tom took one look at Elsie and was smitten. Elsie felt the same way. Her older sister, Louise, informed her that that young man from far northern Iowa sure seemed like a catch, so maybe she should get to know him. They exchanged information.

When they finally shipped out for basic training, mail caught up to the young soldier. "Elsie can write a pretty good letter," he quipped years later. The same could be said for him, too.

The two kids stayed in touch from that point forward. Elsie was teaching school in Grand Junction, Iowa and later State Center, Iowa. When Tom was finally discharged, he bought a car and drove to see Elsie. As he pulled into State Center, he met what he was sure was Elsie in her car with some friends heading out of town. He turned around as soon as he safely could and followed them, trying to keep up, but not wanting to risk a ticket, since he wasn't flush with cash after being discharged and spending his money on gas to get there.

Tom finally caught them when they went to the KRNT Theater in Des Moines for a program about an hour away. He pulled up behind Elsie and her friends as they got out of her car. He called her name. She couldn't believe he was there. Elsie tossed her keys to her friends and said, "You're on your own!"

They knew.

The ride of a lifetime started out with a flight delay. One decent fuse, one decent gasket, one cloud bank that cleared sooner and I may not be here. Serendipity is a wonderful thing sometimes.

Marrying a best friend

That friendship led to marriage. That marriage lasted almost 66 years before Mom passed away. Dad was never really the same after that. Losing your best friend will do that.

The friendships you make can make your life. Wilfred lived a mile to our southeast for almost exactly as long as Mom and Dad were here. Wilfred was five days older than Dad. They always got along great and had coffee together as they got older. Wilfred died in 2001. His two boys and grandson that farm got out of dairying 20 years ago but got back in when Nick got out of Iowa State.

They milk cows now and rent some of our hay ground to chop silage for the herd. Whenever I would take Dad out to watch, they'd stop to visit with him, or we'd go down there to watch and visit. Oldest brother Dennis always remembers Dad on his birthday. They all miss Wilfred, so Tommy Ryan has been kind of a substitute for them. (I know where someone knows him from if he's Tom vs Tommy. In Cresco, he's Tom. In Ridgeway, he's always been Tommy.)

Dad would stop to visit with Dennis while he was hauling silage, or he'd ride with Nick in the merger to put windrows together ahead of the chopper, or he'd check in with Craig on the packing tractor at the silage pile. Each time, he would ask questions and tell some stories. He wasn't in a machine, but he was still involved.

I had a request for them a few days ago. It's not a typical question to ask.

"Can you guys help me dig a grave to bury a guy?"

You almost want to ask and look over your shoulder both ways to make sure nobody's, you know, listening, like we're on a "Sopranos" episode.

They didn't hesitate to say yes. "It would be an honor."

We got some shovels and a few five gallon pails and headed out for Plymouth Rock. When we dug Uncle Nip's grave in 2011, it was really dry, so the digging was almost dusty. This one wasn't so bad, but the trees had developed better root systems in the meantime. We had to dig through several of them on the way to 36-inches deep.

Dad was on the Howard County Mutual Insurance board for 30 years or more. Nestor was on the board with him all of those years. They were about the same age. Nestor's son Ray has made my big square bales for years, hauled hay for me and he combined our beans last year. Nestor died in 2018. His funeral was on what would have been his 90th birthday.

When Ray came out the next spring to get a couple semis of big square bales to sell, I had all the bales staged in the yard instead of going back and forth to the shed for them. I told Dad that Ray would probably have some time while I loaded, so he was free to go chat if he wanted to.

Dad was going back in the house when I finished and got out of the skid loader. As soon as I climbed out, Ray said, "I miss my dad. I'm glad I got to talk to Tommy."

When it was time to figure up the custom work bill for 2021, Ray was going to come out to my house. I suggested we go to Dad's instead. Guy Number 1 was there, too. It took about ten minutes or so to figure out the acres, bales and math. The visit lasted almost three hours, and everyone was glad it did. I was sitting where I could look at my phone and sneak a few pictures. I put those together and sent them to Ray when I told him we lost Dad.

Little things can be big sometimes

I sent an email to John Deere Service Manager Mike the day after Dad died. Mike is a year older than me. His grandmother was the third-grade teacher for all four of us in Ridgeway. She did a much better job of teaching cursive than the nuns did. Even the most devout Catholic kids stayed in public school in Ridgeway through third grade.

Mike was an intern at John Deere at Davis Corners (15 miles west of us in flat, boring country, as opposed to the dealership 15 miles east in the hills where they have livestock equipment) in the mid-80's. We had him out once to work on a little square baler, probably because he had 103% of the total experience with hay equipment of the entire staff out there in corn country.

He got the job done about 11:50 and was told to follow us to the house to eat instead of getting back in the truck to eat a baloney sandwich on the drive back west. That's when he became familiar with Elsie and how things work here. He was only a mechanic for maybe ten years before he moved to Service Manager with an office. He will tell you he's never been fed like that in all of those years.

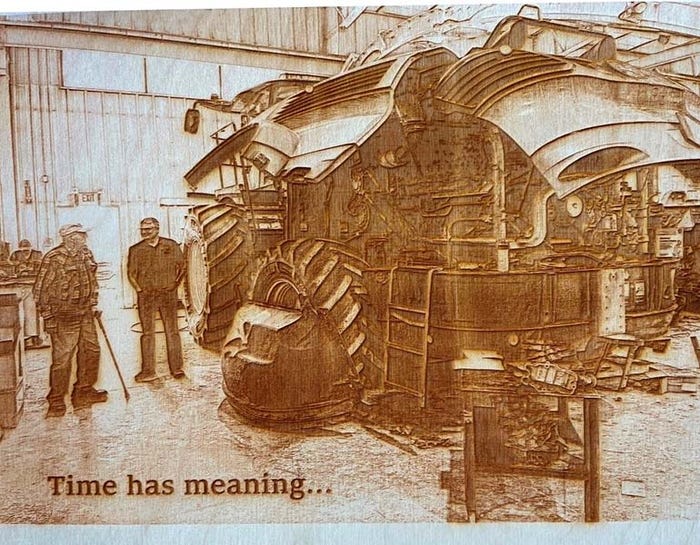

When I stopped to get some parts last spring, I saw a brand new self-propelled chopper sitting in the shop. It was headed to one of our neighbors. I asked Mike later if I could bring Dad in to see it.

"Absolutely! And you make sure you give me a few minutes heads-up, because I want to make sure I'm here to talk to him when you do."

Mike was by the front door when we got there. Dad looked at him when he got out of the car and said, "You need a truck opened up, Mike?"

Mike laughed and looked over at me with a grin. We'd been there years before and were locked out of the truck somehow. No second set of keys and zero patience to wait for some to be delivered from HQ. Dad looked at one of the mechanics and told him to grab him a chunk of wire. A few mechanics gathered by that point to watch. Dad took the wire, put a slight bend to it with his pliers and had the door open in about two seconds.

Most of these guys were my age or older. Radar, a clone of Gary Burghoff, was the one who drove the delivery truck. He lives directly across the road from Coldwater Cave in Dad's old neighborhood. Radar looked at me with his eyes totally bugged out and his eyebrows as high as they'd go.

Paul is the skid loader guy. He had the same look.

Danny is now Honest RC, The Farmer's Friend From Beginning To End, but was the baler and combine mechanic then. Same expression.

Mike was there, too, figuring on calling AAA or the local locksmith in a few minutes after we'd give up.

Dad handed the wire back and we got in the truck to head out, leaving our stunned crowd to walk back to the shop.

When I was back the next time and was in the shop, Radar was there with Mike. "Uh, Jeff, Tommy Ryan has some skills we didn't know about. That was way too easy for him. I think he scared a few guys!"

First job out of the Army

When he got out of the Army, Dad was driving back home and stopped to eat at a little diner on Highway 63 north of the airport intersection in Waterloo. Two guys in Mr. Goodwrench uniforms were at the next table. Dad asked them if they needed a mechanic by any chance. They were from Schukei Chevrolet. Turns out they had stopped to eat and finalize the plan for a newspaper ad placement for a mechanic. They hired him on the spot and told him where to show up. He knew he needed a set of tools, but didn't have a full set or the money to get them.

When he got to the shop the next day, an older mechanic took a liking to him right away and offered to sell him some tools. Between that and what he could borrow, he was all set. It didn't take them long to figure out he had initiative and some skills. The Sales guys then started taking him along on repos. They'd pull up to the deadbeat's house, send Dad out to open the door and take off with it as fast as he could.

"We weren't in the best parts of Waterloo on those calls," was how he put it to me. "I didn't have a lot of time to get it done."

Nothing builds a skill set like the chance of a bullet coming at you as you're trying to get the door unlocked. That skill set remained intact 60 years later at Deere. I had never seen it used, but I'd heard stories about it. That was the day that Mike took his respect to a whole new level.

Mike called me after he found out we lost Dad earlier this year. He hadn't realized how much he meant to him, which went both ways. You do business with a lot of people. Some of them do the minimum. Some do even less, but the good ones go above and beyond. Those people become friends.

A friend from Twitter can take photos and engrave them into wood. I sent him the photo of Dad and Mike by the chopper from last year. Mike has since been promoted to supervising and advising the service managers at all the dealership's stores. My thought was to put something together to remind him of what it means to do more than just the minimum at your job.

Preview to a funeral

In an unusual way, Dad kind of got a preview of what his funeral visitation will be like. We nominated him for the Iowa Master Farmer Award in late 1999. Applicants were encouraged to submit letters of support from neighbors, fellow farmers, businesspeople and anyone else who knew the applicant.

Another friend whose Dad had won in the past after two attempts told me that you can't send too many letters of support. We read through a pile of letters when Roxann and I stopped, looked at one another and decided it was eerily like standing in line at the funeral home at some point in the distant future as we listened to each person recount their time with Dad. We were kind of glad he got to see it in person ahead of time.

When we were done with Elsie's funeral, Dad and I talked about how it went. He genuinely liked the buggy ride for her to the cemetery. I asked if he wanted me to do the same for him if he went before I did. Without hesitating, he said he did. That's when I knew he was serious. If there had been any question, he would have paused or hedged. I could see his eyes brighten, so I knew he meant it. I told him I would gladly do it, but it would be much easier in, say, June vs January.

"I'm going to be cremated. Lee can put me on a shelf for a while until the weather's better."

That is a practical farmer. Don't rush it. Wait for good weather.

Robert Ryan is the caretaker of the cemetery at St Agnes at Plymouth Rock and a third-cousin of mine. Robert always has the graves decorated with flowers and flags from mid-May to mid-June. That was Dad's favorite time to go there.

We went with Friday June 3rd for the service to hit the middle of that window. The GuyNo2Mobile was detailed. The grave was dug. The friends and family were assembled. We had perfect weather for the day. It was sunny and 70 degrees.

As we prepared to leave the funeral home, several people reminded me "Don't forget Tom!"

We didn't want this to become a tradition where I had to make a mad rush to get from Plymouth Rock back to Cresco to retrieve the celebrant while the crowd waited patiently at the gravesite.

This procession was a bit more organized than Nip's was. Lee, the funeral director, had asked if I wanted him to drive in the far driveway at the church. That would get everyone into the fairly narrow path without clogging it with car doors opening up as the rest tried to get by.

Lee had moved up to Temple Grandin status in my book at that point.

My sister had mentioned something about the urn earlier in the week - whether it had a solid lid on it or not. Both Mom and Nip had been placed in sturdy boxes. When I heard the term urn, I was immediately thinking about a jar with a lid. That took me to the big hill right before the cemetery, and how I'd probably come over that hill and a big gust of wind would blow the lid off the urn, scattering Dad in a cloud less than a mile from his final destination. I would show up at the cemetery looking like Al Jolson, trying to act like nothing happened. It would be Mel Brooks' version of Weekend at Bernie's.

This may be a duct tape mission.

Fortunately, the container was a solid box and not a cookie jar. Sure, I could still screw it up, but it seemed less likely.

Mostly.

The last day

I pulled up behind the hearse in the yellow buggy at the cemetery without having to leave the standard 12-foot casket and pallbearer buffer zone. Lee then asked if I wanted to take Tom to the grave myself or have the soldiers do it.

This was a new wrinkle I hadn't considered. Two soldiers were nearby in their dress uniforms. They did not look like the usual American Legion crew from Cresco. I decided to turn it over to the professionals.

These two soldiers were from the State Honor Guard. One of them took the ashes from me and, with complete military precision, turned and placed them in the back of the hearse, accompanied by a folded American flag. Much like the changing of the guard at Arlington National Cemetery, the two soldiers proceeded to take the ashes to the grave and then unfolded the flag, refolded it and presented it to me on behalf of a grateful nation for my father's service.

The American Legion then did a 21-gun salute. A young man then played Taps on his trumpet. Dad would always cringe when they would use a cassette on an old Kraco boom box. He never asked for it, but I made sure that Taps would be live and in person for him.

If you follow me on Twitter @GuyNo2 you will find a few of the videos from that day.

We did not return to the church for a meal after the burial. Dad always said, "You have two options for a church dinner. Scalloped potatoes and ham, or ham and scalloped potatoes."

He considered that to be a 0-for-2 option.

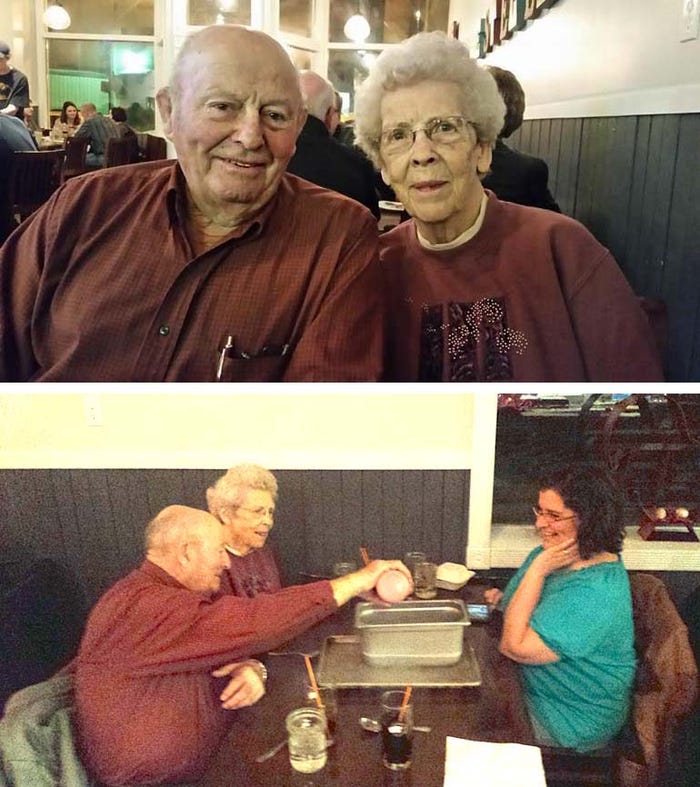

Some of the best pictures we have of my folks in their later years were taken while we were dining at Estelle's in nearby Harmony, Minnesota.

I talked to Chef Matt and got a plan together. When we finished at the cemetery, we would head a few miles up the highway to Harmony. The patio would be reserved for us with a buffet of pulled pork, pork nuggets, smoked Gouda mac n cheese, coleslaw, dinner rolls and bread pudding.

It touched all the bases that both Mom and Dad loved. Okay, we didn't do Moon Rocks like we did in the photo above, but you have to draw the solemnity line somewhere.

I got the grave filled and then headed to Harmony to eat and visit with friends.

It felt like a good way to celebrate a life well-lived. Gather with friends, look back, remember, share stories and laugh. Then move forward from there.

There is more to learn.

Get busy and get it done.

Satisfaction starves progress.

Take some time to enjoy it.

Thanks for the lessons, Dad.

With no further business, The Chairman moves to adjourn this life.

Guy No. 2

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like