The snow has melted away across most areas of the Northeast, allowing for winter wheat to start waking up from its dormancy. But with such a cold, snowy winter, some of that wheat may have come down with snow mold. And if enough of it is out there, now this is the time to be on the lookout and possibly switch to another spring crop.

Snow mold is caused by various pathogens that, under the right conditions in late fall and winter, can spread in fields, according to Alyssa Collins, Penn State plant pathologist.

“In all cases, the occurrence of snow molds was favored by an early snowfall, which was then followed by a deep snow on unfrozen ground. When this occurs, the microenvironment is very favorable for fungal growth on the plants throughout the winter months,” Collins wrote in an online field crops article. “Scouting for snow molds often focuses on targeting areas of the field where snow cover was greatest.”

According to the Crop Protection Network, a multistate partnership of university and provincial Extension specialists, signs of snow mold vary depending on the pathogen that’s present. Some plants will appear pink or have a fuzzy growth on some of the dead or dying leaves. Others will leave behind a more gray-white fungal growth that eventually turns dark and causes infected tissue to look speckled. A snow rot will appear as dark-green blotches on leaves of plants in low-lying areas with cold water accumulation.

Collins says she’s been getting a lot of inquiries from area farmers about possible snow mold in the past week or so. The bad news is that there isn’t much to do about it in terms of a chemical control that will kill the pathogen. The good news is that there’s still time to decide whether to keep the field in wheat or rotate into corn or soybeans.

Count your stand

Doing a wheat stand count can be a good place to start. If you have a yardstick or a dowel rod that’s at least 3 feet long, and your field hasn’t greened up, count whole plants, not tillers, says Del Voight, Extension agronomist with Penn State. Then follow these steps:

Place the measuring stick next to an average-looking row and count all plants in the 3-foot length of the row. Record that number.

Repeat the counting process in at least five other locations well-spaced around the field.

Average all the stand counts from the field.

Calculate plants per square foot with the following equation: (average plant count × 4)/row width in inches.

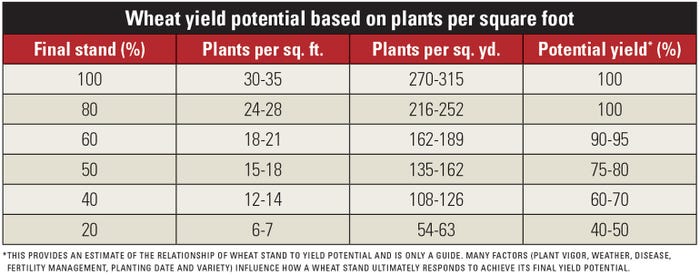

If you come up with under 15 plants per square foot, that’s less than 75% yield potential, and the field probably should be rotated into corn or soybeans, he says.

If the stand is “adequate,” you may consider an early nitrogen application.

Check out the table below as a guide.

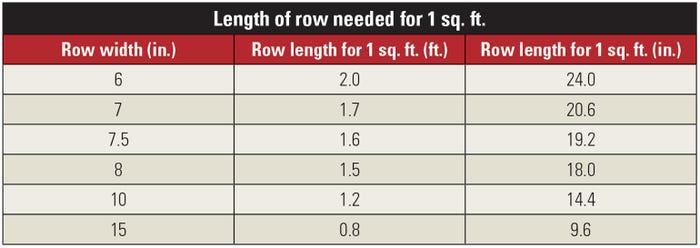

A variation is to determine the length of row needed to equal 1 square foot. Mark the needed length on a dowel rod or stick, and then count the plants in a row. Use this table as a guide.

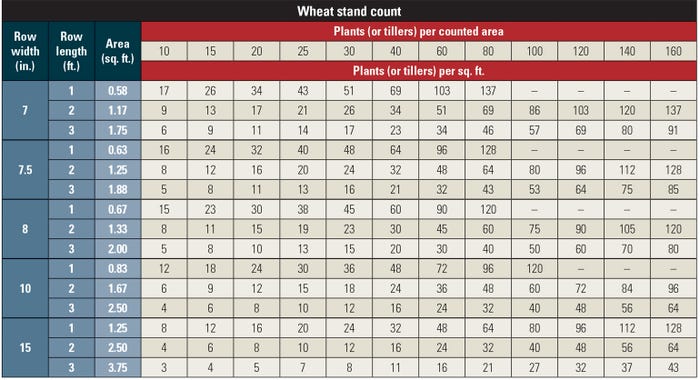

Another option involves counting the plants, or tillers, in 1-, 2- or 3-foot-long rows and using the table below as a guide. This was developed by University of Kentucky Extension.

If you have enough plants, count the tillers to determine amount of nitrogen that might be needed. To determine tillers, count all stems with three or more leaves. If tiller counts are below 70 per square foot, you may need to apply nitrogen starting at the Feekes 3 growth stage.

Since wheat plants are young, Voight says to take extra care with nitrogen application to make sure you don’t burn the plant.

“One pound of N per bushel is the key to ensuring adequate yields. If your goal is 80 bushels per acre, you will need to supply 80 pounds of N to achieve that yield goal,” he writes.

Prepping for next time

Collins writes that rotating into a legume may help to lessen the amount of snow mold fungus in the ground, but it won’t remedy future problems completely.

Checking the small grain cultivar for snow mold resistance could be an option for future years.

Fall planting is another factor to consider. If you have the chance to plant early, you should, she says, because larger plants are more resistant to infection and can resume growth the next spring.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like