February 13, 2024

Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series about one-room schools. In last month’s story, Jerry Apps recalled the history of Wisconsin one-room country schools and shared some stories.

Anyone who attended a Wisconsin one-room school likely has favorite memories of special events such as the Christmas program and end-of-year picnic.

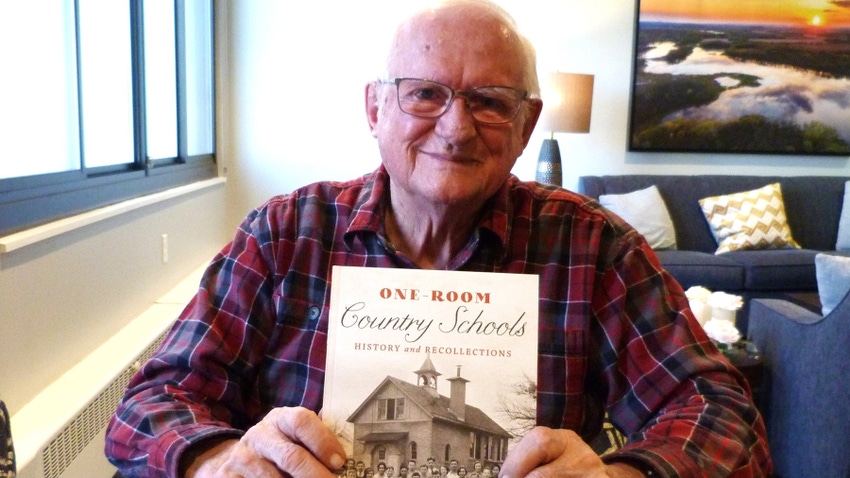

Among those with fond memories is Jerry Apps, the noted Wisconsin historian who attended a one-room school in Waushara County, Wis., from first through eighth grade. Apps has written 45 nonfiction books and 10 novels during the past 54 years, and one of them — “One-Room Country Schools: History and Recollections” — chronicles the storied history of country schools from about the time Wisconsin became a state in 1848 to when most of the schools fell victim to consolidation in the 1950s and 1960s.

Rural diversity

Apps, 89, attended the Chain-O-Lake School near Wild Rose, beginning when he was barely 5. He says he learned a great deal during his eight years at the school, but perhaps the most important thing was how to get along with others.

“An interesting characteristic of our neighborhood was that we had German, English, Polish and Norwegian kids, you name it,” he says. “The Polish and Norwegians were first-generation immigrants, and they spoke their home language. Can you imagine a teacher facing a little kid who doesn’t know how to speak English when she has 25 other kids in the classroom?”

Some of the children in his neighborhood were so poor that they would come to school with big holes in their shirts and pants, and very little in their lunchboxes.

“I remember this one little kid who had two thin slices of bread spread with lard, and that was it,” Apps says. “So, you learned how to share. Once we saw that, Joe would say, ‘Here, I’ve got an extra cookie,’ and Susan might say, ‘I’ve got a sandwich here you might like.’ That happened every day.

“To learn how to share and get along with all of these different kids from first to eighth grade was very important. We pretty much knew we had to learn to get along with everyone or we weren’t going to make it. That’s what community was all about.”

MEADOWVALE SCHOOL: The Meadowvale School sits north of Barneveld, Wis., on County Road K, and is now owned by Logan Rue. (Karin Rue)

Christmas program

The Christmas program was a highlight of the school-year calendar at all country schools. Apps has distinct memories of two of his Christmas programs. When he was in first grade, his teacher, Miss Piechowski, assigned him the duty of welcoming everyone to the event. He told his teacher and his mother that he didn’t want to do it, but they both said he didn’t have a choice.

“The night of the program I was fussing and fuming, and Miss Piechowski says, ‘Jerry, let me tell you a secret. When you get up on stage, I want you to use your outside voice, and I want you to look at the damper on the stove pipe in the back of the room. Don’t look at the people – if you do that, you won’t be able to remember your name.’ I’ve been looking at that damper for 80 years.”

His entire speech was: “I’d like to welcome all of you to our annual Christmas program.”

Fast-forward to fifth grade, when a mouse crawled out of the piano while the teacher was playing “Away in a Manger.”

“She had told us when the baby Jesus was in the straw, this was a solemn event, and she didn’t want to see any giggling or smiling,” Apps recalls. “The teacher didn’t see the mouse right away, but everybody else in the school did. A couple members of the school board finally came up and shooed the mouse outside. Those are the kinds of things you remember.”

STONEFIELD VILLAGE SCHOOL: A one-room school building greets visitors at Stonefield Village and Agriculture Museum in Cassville, Wis. (Susan Apps-Bodily)

WHA Radio

At 11 a.m. each day, the teacher turned on the school’s battery-operated radio so all the students could listen to WHA Radio and “Wisconsin School of the Air.” The program covered subjects ranging from government and history to music, art, literature, nature, health and safety. “Journey in Musicland,” hosted by Edgar Gordon, and “Afield With Ranger Mac” were among Apps’ favorite features.

“People criticized the country schools for being so isolated, but the ‘School of the Air’ tied together literally thousands of country kids for many years,” Apps says.

Each country school had its own school board, which was elected by the residents in the district. At the time when one-room schools flourished, the school boards were the lowest form of government, followed by the town, county and then state government.

RADIO SHOW: Students listened to “Wisconsin School of the Air” in many country schools for decades. (UW-Madison Archives)

School board members determined school expenditures, hired and fired teachers, and made sure the school was properly maintained. Generally, school board members had children attending the school, so they knew what was happening from day to day.

Apps says his father was the school board treasurer, although his mother did most of the bookkeeping for the school. He recalls that the teacher made about $35 a month, and many of them roomed with families in the school district.

Each county also had a superintendent of schools, and he or she was responsible for all the country schools in the county. Eighth graders were required to take a test at the county seat near the end of the school year to determine if they were ready to attend the local high school.

“In those days, eighth grade graduation was considered an achievement of first order,” Apps explains. “Graduating from high school was probably a good idea, and college — how do you spell that?”

Some country school teachers weren’t much older than some of their students, with the only requirement being a high school course or two on country school teaching, Apps says. Later the model was changed to require two years in a normal school to teach in a country school, and after consolidation, teachers had to have a four-year degree.

School picnic

The end-of-year picnic was an event that everyone looked forward to, Apps recalls.

“Everybody brought something for a potluck, and at our school, the school board was responsible for bringing the ice cream,” he says. “The ice cream came in 2½-gallon metal containers that were encased in canvas to keep the ice cream from melting.”

The dads played softball with the kids during the picnic, which Apps says was a special treat.

“This was the first time I remember seeing my dad play anything. He seemed to be working all the time, and when he wasn’t working, he was napping,” Apps says.

MEADOW GROVE SCHOOL: The Meadow Grove School off Prairie Grove Road south of Barneveld, Wis., was built in 1924 and is now the home of Peter Kettler. (Ken Rue)

School consolidation

When Apps was a senior in college in 1955, he attended a meeting for the Chain-O-Lake School District to discuss the closing of the school. A researcher from the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education was extolling the virtues of consolidated schools — better art, math, reading and physical education — when an elderly gentleman asked what an enhanced physical education program might be all about.

“I’m so glad you asked,” the researcher said. “We have all of these games for kids to play. We have ropes to climb, hurdles to jump over — it’s all organized, and your kids will benefit from it.”

Apps recalls the old man saying, “Wait a minute, let me tell you a little bit about what my kids have to do during the day. They are up at 5:30, out in the barn helping me with the milking. Then after they come in for breakfast, they walk a mile and a half to school, and after school, they walk home, and they’re in the barn helping with the afternoon chores. After supper, they help with the milking, and then they fall into bed and do the same thing the next day. I don’t think they need any more physical education.”

Despite arguments against consolidation, as the number of farms and family size decreased, most one-room schools closed in the 1960s, bringing together students from several country schools to join the children in town.

“The values that came out of one-room schools could still be taught today — helping each other learn, the notion of developing a community and realizing that you are responsible for your own learning,” Apps says. “We are all part of something much bigger, and we should learn how to cooperate and share things with each other and learn how to learn by ourselves.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like