It’s been over a year and a half since bacterial leaf streak, a bacterial disease known for infecting sugarcane fields in South Africa, was first discovered in the U.S. in Nebraska cornfields. In that time, it’s been confirmed in eight other states, including surrounding Iowa, Colorado, Kansas and South Dakota, as well as 60 counties here in Nebraska.

However, much of the initial concern has died down, says Tamra Jackson-Ziems, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension plant pathologist.

“Part of that is because in many places, it seems like there was less incidence of bacterial leaf streak this year than we’ve had in the past,” Jackson-Ziems says. “Second, I think having a name to put to it, and knowing what it is has helped alleviate a lot of the alarm associated with it.”

While the disease showed up for a second time in 2017 — and in some new counties, including in the Panhandle — the level of severity, especially in these drier areas, has not been as high as 2016.

After a year and a half of research with this new disease, Jackson-Ziems notes there are some key findings in regards to BLS’ host range.

New hosts identified

UNL graduate student Terra Hartman has conducted a study supported by the Nebraska Corn Board over the 2016 and 2017 growing seasons that identified new hosts for the disease.

Hartman explains the research involved inoculating 34 different plant species with Xanthomonas vasicola pv. vasculorum, the causal agent of bacterial leaf streak, in an inoculation chamber. After leaving the plants in the chamber overnight, she notes several species showed symptoms — including some surprises.

“We found that oats and rice both showed symptoms, also big bluestem, little bluestem, indiangrass, orchardgrass and timothy. Also bristly foxtail, green foxtail and yellow nut sedge showed symptoms,” she says. “That was kind of surprising; it showed what a wide range this bacteria had.”

Of course, a greenhouse environment is much more conducive to disease development. These species were also tested in a field near infected corn, and both big bluestem and bristly foxtail were found susceptible in this environment.

“Oats are sometimes planted as a cover crop in Nebraska, and if it’s in a cover crop rotation with corn, the oats can act as a host for the bacteria when corn isn’t growing in the field, which provides a continued source of inoculum and a place to survive over winter,” Hartman adds. “With weeds like bristly and green foxtail, it’s an issue of weed control. If someone isn’t controlling their weeds when rotating to soybeans, the weeds can also act as a host while the corn isn’t in the field. If the bacteria happened to infect pasture grasses, and someone baled it, it could potentially be spread across the state or into other states.”

“Big bluestem is one of our common prairie grasses that we bale, feed and move around,” Jackson-Ziems says. “To me, that’s alarming because, big bluestem, little bluestem and indiangrass, being perennial and native here, they could serve as a reservoir for the bacteria. It’s unclear at this point how susceptible they are. Could they inoculate a cornfield and spread the disease?”

Research ongoing

UNL also began studying potential practices to mitigate bacterial leaf streak at three locations across the state this year with funding from a USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) farm bill grant, including different crop rotations and tillage strategies.

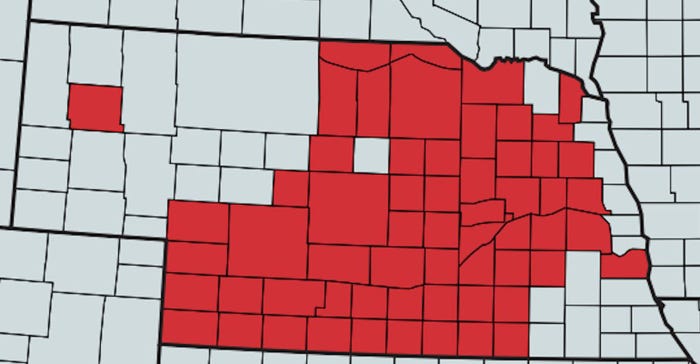

BLS IN NEBRASKA: While bacterial leaf streak has been confirmed in 60 counties in Nebraska, plant pathologist Tamra Jackson-Ziems says the severity varies from different parts of the state.

UNL is also working with Colorado State University and Iowa State University to research how the disease overwinters on crop residue. This includes six locations in Nebraska with bags of infected residue buried 4 to 6 inches below the surface. These bags will be collected in April to determine how well the disease overwinters in different conditions.

In addition, Iowa State University is leading a seed transmission study, and UNL has been submitting grain samples for ISU’s Seed Laboratory to test over the last two years to determine whether the bacteria can be transmitted via seed.

UNL is working with USDA’s Plant Introduction Station in Ames, Iowa, to evaluate publicly available corn germplasm lines for susceptibility to the disease.

“I was very pleased we saw a wide range of reactions to the disease. Some were susceptible, and some were quite resistant. That gives us hope that there is resistance out there,” Jackson-Ziems says. “Someday we’ll have commercially available hybrids that will be resistant to the disease. In the end, I think that will be the most effective way to manage it.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like