Applying anhydrous ammonia in the fall is a balancing act, says Peter Scharf, University of Missouri Extension nutrient management specialist. “The longer you wait, the less risk of losing the [nitrogen] before your corn needs it,” he says, “but the greater the risk of running short of field time.”

Scharf warns farmers not to head to the field to apply fall fertilizer right when soil temperatures at 6 inches hit 50 degrees F.

“The most dangerous thing about this guideline is that some people interpret it to mean that it's 'safe' to apply anhydrous once soil temperature falls to 50,” he explains in a recent MU Integrated Pest Management newsletter. “That's way too simple. Waiting until after 50 reduces the risk, but not by a lot. The later you wait, the lower the risk that the N will be lost before the corn needs it.”

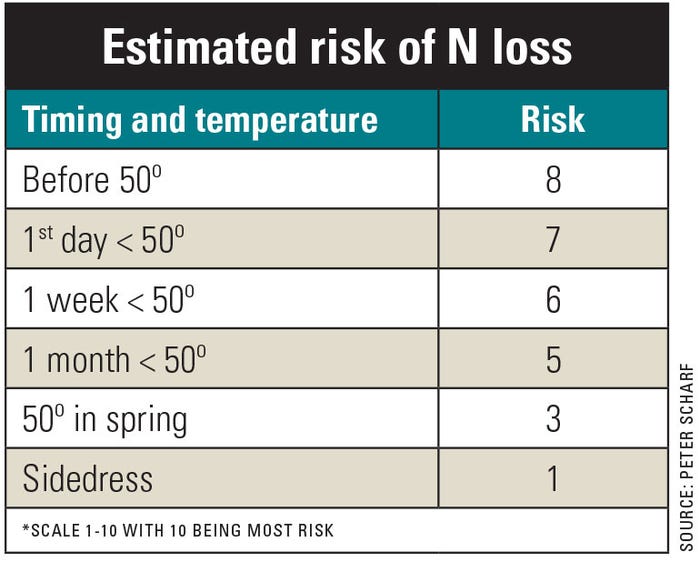

So, Scharf created a simple risk scale to offer farmers a comfort level based on temperature for applying anhydrous. The scale is from 1 to 10, with 10 being the greatest risk of losing nitrogen before plant uptake.

Scharf explains that ammonia still converts to nitrate at 50 degrees. It's slow, he adds, but once the ground is frozen, it stops. “We have a lot of years where it never freezes at anhydrous depth,” he adds.

He offers farmers guidelines for fall nitrogen application in corn:

Watch the weather. Pencil in an 8-bushel loss if weather is average, Scharf says. A three-year study covering 50 farm fields where fall anhydrous was applied showed that in a year with average precipitation from November through March, there was an average yield increase of 8 bushels by sidedressing N.

Scharf says this showed that N loss was holding the crop back. He contends that adding extra N in the fall could make up some or all this yield gap in a year with average rainfall.

However, Scharf found that when precipitation during the exact time frame was less than half the average, the anhydrous remained in the soil. But it would be wasted money in a dry year and would not provide nearly enough N in a wet year with high N loss, he adds.

“There is a much wider range of possible outcomes, more uncertainty, with anhydrous applied in the fall than applied in the spring,” he says.

Make a weather plan. Both warm and wet conditions contribute to nitrogen loss, Scharf says. Farmers should have a wet weather plan to avoid losses. Even if a field receives a nitrogen application at the right temperature, under the right weather conditions in the fall, spring rains can affect nitrogen levels in the field.

Scharf points to a field that did everything right, but rains came in the spring. The result was a variable yield across the fields, where some spots saw a 45-bushel loss. “This field is well-drained, so the excess rain did not hurt the corn directly,” he says. “It hurt it by taking away its nitrogen.”

Scharf completed on-farm tests in four states over six years where there was excess spring rain. “Yield response to extra N was highly profitable except in one state in one year,” he says. “And the worse the corn looks, the more it responds."

Apply full rate. Scharf says it is probably better to apply a full rate on a limited number of fields than a limited rate on all fields. “Either way, you're not putting all your eggs in one basket,” he explains. “You're limiting your risk as far as N that is lost. But if you put a full rate on a limited number of fields, and have weather that doesn't cause any loss, you don't have to go back.”

He adds that fall nitrogen application typically costs less, but average loss for fall N eats away at the cost savings. “And it adds uncertainty,” he says. “Did you lose N, or didn't you? This is a much harder question to answer when you put your N down on Nov. 2 than when you put it down on June 2.”

The University Missouri Extension contributed to this article.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like